We publish this article by the British Marxists of Socialist Appeal, because we believe it’s a very important one, in order for someone to understand what is really going on in Britain. In this first part of the article you can find the significantly reasons that have led the British capitalism into a crisis. Britain’s industrial base declined, whilst there has been a great rise of the financial capital. Manufacturing shrank as the British ruling class sought making money for money. “The British economy has suffered a decline of more than 7% in GDP since 2008, which is worse than in the years of the Great Depression”, as it is mentioned on the document. Social inequalities have widened the gap between the rich and the poor. The British workers have become the victims of brutal exploitation. The majority of people living in London are forced to pay more than 60% of its income to rent a house. A plan to convert the British worker into “a Chinese one” is fully implemented. In this fight against the British working class, the mainstream union trades seem to be on the wrong side. Nevertheless the citizens of Britain are becoming radicalized.

Stathis Habibis

“The contradictions undermining British society will inevitably intensify. We do not intend to predict the exact tempo of this process, but it will be measurable in terms of years, or in terms of five years at the most, certainly not in decades. This general prospect requires us to ask above all the question: will a Communist Party be built in Britain in time with the strength and the links with the masses to be able to draw out at the right moment all the necessary practical conclusions from the sharpening crisis? It is in this question that Great Britain’s fate is today contained.”

– Trotsky, Where is Britain Going?

The crisis which began in 2008 represents a turning point. With the profound break in the situation, internationally and in Britain, the pace of events has greatly accelerated. A thorough grasp of perspectives is therefore essential for all comrades, without which, in the words of Trotsky, “we would be doomed to wander in the dark”. Of course, Marxist perspectives are not a blueprint, but an analysis of the underlying processes unfolding in society. They represent an important guide to action, and serve to orientate the tendency in the stormy period that opens up. They must be sharpened and reworked as events unfold. They should be read in conjunction with our documents on world perspectives, without which it is not possible to understand developments in Britain or elsewhere.

Marx explained that the key to the development of history and of society generally is the development of the productive forces: industry, technique and science. When a society is no longer able to develop the productive forces, it enters into crisis and opens up an epoch of social revolution. That is the current situation facing us on a world scale. It is a confirmation of historical materialism.

We have entered the most disturbed period in history. Crises – political, economic, social, diplomatic, moral, etc. – are endemic at all levels. This is a reflection of the exhaustion of the capitalist system, which can no longer develop the productive forces in any meaningful way. The capitalist system has reached its limits, as in the 1930s, when world growth was temporarily reinvigorated only following a catastrophic world war. Now as then, important sectors of the economy simply stagnate and decay. Even the bourgeois economists describe it as “zombie capitalism”, half alive and half dead, kept alive by historically low interest rates. The route of escape used by capitalism in the 1930s is closed because a new world war (which would presumably be nuclear) is inconceivable. In 2008, the implosion of the world economy was averted by an enormous programme of Keynesian spending (led by China), but today growth in the Chinese economy is slowing and the level of global debt is astronomical. The system has entered a protracted period of terminal decline, which has far reaching consequences.

As Trotsky explained in The Death Agony of Capitalism and the Tasks of the Fourth International, “The bourgeoisie itself sees no way out… Conjunctural crises under the conditions of the social crises of the whole capitalist system inflict ever heavier deprivations and suffering upon the masses. Growing unemployment, in its turn, deepens the financial crisis of the state and undermines the unstable monetary systems.” This describes accurately the main features of the capitalist system at the present time.

“The objective prerequisites for proletarian revolution have not only ‘ripened’,” explained Trotsky, “they have begun to get somewhat rotten.” It is the subjective factor that is lagging behind.

There is no real recovery anywhere, over seven years since the slump. Where there has been growth, it has been anaemic and fragile. The system has simply staggered from one crisis to another. The world economy is mired in “secular stagnation”, as the bourgeois economists like to call it. The epoch of reforms has ended. The epoch of counter-reforms and savage austerity has begun. No country is immune from this process. It determines the fate of all governments that operate on a capitalist basis, openly bourgeois or reformist.

In the coming year or so, capitalism is likely to experience a new world slump that could lead to a new world Depression as in the 1930s. This will exacerbate everything, plunging countries into deeper crisis and provoking revolutionary upheavals everywhere. Over the next decade, with the deepening crisis of capitalism, there will be a whole series of decisive showdowns, including in Britain. This is the very nature of the epoch.

