by Jean P. Joubert

Can it be that there are eloquent silences in Trotsky’s writings? The question may seem ridiculous, for, in truth, it seems difficult to trace any secrecy in them. From this point of view, the “closed” section of the Harvard archives has revealed secrets; it has disclosed lies, the reason for which can easily be understood. It leads to dossiers which had been regarded as closed being re‑opened. But it has not revealed a different personage. The fact remains, none the less, that there is in Trotsky’s work a fundamental, voluntary self‑censorship. To his last breath, Trotsky remained a Soviet patriot. He never permitted himself to reveal the state secrets of the Soviet Union, about its intelligence services, its diplomacy or its armed forces, secrets which he possessed thanks to his former important responsibilities (1).

What does this censorship imply? We know the brilliant writings, in which he analysed, with a lucidity un‑paralleled at the time, the reality of the Nazi threat. We know his implacable criticism of the policy of the German Communist Party. The writings from 1930 to 1933 are on a par with the proclamations which he wrote during the Russian Revolution and the Civil War. In them Trotsky did not limit himself to analysis, but fought inch by inch, right up to the last, to try to change the policy which, he was convinced, would lead to the triumph of barbarism and to war. It was Stalin who dictated this policy. Trotsky knew this, and said so. But was Stalin “mistaken”? Was his policy the result of “mistakes”? Trotsky wrote often to this effect. But what were the roots of these mistakes. Were there not “reasons” in Stalin’s policy, and, in particular, considerations of foreign policy? Trotsky has little to say on this point, and this may seem curious.

The German‑Policy of the K P D: Leftism and Nationalism

The campaign connected with the Referendum of August 9, 1931 in Prussia is without doubt the most spectacular aspect of communist policy in the years of Hitler’s rise. The Referendum was held on the initiative of the Stahlhelm, an official offshoot of the Reichswehr, in order to force the dissolution of the Prussian Landtag and the dismissal of the Social‑Democratic administration. It found the Communist Party fighting against Social‑Democracy, by the side of the Nazis and the Stahlhelm.

This policy was not entirely new in 1931. Since 1928 the Communist International had been engaged in a policy of which it is hard to say whether it was “ultra‑left” or “ultra‑right” (2). The situation was characterised as “revolutionary”, and Social-Democracy was re‑christened as “social‑fascist” and presented as the main enemy. This ferocious attack on Social‑Democracy was complemented by the development of highly nationalist themes. In 1929 the K.P.D. was involved in a vigorous campaign against the Young Plan. On October 16, 1929, the Central Committee published an important declaration that the question of reparations could be settled only by “the violent, Bolshevik annulment of all the robbers’ treaties”. The Ten‑Point declaration of the Political Bureau on June 4, 1930, followed by the “Programmatic Declaration for the National and Social Liberation of the German People” on August 24, 1930, with the elections in view, took up themes and slogans of the nationalist extreme right, to such a point that Volkischer Beobachter wrote that the German Communist Party, with its policy of “liberation”, “had stolen the Nazi programme”.

While the Nazi extreme right was flooding the vocabulary of politics with innumerable variations on the word “Volk,”, the Communist Party adopted the slogan of “People’s Revolution”, which the Central Committee officially recognised in January 1931 as a strategic slogan. It abandoned all reference to class, emphasised the “realism” of its position towards war and made much of the military qualities of the proletariat and the necessity to create a Red Army (3).

The “Scheringer line” was a practical application of this orientation (4). Lieutenant Scheringer believed in the national revolution. In his search for a Fuhrer who would be able to take the leadership of a conspiracy, he had been in contact with the principal nationalist leaders, in order to find out whether they were prepared to to undertake to overthrow the government, in opposition to the dictated peace of Versailles and the policy of “fulfillment”. Scheringer was arrested in March 1930 and sentenced in September to imprisonment in a fortress for a year and a half. While his trial was go on, the Communist Party leader, Heinz Neumann, had a secret meeting with Goebbels According to a rumour, Neumann appealed to Goebbels to change the orientation of the Nazi Party and to direct its violent attacks away from the Soviet Union in order to attack France. He is said to have declared that the Red Army was ready to play the role of an army of liberation in Germany, and to have insisted that the “fratricidal war” must cease.

Contacts with the Nazi chiefs went on in public at the beginning of January 1931 On January 6, Willy Muenzenberg received the S.A. leaders, Otto Strasser and Karl Otto Paetel (7) in the office of the Comintern journal, Rote Aufbau. Scheringer had had close contact in the Moabit prison in Berlin with Communist leaders who were also jailed there, and, in particular, with Hans Kurella, the chief editor of Imprekor, the journal of the Communist International. On March 18, 1931, the Communist deputy, Kippenberger, who was in charge of the military apparatus of the K.P.D., read to the Reichstag a declaration, in which Lieutenant Scheringer announced that he had joined the Communist Party “as a soldier in the front of the proletariat, ready to defend itself” (Wehrhaft). Scheringer referred to his struggle for the national and social liberation of the German people, accused the National Socialist Party of having betrayed socialism, and declared that liberation could be achieved only through an alliance with the Soviet Union and the destruction of the capitalist regime in Germany by revolutionary war to defend the proletarian fatherland against the imperialist states and the forces of intervention: “We are par excellence the party of war. We shall make war in a truly revolutionary way”. (8) This declaration obviously was drafted by Kippenberger’s staff. Scheringer also mentioned that the Communist fraction in the Reichstag had declared, in the debate on the military bidget, that the Communists were in favour of “improved defences” (Wehrhaftmachtung), “of all the German working people”, for “a German army ready to fight and to struggle”.

