By James K. Galbraith

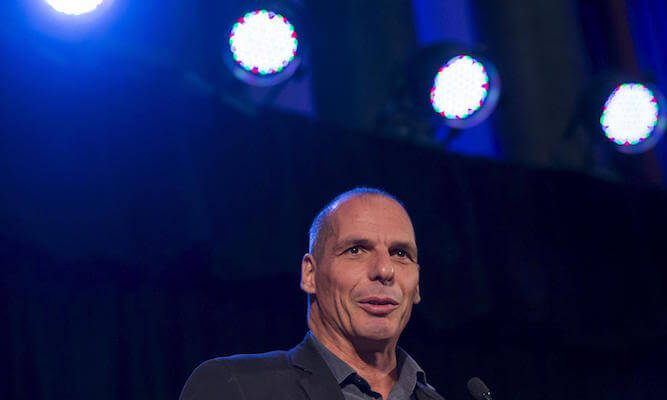

My family connections to Greece go back to the friendship between my father and Andreas Papandreou, colleagues as economics professors in the United States in the 1950s. In 2010 I arrived in Athens to lend moral support at a difficult moment to George Papandreou, then newly-elected. I met Yanis Varoufakis in 2011 and helped to arrange his two-year sojourn at The University of Texas at Austin, beginning in 2013. During that time, as well, I made friendly contact with Alexis Tsipras and members of his circle. These connections and a deepening concern with the effect of the Greek tragedy on Europe and the world led to my engagement – as a volunteer and friend – with the Finance Ministry from early February until early July, 2015.

We knew from the start that the incoming Syriza government faced a most difficult challenge, to persuade intransigent institutions, hostile finance ministers and wary heads-of-state to modify a failed economic program, which had been imposed in the first place not to assist the Greek economy but in order to save the French and German banks. The mission of the finance ministry was therefore diplomatic and political, and my role, mainly, was to help by writing and speaking in public, to the international press, and to keep friends and sympathizers in the United States and elsewhere informed.

Welcome to the Poisoned Chalice (Yale, 2016) is a collection of my writings, interviews and speeches on Greece from 2010 through the summer of 2015. Most of them were published at the time. Together they convey the flavour of the early SYRIZA months as I experienced them, along with my judgments about the economics and politics of the situation.

As the book relates, in March 2015 Yanis Varoufakis asked if I would help with a delicate task. This was the preparation of a preliminary plan – requested by the Prime Minister – for the contingency that Greece might be forced out of the euro. We all knew that events would build toward a climax at the end of June. We did not know – and could not know – what specific form that climax might take. It was necessary to prepare for the worst. Together with a small group I worked for about six weeks on this plan, and submitted a memorandum – the “Plan X memorandum” – in the first days of May.

Our work drew on the financial and legal expertise of our team, on the academic literature on currency transitions, on a small number of private conversations with trusted experts, and on our own knowledge of the Greek economic and social situation. We hoped to provide an outline of measures that might have to be taken and of problems that would occur. We were acutely aware of the difficulties that Greece would face if it were forced to leave the euro, and also of the dangers that would follow if our work became known. For these reasons, we worked quietly, mostly away from Athens. The larger Greek government – outside or even within the finance ministry – was not involved.

The issues surrounding a forced exit from the euro were daunting: they ranged from the legal relationship with the European Union, to the creation and management of a new central bank and the mechanics of providing reliable liquidity on short notice, to possible external support for the new currency, to the transformation of bank deposits and private debts, to such essentials as maintaining supplies of essentials including food, fuel and medicines. We could not know how Greek political and social forces would react. Our job was to assess these considerations to the extent we could – an extent that was often very limited. It was not our mission to make recommendations, and we made none; we were preparing for a scenario that everyone hoped to avoid.

At the end of the day, Yanis Varoufakis, the Finance Minister, discussed our work with the Prime Minister, and the Prime Minister made his decision, as everyone knows. That was the Prime Minister’s judgment to make. I left Greece on July 7, 2015, with mixed emotions. On one side, I had wished for a better result for the Greek people, for a stronger boost from Greece’s friends, for a bit of flexibility from the creditors, which never appeared. On the other side, I felt content in having rendered service in a good cause. And in the confident judgment that my friend, the finance minister, Yanis Varoufakis, had carried out his responsibilities with distinction.

James K. Galbraith holds the Lloyd M. Bentsen Jr. Chair in Government/Business Relations and a professorship of Government at the Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs, The University of Texas at Austin. His new books are Inequality: What Everyone Needs to Know (Oxford, March), and Welcome to the Poisoned Chalice: The Destruction of Greece and the Future of Europe (Yale, June).