If we are going to fully appreciate the epoch that lies before us, we should arm ourselves by reading Trotsky’s Where is Britain Going? and his extensive writings on Britain in the 1930s, which are very relevant today and remain a treasure-trove for Marxists. They are vital weapons in the preparation of the cadres.

THE DECLINE OF BRITAIN

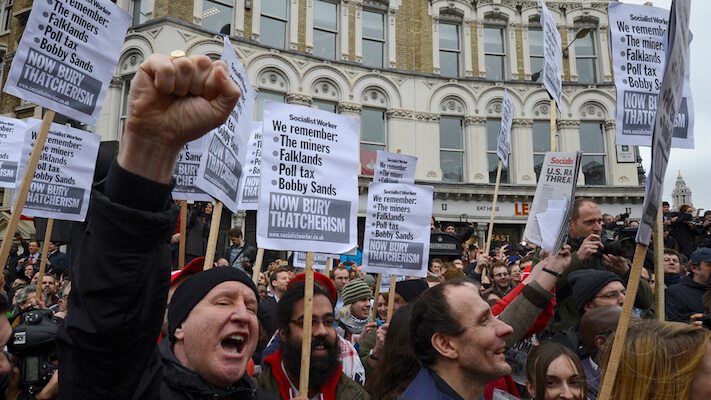

On top of the worsening crisis of world capitalism, which has become a permanent crisis, is the special crisis of British capitalism. This special crisis reflects the complete bankruptcy of the British ruling class in failing to invest and develop industry, preferring instead to engage in speculation and other such ventures. They were seeking to make money from money, without the trouble of producing things, as Marx had explained long ago. The British bourgeoisie have presided over an ignominious decline in British capitalism, again reflected in a steep decline in its industrial base. For decades, this process of decline has gone on, but it greatly intensified under Thatcher. As a result, the former workshop of the world has become a second-rate power, a shadow of its former self.

Hand in hand with the decline in industry went the rise of finance capital. As manufacturing shrank, the service sector swelled to colossal proportions. Banking and insurance became increasingly powerful, especially following the deregulation of the finance sector in 1986. Financial and banking regulations were put on the bonfire. The financial services went from strength to strength, until it became the dominant force behind British capitalism as well as its Achilles’ heel.

The British economy has taken on the characteristics very much of a rentier economy, as the French had been for most of the 19th century and early 20th century, but such a system was imposed not upon a peasantry, as in France, but on a strong industrial working class. The crisis of British capitalism meant that one industry after another went to the wall. This deindustrialisation would have serious consequences for British workers in terms of employment and living standards.

In 1979, manufacturing industry accounted for almost 30% of national income and employed nearly 7 million workers. Today, it has been reduced to 10% of national income and employs around 2.5 million workers. Over the last 30 years, it has shrunk by two-thirds in size, the greatest deindustrialisation of any major capitalist power. The brunt of this decline has occurred in Scotland, Wales and the north of England, where much of this manufacturing took place, creating a stark divide between northern and southern England. At the same time services, banking and finance have mushroomed. Since the 2008 slump, the service sector has grown by 11%, but manufacturing has declined by 6,5%. Today, financial services account for 15% of GDP, which has doubled in the last 15 years. The City of London has been transformed to a world casino in finance and insurance, a magnet for “hot money”, international money laundering and speculation.

British banks have grown to become the biggest in the world. Their loans and investments are equal to more than 5 times Britain’s annual GDP. Proportionally, British banks are 6 times bigger than US banks. London is the centre now of world finance and world usury. 41% of all financial transactions are carried out through London. It has 70% share of trade in global bonds and 47% share in trade in derivatives. This amounts to a daily turnover of $1.4tn.

London too has become the home of the super-rich, buying up property and forcing up house prices. It has become a billionaires’ playground. They build luxury swimming pools in the basements and dig down to construct several floors below street level. Many of these properties are simply held as unoccupied investments for bourgeois landlords, compounding an already-drastic housing crisis. At present, there are an estimated 218,000 empty properties in Britain, nearly all of them privately-owned. They stand as testament to the irrationality of a system that builds for no purpose other than profit. This, along with galling developments such as ‘poor doors’ in London tower blocks have provoked widespread outrage from large sections of the masses, providing us with fertile ground for propaganda and agitation.