In July 1931 Scheringer’s name was immortalised in a journal, Aufbruch, “the journal for struggle on the lines of Lieutenant Scheringer”. Aufbruch brought together leading Communists such as Kippenberger, old Nazi leaders and ex‑officers including Count Stenbock-Fermor, who had taken part in the Free Corps in the Baltic countries and had earlier boasted of having shared in anti‑Bolshevik atrocities. One of the first articles in Aufbruch signed by Heinrich Kurella (Scheringer’s former companion in captivity) was entitled “Communism and Nation”. The Aufbruch circles organised conferences on such subjects as “The Reichswehr and the Red Army”.

Trotsky against National‑Communism

On August 25, 1931, Trotsky, then in exile on Prinkipo, wrote an article significantly entitled “Against National Communism: The Lessons of the ‘Red’ Referendum”. Oddly enough, this article was translated into French under the title “Against National‑Socialism” (9), an un‑acceptable translation, because Trotsky was arguing not against National Socialism but against the Communists’ policy of concessions to the Nazis. The quotation marks around “Red” are very important. Trotsky aimed at denouncing the decision of the K.P.D. to vote with the Nazis and the Stahlhelm, by baptising as “Red” the referendum which the Nazis called “Brown”, as if changing its colour changed the content of the vote. When Trotsky used the title, “Against National Communism”, he was, to all appearances, going back consciously to the polemic of Radek, Lenin and Thalheimer ten years earlier against the “National Bolshevism” of the Hamburg group led by Laufenberg and Wolfheim (10).

According to Trotsky, it was fear of Nazism, since Nazism had become a mass movement, which led the K.P.D. to make “a new turn away from and to the right of the Third Period”, with its policy of liberation. The K.P.D. rejected what Trotsky regarded as the only effective form of defence, the formation of the united front of the working class, which meant abandoning the theory of “social‑fascism” and “the search for agreements with diverse Social‑Democratic organisations and fractions”. By doing so, the leadership of the K.P.D. was involving itself in “the most fallacious”, “most dangerous” policy, consisting of “passively adapting itself to the enemy and flying his colours” and straining to out‑do him in patriotic shouting. Trotsky regarded these, not as methods and principles of class politics, but as “forms of petty bourgeois competition”.

Of course, Trotsky says, every revolution is “popular” and “national” in the sense that it draws around the working class all the living forces of the nation. But this “sociological description” cannot take the place of the slogan of action. As a slogan, it is empty boasting, it is charlatanism, it is market competition with the fascists, paid for at the cost of injecting confusion into the minds of workers. The slogan of “People’s Revolution” in effect wipes away the ideological frontiers between Marxism and Fascism. It reconciles part of the workers and the petty bourgeoisie to the ideology of fascism, because it permits them to believe that they do not have to make a choice, being concerned both here and there with “People’s revolution”.

The crime of the Stalinist bureaucracy, writes Trotsky, is that, with Scheringer’s help, it solidarises itself with the nationalist elements, it identifies their voice with that of the party, it refuses to denounce their nationalist and militarist tendencies, it converts the profoundly bourgeois, reactionary, utopian, chauvinist pamphlet by Scheringer, into a new gospel for the revolutionary proletariat. It is a fact, he concludes, that the former worker, Thaelmann, does his utmost to avoid being inferior to Count Stenbock-Fermor (11.).

Trotsky did not deny the existence of a national question in Germany. But he did deny that a policy could be based upon it. He had written, on September 26, 1930, that the declaration of the Central Committee boiled down in the end to saying that, if the German proletariat took power, it would tear up the Versailles Treaty. He asked ironically: would the abrogation of the Versailles Treaty be the highest achievement of the proletarian revolution? (12) Less than a year later he again concluded his analysis of the article by Thaelmann which introduced the turn towards the “Red” Referendum:

“At the most important place in his conclusion Thaelmann puts the idea that Germany is a ball in the hands of the Entente. It is in consequence a matter of national liberation.”

In Trotsky’s opinion the national question is a question “of secondary importance”. The policy of the Communist Party cannot be determined by the fact that Germany is a ball in the hands of the Entente, but by the “interests of the divided German proletariat”, which had become “a ball in the hands of the German bourgeoisie”, because it was divided.

There could be no question of replacing the class‑struggle with national unity, on the pretext of the national question. On the contrary, the policy of Communists should be in these circumstances to return to the formulation of Liebknecht, “the most dangerous enemy is in our own country”. In any case, he added, the national question could not be solved by the “negative” slogan of abrogating the Treaty of Versailles, which was also the slogan of the Nazis. It called for a positive response in an international setting and could not in any case take the form of war against the West:

“The revolution is not for us a subordinate means for war against the West, but, on the contrary, a means for avoiding wars, in order to end them once and for all… The ‘national liberation’ of Germany lies, to our mind, not in a war with the West, but in a proletarian revolution, embracing Central as well as Western Europe, and uniting it with Eastern Europe in the form of a Soviet United States” (13).

