By Sean Whelan

14 Mar 2020

They say timing is the essence of comedy. It may also be the key to understanding why different countries are taking different approaches to managing the coronavirus outbreak.

This of course is no laughing matter, especially for people living on an island that is taking two different paths to the same objective.

The stark difference between the British and Irish approaches has unsettled many in Ireland. But many questions have also been asked in Britain too, with some signs on Friday night that the government’s position was shifting.

Earlier in the day, scientists advising the British government were being put out on the kind of media rounds that normally await ministers.

And they face the same questions, no matter where they appear: Why is the British approach so different to what is going on in other European countries, where school and college closures, bans on big sports events or other public gatherings, transport restrictions and even border closures are becoming the norm?

The answer boils down to timing.

The UK scientific and medical advisers do not expect the infection rate to peak for another three months.

They believe that it is too early to take drastic measures, and that if they are taken now, they will have to be held in place longer than most people expect, and because of that they would lose effectiveness just when they were most needed, because people would get bored and stop practising the hard disciplines of “social distancing”.

So to be a little more precise, it is timing, and what people will put up with. The view of government advisers, scientists, medical experts and behavioural economists, is that asking the public to do too much at the wrong time will make the problem worse.

Right now, the British government believes that the biggest impact it can make in terms of slowing the spread of the disease is to request that anyone with a persistent cough or fever should self-isolate for seven days, which is the main infectious period, and not bother contacting a GP or even the phone helpline.

This, they say, will be more useful in slowing the disease than any other single measure, saying it could reduce the rate of spread by 20%-25%.

The government also plans to roll out, in a phased way, social distancing measures for the elderly and other vulnerable groups when it judges such moves will have their biggest impact in dealing with the problem.

And what is the problem?

It is that the normal course of the virus to spread slowly at first, then go into a very rapid exponential growth phase, hit a peak, and then collapse back down almost as quickly.

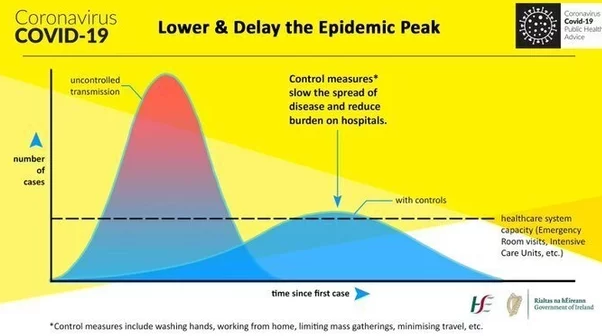

Boris Johnson, in his inimitable way, described the resulting chart (or curve, as economists like to say) as looking like a sombrero. And he said the aim of public policy is to “squash the sombrero”.

In other words, to flatten and elongate the curve, so that the peak point of the virus in society does not to produce more seriously ill people than the health service can cope with at any given time.

If the virus is allowed to run its normal course, this peak arrives very rapidly, with a huge number of infections happening in a couple of weeks. A certain percentage of them will need hospital treatment for respiratory conditions.

But there are only a fixed number of hospital beds, ventilators etc and medical staff to attend to them. If the capacity of the medical system to treat people is fixed, and the percentage of people infected with Covid-19 who need hospital treatment is also fixed, then the variable element is the rate of infection in society. And it is this variable figure that governments are trying to control.

The aim is to slow the spread of the virus over a longer time period, so that the number of cases requiring hospital treatment doesn’t all arrive at once.

This is the same target that all governments in Europe have: they are all using the same charts, showing the same pattern of a steep, narrow peak, bursting through a line representing the capacity of the health service, followed by a gently rising and falling hillock, that is supposed to represent a longer, slower rate of coronavirus infection, one that doesn’t overwhelm the health service.

Nobody is saying they can stop the virus.

Delay is the watchword for all European governments now, including here in the UK.

But Britain is not closing schools and colleges, as Ireland, Denmark, Belgium France, Spain, Portugal, Germany and others have done in the past few days.

Nor are they minded to ban sports events or large cultural gatherings, as has been done in Ireland and a few other countries. In Belgium, they are shutting bars, cafes and restaurants from Monday. Brussels is a two-hour train ride from London, quicker to get to than Manchester.

Yet it is the Irish example that has got a lot of attention in Britain, possibly because it looks and sounds a lot more like Britain, possibly because it’s not “over there” on mainland Europe, but is to the west of Britain, almost implying the situation has leapfrogged Britain, and it is somehow behind the curve in its response.