Rather than stability, such a financial and banking edifice dominating the economy has dynamite built into its foundations, creating shocks and profound instability. British banks are dependent not on British customers, but on raising their money from the international bond market and foreign banks. Financial wizardry has mushroomed internationally, feeding on historically low interest rates. In 2008, derivatives, namely fictitious capital, had grown to $500 trillion, 10 times the size of the world economy. Crisis prone financial markets, in the form of unregulated shadow banking, will spill over into Britain, creating financial havoc. Such crises will strike London hard, given its global position. With global financial power comes global financial crisis.

This has been one of the reasons why British capitalism was the hardest hit of the G7 powers in the last world slump. The British economy has suffered a decline of more than 7% in GDP since 2008, which is worse than in the years of the Great Depression. In the autumn of 2008, British banks were facing total collapse, threatening to drag the whole economy down with them, only to be bailed out by the New Labour government using taxpayers’ money.

Financial services are parasitic by their nature. They do not produce surplus value, but simply siphon sit from the productive economy. An economy based simply on services is dependent on others and is extremely vulnerable as a result.

The strategists of capital had given up on the idea that Britain could compete industrially. They were incapable of restoring the power of British industry on the world stage. With the defeats inflicted on the working class in the 1980s, the ruling class turned decisively towards developing the service sector and financial services. Today’s talk by Osborne, the Tory chancellor, of the “march of the makers” is so much hot air at a time when the steel industry is on the point of collapse. The parlous position of the steel industry, the bedrock of any industrial economy, is a real reflection of the state of British capitalism. In fact, the whole of the manufacturing sector is smaller than it was before the 2008 slump by about 7%. Construction also continues to contract. The result of this demise for the working class has been the creation of a low wage, low skill economy, based upon sweated labour, and largely reliant upon services for employment.

As a consequence of this drastic shift, the current account deficit has reached £100bn a year, considered crisis levels in normal times. This deficit is the difference between all of Britain’s income and all she spends in terms of international trade. The British government has only managed to disguise this deficit by the flow of international finance into Britain, regarded as a safe haven for financial speculation. As long as these flows can be maintained, they serve to paper over the gaping cracks that exist.

British manufacturing, although reduced in size, is not “leaner and fitter” as the Tories claim. Its competitiveness lags far behind that of its international competitors. Labour productivity in the US was 31% higher than in the UK in 2013, measured in output per hour worked. In Germany it was 28% higher, in France it was 27% higher and even in Italy it was 9% higher. This is due to much lower investment or lower capital stock per worker in Britain, as well as lower skills levels, and lower expenditure on research and development. In 2010 for instance, total R&D expenditure grew (in real terms) in Germany (3.7%), Japan (1.4%), Italy (1.3%) and France (1.2%), but in the United Kingdom it declined by around 3%.

The consequence of this decline of British capitalism has meant a serious decline in the position of British workers, who have become the subject of brutal exploitation, both in the private and public sector. British workers work longer hours than their counter parts in any of the EU-15 countries, have the worst employment protection, get the lowest number of holidays, and get the lowest benefits for the first year of unemployment. Workers in Britain are regarded as the most “flexible” labour force in Europe, a fact trumpeted by the employers. There are more agency workers in Britain than the rest of the EU combined, reflecting the savage attacks on the British working class.

British capitalists are relying increasingly on cheap labour, which is not able to effectively compete with advanced technology and productive industry, like the German economy. This is where the short-sightedness of the British ruling class has brought us. They abandoned their past role of developing the productive economy and have become get-rich-quick merchants. The sucking in of international finance into the City of London has served to push up the value of the pound, thereby pushing up export prices and undermining dearer British exports. This means the British economy is being built on a financial faultline and is vulnerable to all kinds of shocks. The next world slump will shatter this feeble foundation and plunge the working class into a further nightmare.

ASSAULT ON THE WORKING CLASS

The working class has been under the hammer for more than 30 years, following the defeats of the 1980s and more recently. However, this brutal assault has intensified since the slump of 2008. Working life has become harder, more difficult and stressful. The regime in the workplaces has become increasingly repressive, as the squeeze on the working class intensifies. The capitalists have used their whip hand to tear up terms and conditions across the board. There is growing resentment in the workplaces, but there are also growing fears of what the future holds. Insecurity has rocketed as workers are threatened with redundancies and job cuts. Work in Britain has become increasingly casualised. Before the war, dock workers were lined up every morning while the gaffer chose those who could work that day. Now people on zero-hour contracts simply receive text messages to tell them when they can work. Many workers, especially the youth, are reliant on several jobs to make ends meet. Minimum wages have become the maximum in most work places.