Trotsky then mentioned the role of Stalin. “Stalin is silent”, he wrote, “but this whole policy is inspired by the master of the Kremlin”:

“Stalin worked through his agents in the German Central Committee and himself retired ambiguously to the rear.”(13)

However, with great prudence, Trotsky did not go into Stalin’s motives. However, he did hint at them. On September 30, 1930, he wrote that it was indispensable to purge the K.P.D. of the poison of national socialism, “the essential element of which is the theory of socialism in a single country”. He returned to the same idea on August 25, 1931, when he wrote that it was the “genuinely Russian” theory of socialism in one country” which inevitably fostered the development of “social‑patriotic” tendencies in the other sections of the Communist International (14)

The Third Moscow Trial and Russian Foreign Policy

Stalin was the first to lift a corner of the curtain. The Third Moscow Trial unfolded in 1938, and in the course of it, what was alleged to be the treachery of Marshall Tukhachevsky and of “the bloc of the Rightists and Trotskyists” for the benefit of Germany, was denounced. According to the indictment, the investigation and the admissions of the defendants revealed that there had been collaboration in the past between Trotsky and the Reichswehr. Contact was alleged to have been established in June 1920 between Trotsky and General von Seeckt, through the agency of Kopp. During the winter of 1921‑22 discussions were said to have taken place in Berlin, which resulted in a formal agreement between Krestinsky and Generals von Seeckt and Haase. Krestinsky was said to have undertaken, on the orders of Trotsky and with the help of Rosengolts, to arrange for espionage on the territory of the Soviet Union, to get visas for spies and to provide secret information about the air forces of the Soviet Union. Seeckt was said to have undertaken in return to provide Krestinsky with 250,000 gold marks annually, to finance Trotskyist counter‑revolutionary work. This was said to have actually been paid, sometimes in Moscow and at other times in Berlin. In 1926 the Reichswehr was said to have talked of breaking this off, but Trotsky’s promise to grant concessions, especially in mining if the Trotskyists got power in the U.S.S.R., enabled the collaboration to go on. The agreement was said to have become active in 1923 and to have been respected right up to autumn 1930, when Krestinsky left Berlin. In September 1933, when Krestinsky was passing through Berlin, he was supposed to have been contacted by Alfred Rosenberg, who wanted to conclude a secret deal with the Trotskyists to provide for the cession of the Ukraine to Germany. Trotsky was supposed then to have declared for collaboration with the German government and no longer only with the Reichswehr, and to have worked for a German attack on the U.S.S.R.in the hope of provoking the collapse of the Soviet government. Krestinsky was said to have met Trotsky secretly in September 1933 at Merano, in Italy, when the group of activists whose task it was to penetrate the Red Army, such as Tukhachevsky, Kork, Yuborevich and Putna, to have agreed with the idea of opening the front if the Germans attacked.

Trotsky could not remain silent in the face of this accusation. In self‑defence, he was obliged to break his self‑imposed silence about the military policy of the U.S.S.R. He could denounce several specific points in the indictment as gross falsifications (15), but he confirmed in general outline that there had been real collaboration with the Reichswehr, for which, as People’s Commissar for War, he had been responsible. He only made clear that this collaboration was not collaboration between Trotskyists and the Reichswehr in order to overthrow the Soviet Government, but collaboration between the Soviet Politburo and the Reichswehr, and that Stalin could try to make him responsible for it in 1938 because it had been secret and ultra‑secret.

Trotsky in fact made clear that very few people on the Soviet side knew what was going on. He said even that many of the Politburo of 1933 would know nothing about it:

“In the secret archives of the military commissariat and the G.P.U. there should undoubtedly be documents in which the collaboration with the Reichswehr is mentioned, in the most guarded and conspiratorial terms. Except to people like Stalin, Molotov, Bukharin, Rykov, Rakovsky, Rosengolts, Yagoda and another dozen or so of individuals, the contents of these documents may well seem ‘enigmatic’, not merely to prosecutor Vishinsky, who at that time was in the camp of the Whites, but likewise to several members of the present Politburo.”(16)

Trotsky explains that the collaboration began effectively when he was Commissar for War. Stalin knew about it because he was a member of the Politburo, and the policy went ahead under Stalin’s direction, because he was one of its most devoted supporters, even after Hitler had come to power.

Trotsky explains that when this policy, which was kept secret on both sides because it was carried out in violation of the Versailles Treaty, was introduced under his leadership, the Soviet Government was seeking a “defensive alliance” with Germany against the Entente and the Versailles Treaty. Social‑Democracy was playing an essential role in Germany at that time. It feared Moscow and placed all its hopes on London and Washington. The Reichswehr caste, on the other hand, despite its hostility to Communism, regarded as necessary a military and diplomatic collaboration with the Soviet Republic. Trotsky did not think that he had to describe the form of the collaboration in detail. None the less, he made clear that Germany could develop the forbidden armaments and training in this way in Russia, while Russia enjoyed the benefit of the development of German military technique. The collaboration included heavy artillery, aviation and chemical warfare. Russian war industry was “open to German experience”; “concessions” were awarded on Russian territory, especially to the aeronautical firm Junkers. They involved the entry into the U.S.S.R. of numbers of German officers, while officers of the Red Army visited Germany. Trotsky adds that, under his direction, this collaboration did not “yield many results”, essentially because both the Germans and the Russians were short of capital and also because they mistrusted each other. However, Trotsky did not say a word about the existence of common strategic aims.