On Thursday morning, before the UK government’s latest advice to the population was released, the editor in chief of the prestigious medical journal “The Lancet”, Richard Horton, accused the government of “playing roulette with the public”.

He said the government was not, as they said they were, acting on the science. “The evidence is clear: we need urgent implementation of social distancing and closure policies,” he said.

Another critic was the former foreign secretary Jeremy Hunt (who was the challenger to Boris Johnson in last year’s Tory leadership contest).

He criticised the government after its announcement for not banning large gatherings, describing it as “surprising and concerning”, particularly if the country has “four weeks before we get to the stage that Italy is at”, leading him to conclude that “you would have thought that every single thing we do in that four weeks would be designed to slow the spread of people catching the virus”.

Herd immunity making people uneasy

There is also unease that the concept of herd immunity. This is the idea that a population builds immunity to the worst effects of a new disease when most of the population has been exposed to it.

It’s the theory behind vaccination. But because there is no vaccine as yet for the Covid-19 virus, the only way to build herd immunity is for people to catch Covid-19.

In most cases people get over it pretty easily (though it’s not known if it will become a recurring annual disease).

Some have accused the government of being willing to sacrifice large numbers of people to the virus in order to build up a level of resistance in the general population.

According the theory, herd immunity is reached when about 60% of the population has been exposed to the virus.

People run the numbers, based on the currently known death rate, and estimate 200,000 people could die before herd immunity is reached.

K government scientists deny this, saying the tactic is delay, so that people who need hospital treatment can get it, as the system will not be overwhelmed.

When asked point blank if herd immunity is the governments objective, they deny it. But they also say achieving herd immunity is the only way to defeat the virus.

Speaking beside the prime minster at the Downing Street briefing on Thursday, the Chief Scientific Advisor to the Government Sir Patrick Vallance said it was “not possible to stop everyone getting the virus, and it is also not desirable because we need to have some immunity to protect ourselves in the future”.

In a Channel 4 news special programme on the virus shown on Friday night, Professor John Edwards, of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, who also advises the British government, said there are two ways to deal with this virus.

Either stamp it out by curing every person in the whole world who is infected, which we are no longer able to do, or managing the spread of the virus until herd immunity is reached. When challenged about a potentially large death toll, he said “there is no way out of this”.

Two issues were key for him. The timing and the timescale. It’s going to take months, if not the rest of the year to get a grip on this, not a matter of weeks. Secondly, what will people put up with for those months? There is no point in asking people to do something for a few weeks that they should really do for a few months.

Professor Edwards was also very doubtful about the effectiveness of a social lockdown for a few weeks.

What, he asked, happens when the lockdown is relaxed? The virus will come back and the risk of a sudden, overwhelming peak rises again.

Hence the preference of the British government for a strategy that drags the infection rate out over a long period of time, whilst accepting the inevitability of mass infection as an apparently desirable outcome.

Will the UK shut down schools?

Shutting schools appears to be an unspoken case in point: the implication of what the British are saying is that shutting down schools for a couple of weeks won’t achieve the effects needed. It will be more like a four-month shutdown.

That has all kinds of other problems going along with it. What to do with the children, those that need constant minding will require parents to drop out of the workforce, which is particularly difficult for health sector workers. Or worse still, children may get sent to grandparents for minding, exposing the group that most needs protecting from the virus by exposing them to the group that is apparently best able to resist it.

And then there is the problem of bored teenagers, congregating in shopping malls, or each other’s houses, again spreading the risk of disease in an unplanned, unplannable way.

For the British have not ruled out shutting the schools, or closing down the football grounds. They just say not yet.

On Friday evening, Professor Edwards and other speakers said more dramatic measures will be rolled out, possibly as early as the end of next week and certainly in the weeks ahead.

Media sites have also begun reporting that the UK government will start to ban large gatherings, including sports events, from next week.

Scotland has already announced a ban on outdoor gatherings of more than 500, and the Premier League has suspended its matches until April after a number of top players and some coaches tested positive.

Media reports suggest the public backlash is pushing the government to take these actions, and the opposition parties are starting to rise up, sensing a weakness in Boris Johnson’s position that they have not seen until now.

So timing may well be the essence of politics and disease management, as well as comedy.

We applaud all three when carried off with perfect timing: but get the timing wrong, and you can expect the boos, catcalls, heckles and worse … and right now, nobody is in the mood for laughter.