“The 40-hour week is long gone,” says Karyn Twaronite at Ernst & Young. The number of people working more than 48 hours per week had risen by 15% since 2010 to nearly 3.5 million. In London, some 100,000 are said to be on zero-hour contracts, and three-quarters of a million nationally, soaring by a fifth in the last year.

This relentless attack has resulted in a two-tier workforce, where there is a margin of security amongst older established workers, but for the young workers there is nothing but insecurity, not knowing from one day to the next how much they will get.

“Jobs for life” are a thing of the past. Stable work has been replaced with short-term contracts and self-employment, with all the insecurity that goes with it. Since 2008, only 1 in 40 jobs created were full-time jobs, a startling figure. This means no sick pay, no holiday pay, no maternity pay, nothing. The Tories say this shows an increase in “entrepreneurship”, but in fact it shows how desperate things have become.

“The poorest fifth of British households are among the most economically deprived in Western Europe and suffer levels of poverty on a par with those in the former eastern bloc, according to researchers”, states the Financial Times.

“The High Pay Centre, an independent UK think-tank, has published analysis of OECD data showing “life is much worse here than it is for the poorest fifth in virtually every other north-west European country…

“According to Eurostat, the EU’s statistical agency, gross domestic product per person is lower in west Wales than in Poland. Similarly, GDP per head in Tees Valley and Durham is lower than in the Czech Republic.” (17/6/14)

For many, the slog of work has become an enduring nightmare. In the public sector, workers have been on the defensive for years. In the private sector, 14.4 million people work for SMEs (workplaces of less than 250 employees) which are predominately non-unionised and where bosses rule dictatorially with little regard to legal workers rights. The vast majority of such workers have no union and no immediate prospect of joining a union. The extent to which these workers have been hit in terms of pay, stress, instability, bullying, harassment and unsafe conditions is very high. This is also the case for other non-unionised workers, agency workers and those on casual contracts. Even the public sector, which has much stronger unions and where workers are generally in better off positions, has been on the defensive for years. There has never been so much resentment in work. Pent-up anger, frustration and bitterness are at record levels. Such is the fear that millions of workers go to work when they are sick and unfit for work. Stress has resulted in a 40% rise in mental health problems in the past 12 months. This is a brutal time and workers are drawing their own conclusions from this state of affairs.

“If only I could get a steady job that paid decent wages”, has become a dream for many. “If only I could get a decent place to live on reasonable rent”, is an ambition that now seems impossible.

The housing crisis has reached levels not seen since the 1930s. In London, a majority of people pay over 60% of their income on rent. Obtaining a secure council tenancy has become nearly impossible. Millions are on the waiting list, whilst no new homes are built. Skyrocketing house prices, a symptom of the decay of British industry, mean that access to home ownership is now the preserve of the wealthy and their children. As such, millions of young people are forced to live longer with their parents, or to rent overcrowded and poor quality homes in the private sector. Many, especially the youth, look to the future with dread.

This overall pressure is not simply bearing down on manual workers, but is widespread amongst the so-called white collar professions. The recent example of the strike ballots of 40,000 junior doctors, who voted by 98% to go on strike, on a 75% turnout, the first time in over 40 years, is a clear symptom of the growing ferment.

The deeper you go down into the working class the more explosive is the mood. This is especially the case amongst the most oppressed layers, which no longer see any prospects of change in front of them. Already this generation has a lower standard of living than their parents and the situation is quickly deteriorating.

As a consequence, Britain has never been so polarised. A massive gulf exists been the super-rich and the mass of society, which is struggling to make ends meet. The super-rich are bringing in foreign workers as domestics. According to Kevin Hyland, the new anti-slavery commissioner, about 17,000 domestic servants are being brought into the country each year, and some are suffering a “shockingly terrible” existence. According to Human Rights Watch, some employers called them abusive names such as “animal” or “dog”, or threatened to harm them. They work from 7am until 10pm or midnight and generally live in box cupboards and annexes.

The employers are continuing to turn the screw. As the Tory minister Hunt explained, the British workers now need to work as hard as their Chinese counterparts. This is simply a race to the bottom, which is preparing an almighty explosion. There are limits to everything and in Britain they are being reached.