German ‑ Soviet Collaboration

Subsequent research essentially confirms Trotsky’s 1938 version (17). None the less, it is clear that, when he placed his main emphasis only on the material aspects of this collaboration between the Reichswehr and the new‑born Soviet state, he played down considerably what it implied in strategic and political terms, following the first World War and the Versailles Treaty, with the intersection of the interests of the German army and the Soviet state.

We are concerned here with collaboration between the German army and the Soviet government. We are not dealing with any collaboration between the German army and the Red army, as Western commentators too often write, curiously accepting the Stalinist allegation in the Moscow Trials of military collaboration committing the two armies. This distinction is important. Of course, we are essentially dealing with military collaboration affecting both armies. Development of weapons and of German training camps in the U.S.S.R., training technical personnel and exchanging officers at the highest level, imply common strategic objectives. But on the German side, the Reichswehr was operating in secrecy, not merely in relation to the victor powers of Versailles but to its own government. Some German politicians were well informed, and concealed the complicated financial operations necessary to finance the purchases of the Reichswehr. But the policy of the General Staff of the German army was an independent one. On the Russian side, on the contrary, the operations were carried out on the initiative of the Politburo of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. To this day, nothing has come to light, to our knowledge, to give the slightest support to the central thesis of the Moscow Trial about the Russian army acting independently, or, a fortiori, about independent activity conducted in connection with Trotsky.

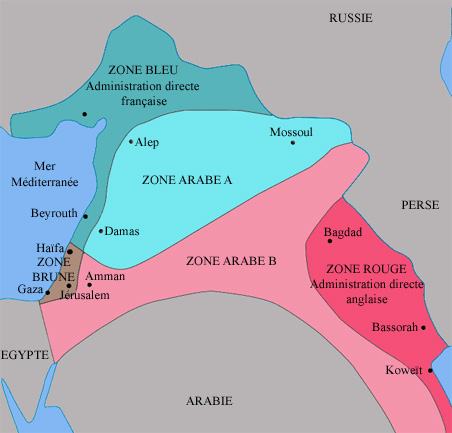

It was General Seeckt who, after the first world war, involved the Reichswehr in a policy very different from that of his predecessors, Ludendorff, von der Golz and Hoffmann. He gave up the white counter‑revolution against Bolshevism, accepted the Weimar Republic, refused to march in support of the Kapp putsch, and resolutely advocated a military alliance with the U.S.S.R., which he did not consider to be in contradiction with the struggle against Communism in Germany. The first documents to establish Seeckt’s new orientation with certainty date from February 1920. His thesis could not be more clearly formulated. Germany must win back her position as a world power. She could not do so without first having recovered the military apparatus of which the victors deprived her. She had to achieve this in a European context characterised by the domination of France. In the eyes of von Seeckt, the policy to be followed was dictated by geography, maps and the relation of forces. Germany could win back the position of a great power only by an alliance with the U.S.S.R. This alone could be a counterweight to French and British interests. Germany needed a strong Russia, whatever her political regime might be. German policy would be the same towards Russia whether she were ruled by the Tsar, by Kolchak or by Denikin. The sole strategic aim was to recover a common frontier with Russia, and to wipe out the “succession” states constructed by the victors at Versailles to erect a wall between Germany and Russia, Poland, Lithuania, Latvia. The destruction of Poland, the pillar of the French continental system, was a vital question for Germany, whose aim must be to recover the 1914 frontiers. Von Seeckt repeated this in 1922, at the moment when he refused (though only for short-term reasons) to consider common action with Russia. The existence of Poland was intolerable and incompatible with the survival of Germany. Poland must disappear as the result of its own internal weaknesses, thanks to Russia and with the help of Germany. Again in 1933 Seeckt summed up his conclusions, in a pamphlet: he showed that for centuries the policy of France had consisted of advancing into the East and, by the interposition of Poland, of compelling Germany always to fight on two fronts: he advised those responsible for German policy to take care in all circumstances to secure that freedom of their rear which only solid friendship with Russia could ensure.

It can, therefore, be said that from 1920 to 1933 and even beyond it was the common denomination of Poland, much more than the need of Germany to re‑arm with Russian help, which was the primary motive of the Reichswehr chiefs. The weakness of Russian industry and the difficulty of finding capital would in fact make technical collaboration difficult, and would mean that numerous projects would only be partially completed.

The foreign policy of the German government fluctuated, oscillating between the policy of Rapallo and that of rapprochement with the victors, marked by entering the League of Nations, by the Locarno Treaty and by the pro‑Western policy of Stresemann. Meanwhile, the policy of the Reichswehr did not waver an inch. It is true that von Seeckt had to give up his positions in 1926, and that his departure was the occasion for a formal attack on the Reichswehrpolitik by the Social‑Democrats. However, the later statements by General von Hammerstein, who had been involved from the beginning with Generals von Blomberg and von Schleicher in the secret collaboration and were responsible for continuing it from 1933 to 1934, is quite definite. Von Seeckt’s Russian policy was continued unchanged after his departure. The Reichswehr succeeded even in following this policy after Hitler came to power. For several months, in fact, Hitler continued to place confidence in the military, and we have to wait until the middle of the year 1933 for Hitler to take the initiative which put an end to the Reichswehrpolitik (18).

The Reichswehrpolitik intersected with the policy of the Soviet Union. The new, post-1919 Poland was a greater threat to Russia than to Germany. In Spring 1920 Pilsudski launched his attack in the direction of Kiev, while France occupied Frankfurt. On August 16, 1920 the counter‑offensive of the Red Army was checked in front of Warsaw. Despite the contacts which had already been made (19), the military weakness of the Red Army and the non‑existence of the Reichswehr prevented the two forces from joining up, and demonstrated that the two armies had to be reconstructed before there could be any strategic alliance. If Germany and Russia were to ally their forces, then they could try to break open the grip of the Entente and to crush the arrogance of Poland. Once again, in 1923, it seems probable that only the threat of German intervention paralysed Poland, and prevented her from taking advantage of the French occupation of the Ruhr to lay hands on Upper Silesia.

The Russians carefully guarded the secret of the collaboration, but Lenin made no mystery of the motives which inspired it. At the Eighth Congress of the Soviets in December 1920, he explained that the German bourgeoisie was obliged, particularly by the Versailles Treaty, to seek an alliance with Russia. Lenin’s foreign policy was essentially a defensive one. He attached little importance to territorial gains, but showed himself to be above all concerned to make the economic connections necessary to the development of Russian industry, and, on the level of strategy, to disrupt the front of the capitalist powers and to gain time, while awaiting the European revolution and its vanguard, the German revolution. On this level there was complete agreement between Lenin and Trotsky.

It was, no doubt, not always easy to reconcile help to the revolutionary struggle with agreements between states. In 1923, therefore, the trade in arms with the Reichswehr continued while the German army was employed in repressing the workers’ insurrection.

The Russians were realists: it was clearly understood that revolution is not exported on the points of bayonets . The searing experience with Poland was rich in lessons on this point.’ In 1923 Trotsky had to mention this rule again, and to repeat that it was out of the question for the Soviet Union to come out militarily to the aid of the German revolution.(20) In an advanced country, he explained, the revolution can conquer only if it can find sufficient forces on the national soil. For all that, taking account of the interests of the Soviet state did not yet imply subordinating the revolutionary struggle to the diplomatic and military interests of the Soviet Union. This is precisely what changed in the years 1924 ‑ 25.

The K. p.D. and Soviet Foreign Policy

Nothing but the opening of the Soviet archives will enable this still‑forbidden zone of historiography to be illuminated. However, we must note that there are some disturbing coincidences. Considerations of Soviet foreign policy seem to have greater and greater weight: the coincidence between the tactic of the K.P.D. and the Soviet diplomatic game cannot be ignored as the K.P.D. became more and more closely subordinated to Stalin (21).

It is clear that neither the Russian nor the German Communists had any reason to love Social‑Democracy. The revolution had drawn a line of blood between them and the socialists. In Russia, Social‑Democracy had opposed Soviet power arms in hand. In Germany Social‑Democracy was deeply involved in the assassination of Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg, and civil war had divided Socialists from Communists.

More precise considerations came to supplement these historical and sentimental points. In Germany Social‑Democracy was more hostile to collaboration with Russia than any other party. Several times Socialist deputies had used the Reichstag as a platform to denounce the military collaboration of the Reichswehr with the Red Army, for example, Hermann Muller in 1922 and Schiedmann in 1926. They obliged the Soviets to hide their collaboration still more deeply (22).

The S.P.D. was the only German party to have a policy frankly oriented towards the West, where the member‑parties of the Second International were dominant. It favored a German policy of abandoning resistance, of seeking compromise with the victors of Versailles; this took form in the policy of Stresemann, the Locarno Treaty and the Dawes and Young Plans.

Gustav Hilger, who held a strategic position in the German embassy in Moscow for twenty years, has recorded how much more intense was the hatred of the Russians for Social-Democracy than their hostility to bourgeois or feudal reaction. He has shown that the Kremlin worked hard to prevent the establishment of a Socialist government in Germany. Chicherin and Litvinov even discussed openly with the German diplomats the need to keep the S.P.D. out of public affairs (23).

It is possible that already in 1925 the intervention of Stalin was decisive in the policy which enabled Hindenburg to be elected President of the Republic. In any case, his election pleased Stalin. He regarded it as a sign that Germany was resisting the Versailles powers (24). We must say that at this time the German Socialists, who were formally in opposition, but who ruled in Prussia, supported the idea of a security pact, which was finally signed at Locarno in October 1925, in concert with the “Left Bloc” in France and with the Labour Party in Britain.