TRADE UNIONS

This mood of discontent is however being held back by the trade union leaders, who are terrified of unleashing a real struggle or making any real effort to recruit and organise the mass of non-unionised workers. They have become increasingly divorced from the real mood in society and are acting as a massive brake at the present time. Rather than organise a fight-back, they sow despondency.

Under pressure they organised the mass demonstration against the government in 2011 of up to a million workers, followed by the big strike over the threat to pensions in November of that year. This showed the potential for a struggle. But since then they have called sporadic protests, without any real intent, but in order to blow off steam. The public sector pay freeze was imposed without serious opposition, despite enormous potential. When UNITE was faced with a serious challenge in the Grangemouth petro-chemical plant and refinery, they capitulated. They threw away a golden opportunity to launch a struggle against the employers’ offensive. Of course, weakness invites aggression. In a vindictive fashion, the government started to get rid of the Check Off system, beginning with the civil service. The union leaders were divided over the issue, which only served to isolate the PCS union that faced the brunt of the attack. Now the government feels confident enough to extend their attacks.

However, the threat of industrial action by junior doctors, who have become radicalised in the face of government attacks forced the government to backtrack temporarily. Rather than turning public opinion against the junior doctors, opinion has rallied behind them. The possibility of picket lines outside hospitals, after their retreat on tax credits, has forced the Tories onto the back foot. A determined stand could force the government into a wholesale retreat. As with tax credits, they can make tactical retreats, but will step up their attacks in other areas.

This dispute of junior doctors is very symptomatic. This layer has not seen industrial action since 1972. They are a young, fresh workforce who, under attack, were quick to respond. The fact that we have a former comrade in the leadership has played an important role in the dispute, which again underlines the importance of the subjective factor. The action or threat of action is a sign of things to come as the scale of the cuts become evident.

The seething anger that exists will eventually find its expression in the trade unions, as more workers turn to them in defence of their terms and conditions. This can bring about a renewal in the unions with a new more radical leadership emerging at a local and national level. Explosions are inevitable in the next period as the employers tighten the screws. Local authority workers can be a flashpoint given the severity of the cuts. So could the growing layers of extremely casualised workers, often not organised by the trade unions. These workers do not see the unions as a credible force because the trade union leadership has taken no interest in organising them, or cannot even conceive of defending workers who do not have rights enshrined in bourgeois law. To a large extent the trade union leadership have succeeded since the crisis in dampening interest in the trade unions as a point of reference for discontent. However, a movement of such casualised layers would not be fighting to defend their terms and conditions, but to improve them. Given the atomised conditions of casualised work, any offensive movement would very soon have to acquire a political character against casualised labour in general. This too could give an impulse to the radicalisation of the traditional trade union movement. While a layer of older workers attempt to keep their heads down, looking towards retirement, there is no such escape for the majority of workers. In the coming period, the severity of the cuts will provoke a massive reaction. There can be a social explosion if they push things too far. The trade union leaders will be forced to put themselves at the head of a movement in order to keep it under control. However, they are sitting on a live tiger that is becoming increasingly restless. If they do not express this mood, they will be replaced by those who will.

The Tory government is trying to prepare for this eventuality by rushing onto the statute books new anti-trade union legislation. The new barriers imposed on the right to strike, by increasing the legal threshold in strike ballots, will not stop what is coming. Such laws will be brushed aside when the workers move. Already amongst the junior doctors, the steelworkers, tube workers and others, the turnouts and votes for action have been extremely high, far in excess of the government thresholds. Rather than hold things back, they can radicalise the situation even further as resentment reaches boiling point.

We are told that the fall in living standards, the worst for more than 100 years, has now ended. According to the government, living standards are going up with the fall in prices. This is government propaganda and a complete sham for the vast majority of workers, who are faced with increased rents, council tax and transport costs. Many workers and their families are shelling out up to half their income on rent. In the south east of England, up to 13% of income goes on transport costs. This situation affects the youth especially hard. Research has shown that one in five Britons fall below the poverty line once housing costs are taken into account. In London, it is one in four.

There has been no let-up in the squeeze, with one million people reliant on food banks. Up to a third of food bank users had their benefit payments sanctioned (reduced or stopped), pushing families into crisis and debt.

In this explosive situation, the industrial front can be radically transformed. Any revival in the economy, however brief, can also give an impetus to the industrial struggle, as workers fight to recover lost ground. Whatever happens, the working class will go through a profound political radicalisation in the face of increasing attacks from employers and government.

To be continued…