Moscow mobilised all its resources against the Western orientation of Germany which the Social‑Democrats advocated. The efforts of Soviet diplomats had little effect, and it seems likely that the K.P.D. was mobilised to serve this purpose. The 1928 Congress of the Communist International was followed by an important intervention from Moscow, which imposed on the K.P.D. an intransigeant struggle against Social‑Democracy and a violent, nationalist campaign against any rapprochement with the Western powers and against the Young Plan, against which agitation developed in autumn 1929 and during the winter (25). In 1931 it was Moscow that reached the deliberate decision to co‑operate with the Nazis and with the Reichswehr‑controlled Stahlhelm in order to drive the Social‑Democratic government out of office in Prussia (26). At the same moment, on June 24, 1931, an agreement was signed in Moscow prolonging the German‑Russian Treaty of 1926 and the convention of 1929.

As a whole, the re‑doubled violence of the K.P.D. towards Social‑Democracy and use of nationalistic themes seem to be quite consistent with Stalin’s “.purely Russian strategy”, organised in Germany round the Reichswehr and certain sectors of heavy industry. Stalin was attached to this alliance because it dealt essentially with a military agreement aimed against the very real threat from Poland. The fact remains that, in this strategy, the reality of the Nazi danger was for Stalin a factor of the second or third order. He was convinced, in fact, that the leaders of the “pro‑Russian party”, Generals Blomberg, von Hammerstein and von Scleicher, would be able to keep the Nazis in check. He was to retain this illusion, it seems, for several months after Hitler took power.

Trotsky: An Alternative Foreign Policy?

‘We can easily understand why Trotsky said nothing about the secret collaboration with the Reichswehr. In full agreement with Lenin, he had been chiefly responsible for this policy, which was put into effect by his direct collaborators, Kopp, Rosengolts and Rakovsky.

But the Nazi menace profoundly modified the disposition of forces. At the end of 1931, it was necessary to “sound the alarm” in the face of the probable consequences of a Nazi victory. Trotsky explained that this would mean the extermination of the elite of the German proletariat, the destruction of the Communist International in a repetition of August 4, 1914, and war against the U.S.S.R. In the face of such danger military and diplomatic deals were of no avail. Nothing but general mobilisation could save the situation. Once again, here was the former chief of the Red Army speaking. He addressed the militants of the German Communist Party, the Social‑Democratic workers and the non-party workers, not merely because what was at stake went far beyond Germany alone. He wrote that Germany was not only Germnny, but the heart of Europe: Hitler was not only Hitler, but a “super‑Wrangel”, who could come to power only at the end of a pitiless civil war: the Red Army was not only the Red Army, but “the instrument of the world proletarian revolution”.

His proposals were clear: the attempt of the fascists to take power must result in the mobilisation of the Red Army. He returned to this question in Spring 1932, in an interview aimed at the American public but also at the opponents of Stalin, who were organising. He stressed that the German attack on the Soviet Union if the Nazis won in Germany would be merciless, nor did he hesitate to say “what he would do”, if he were in the place of the Soviet government. As soon as Hitler came to power, convinced that he faced a situation which could be resolved only by war, he would sign the order for general mobilisation, with the purpose of not giving Hitler time to establish and to strengthen himself, to make alliances, to get the support he needed and to draw up a plan of military aggression, “not merely in the East but in the West”. He added that it was of no importance to know who would formally take the initiative in armed combat, because a war between the Hitlerite state and the Soviet state would be inevitable and would break out quickly.

But he went no further. He did not say a word about the Reichswehrpolitik, though it is clear that he believed that this policy was no longer relevant, and that the preparation of the U.S.S.R. for war involved a search for other military alliances. The coming to power of Hitler can only have strengthened him in his convictions. None the less, in Spring 1933, he was in fact isolated in a completely un‑real picture. In Berlin, the Reichswehrpolitik did not yet seem to be called into question. In May 1933 Hitler repeated to his ambassador, von Dirksen, his desire to pursue good relations with Russia, on condition that the latter did not interfere in the internal affairs of Germany. In Berlin von Dirksen saw many people, Hindenburg, Goring, Goebbels and Frick. When he returned to Moscow, he told his collaborators that the Nazi government wanted to stabilise its relations with Russia. Meanwhile Hitler was playing a pacifist comedy on the other front, to catch the ear of Britain and to isolate France. Again Trotsky warned the Soviet leaders, but also those of the `Western democracies. They would be mistaken if they were reassured by Hitler’s moderation. While it was true that he wanted above all to march against the Soviet Union, the fact still remained that “the weapons which could be used against the East could just as well be used against the West”.

A Return to the U.S.S.R.?

The evidence which continues to be absent from the history books will indeed one day have to receive notice. Trotsky was alone in his time in seeing correctly what the Soviet and Western leaders could not see. The policy which he advocated in 1931 was to be that which Stalin was obliged to operate amid catastrophe and at the cost of millions of lives, when the German divisions spread out over the plains of the Ukraine, only a few months after the Reichswehrpolitik was realised and Poland disappeared from the map. The map had also to be cleared of the Western democracies and there had to be years of the brown plague for the strategic alliance contained in Trotsky’s 1‑31 analysis to be realised in the entry of U.S.A. into the war.

Was Trotsky a “Prophet Dis‑Armed”? To be sure, the formula is seductive, but it has the weakness of those who conceive history in terms of accomplished facts. In reality, it is likely that several questions have to be re‑examined, beginning with this one: Does the return of Trotsky to the U.S.S.R. have to be regarded as science‑fiction? The documents in the file that we have to go on are not yet very numerous, but they occupy a certain space.

We have Trotsky’s secret letter to the Politburo of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, dated March 13, 1933, in which he expresses his sincere intention of co‑operating with every tendency in the face of such a great danger. Would he have written this letter if he had not had several good reasons to expect that it would receive an echo in the Soviet leadership? Can it possibly be reduced to the level of a mere propaganda exercise? (27) We also have the various rumours that were floating about Europe, that, for example, in the German liberal journal, Vossische Zeitung, which had passed into Nazi control. This suggested that Trotsky might return to the U.S.S.R. Anyway, the rumour acquired enough substance for the important Paris daily, Paris‑Soir, to send the journalist, Georges Simenon, to Prinkipo, to put the question to Trotsky (28): “Some newspapers have claimed that you have recently received emissaries from Moscow with instructions to demand that you return to Russia.” Simenon pressed the point: “Would you resume active service?” He wrote: “He replied ‘yes’ with a movement of the head”. At the end of June 1933 the Soviet press agency TASS denied the rumours: its declaration was, no doubt, a reply to German questions as to the possibility of a turn in Soviet foreign policy.

These rumours show that the question of Trotsky’s return to the U.S.S.R. was raised not only by him but also by Berlin and Moscow. Was the same question likewise posed in Paris? The file about the visa which the Daladier accorded to Trotsky is far from being closed. What is established is that Trotsky himself did not believe that the French government could possibly take this course. He wrote to his translator, Parijanin, “I can hardly imagine that the French government will give me a visa, especially at this moment, when it is seeking unity with Stalin.”(29) The French government could hardly have been unaware of the rumours which found their way even into the big newspapers about the isolation of Stalin and the impact of Trotsky’s articles on leading circles in Russia. What were the political considerations, if there were any, which impelled the government of the Radical, Daladier, the man of confidence of the French General Staff, to grant this visa?

Finally, there are two elements essential for the file which are due to the discoveries of Pierre Broué about the Bloc of the Oppositions and about what we know of the assassination of Kirov in December 1934. Pierre Broué has demonstrated that there was a regroupment of the oppositions against Stalin operating in the U.S.S.R. in 1932, and that this regroupment was in secret communication with Trotsky (30).

We also have strong grounds for believing that in December 1934 Kirov was assassinated by Stalin, after he had made contact with Trotsky in order to consider in what conditions Trotsky might return to the U.S.S.R.(31). None of these documents, to be sure, is conclusive, but none the less there emerges from them a hypothesis, that the Soviet leadership was much less homogeneous than the picture which many Kremlinologues present, and that the temptation to recall the former head of the Red Army and to realise national unity against the danger of Nazism was strong. These leaders did more than think about this solution: they began to take action, and paid with their lives. In any case, there can be no doubt that the coming years will make new contributions, probably from Moscow itself, to this file.

FOOTNOTES

(1) We are not dealing here with Russian patriotism, but with patriotism towards a state which Trotsky believed, despite its profound degeneration, to be a “workers’ state” and a form, though doubtless the worst possible, of the dictatorship of the proletariat.

(2) Neumann entered the Politburo of the K.P.D. in 1928. He was the incarnation of the new ultra‑left, nationalist orientation. Perhaps thanks to his perfect knowledge of the Russian language he found himself accepted by Stalin as an intimate. He played an essential part in elimination, on Stalin’s behalf, the team of Maslov and Ruth Fischer, which was linked to Zinoviev. He can also be regarded as the “eminence gris” of the new leadership of the K.P.D. under Ernst Thalmann.

(3) See Dupeux G., “National‑Socialisme, strategie communiste et dynamique conservatrice”, Paris 1919.

(4) Scheringer was charged with making propaganda for national‑socialism in the army and having supported an activity consisting of high treason aimed at changing the Constitution of the Reich. General Groener, the Reichswehr Minister and a personal friend of von Schleicher went on record in support of punishment. The Scheringer trial took place through September 1930 in Leipsig. Hitler was called as a witness and played the comedy of legality. The President of the tribunal took note that the witness Hitler, since 1923 has never acted but in a legal way, and that he did not tolerate subversion in the Reichswehr. During the trial the militant national‑socialist crowd shouted, “Long Live the National‑Socialist Reichswehr”. In Scheringer’s eyes, Hitler had betrayed the cause of the national revolution when he took the oath of legality. See J. p.Faye, Langages Totalitaires, Paris 1972.

(5) He also met General Reinhard, one of the strong men of the two marches on Berlin, the Noske march and the Kapp Putsch, then the heads of the Stahlhelm and then those of the S.A.

(6) According to J. p.Faye, Langages Totalitaires, p.544, Goebbels was ‘known to favour a German‑Russian alliance. On October 1, 1925 appeared the first issue of “N.S. Letters” (NS.Briefe) (“National‑Socialist Letters”). The second issue carried Goebbels’ “Letter to my friend of the left”, under the headline, “National‑Socialism or Bolshevism”, in which he wrote that “you and I are fighting without really being enemies”. No. 4 of this journal published a third article by Goebbels, on the “Russian question”; it suggested that it was in the alliance with a “genuinely national and socialist” Russia that we recognise “the beginning of our own national and socialist self‑affirmation”.

(7) J. p.Faye, op. cit., p.420.

(8) Dupeux, op. cit., p.567.

(9) The Struggle against Fascism in Germany, Pathfinder, New York, 1971, p.93, under the title “Against National Communism (Lessons of the ‘Red Referendum)”.

(10) In 1919 Laufenberg, an old socialist influenced by Lassalle, an anti‑militarist who had been close to Liebknecht during the war, who had come over to Communism and was chairman of the Hamburg Workers’ council during the 1918 revolution and was the devoted supporter of the councils, which he counter‑posed to the party, began to develop an ultra‑nationalist line; this was labelled “National‑Bolshevik” and stood for transforming the revolution into a “revolutionary war”. He supported the idea of renewing the war in the West against the Versailles Treaty, by beginning with an offensive on the East in order to effect union with the Red

Army. At the same time he ceased entirely to talk about “class” and placed the word “People” in the centre of his vocabulary, explaining that it was necessary to unite the whole people for the war. In the end he effected contact with the nationalist circles.

Thalheimer and Radek undertook the polemic against the Hamburg group. In Radek’s open letter to the Heidelberg Congress of the K.P.D. (October 1919) which excluded Laufenberg, written from prison, he declared that, in certain conditions, it was conceivable that the Communist Party could have contacts with “loyally nationalist” officers, but that, on the contrary, there could be no place in its ranks for a tendency which, under the mask of radical Communism, “transformed foreign policy into a national policy and placed the interests of the Nation above that of the classes. This would be a new version of the “sacred union”, out of which could come nothing but “a petty bourgeois rationalist party”.

In May 1920, Lenin attacked the “ridiculous absurdities” of the “National‑Bolshevism” of Laufenberg and others” who wanted to propose a bloc with the German bourgeoisie in order to re‑commence the war against the Entente within the framework of the international proletarian revolution. (“Left‑Wing Communism”, in Lenin, Collected Works, Vol. 31, p.75). Lenin argued that the national problem could not be erected to the position of an absolute rule. To fix liberation from the Versailles Treaty as the first task was “petty‑bourgeois nationalism”. The aim was to overthrow the bourgeoisie in “every great European country”, an overthrow which would be such an advantage to the international revolution that “we could and, if necessary,should agree to prolong the existence of the Versailles peace”. (Ibid., p.76‑7)

In Lenin’s opinion, as in that of Radek, it was not a question of involving oneself in military adventures against the Treaty of Versailles and still less that of abandoning the class struggle in order to do so. There can be no doubt that Trotsky shared this appreciation at the time. This critique of “National-Bolshevism” formed an integral part of the heritage of the K.P.D., which was formed precisely in a split from the “Lefts” of the K.A.P.D., of which Laufenberg became one of the leaders. Ten years later, this was the critique to which Trotsky returned in opposition to the leadership of the K.P.D., which had adopted a policy closely resembling that which Laufenberg had advocated in 1919.

(11) Following this document, Count Stenbock‑Fermor wrote a letter to Trotsky, which shows that the latter had an obviously incorrect appreciation of Count Stenbock-Fermor. The text of this letter is reproduced, in French, in Cahiers Leon Trotsky, No. 36, p.51ff.

(12) The Struggle against Fascism, p.71, entitled, “The Turn in the Communist International”.

(13) Ibid., p.106, entitled, “Against National‑Communism”.

(14) Ibid., p.106.

(15) He proved that he had not had the material possibility of meeting Krestinsky in 1933 and declared that there had been no meeting between Sedov and Rosengolts at Karlsbad in 1933, and that he himself had not seen Marshall Tukhachevsky since 1925. See Leon Trotsky Writings (1937 ‑ 38), p.236ff, under the title, “Moscow’s Diplomatic Plans and the Trials”. The preparation of the trial had coincided with a period in which Moscow’s hopes in the Popular Front were vanishing and in a block of the democratic powers likewise. (Dated March 8, 1938)

(16) Ibid., p.210ff, under the title “The Secret Alliance with Germany” and dated March 3, 1938 .

(17) These researches are based essentially on the papers of General von Seeckt, who headed the Reichswehr from March 1920 to October 1926. He was the inspiration of the pro‑Soviet policy of the German army, a policy which was continued without significant change after General von Seeckt was removed. The French and Polish secret service materials which Castellan has analysed provide useful contributions. The balance‑sheet of the investigation is drawn by F. L. Carsten, in Survey, October 1962, Vol. 19, “The Reichswehr and the Red Army”.

See also E. H. Carr, “Socialism in One Country”, Vol. 3, p.1,010ff.

(18) At the end of the month of April 1933, the Soviet ambassador Khinchuk was received by Goring, and then by Hitler, who assured him that nothing had changed in the relations between the two countries. See, in particular, Jacques Grunewald, “L’evolution des relations germano‑sovietiques de 1933 a 1936”, in Les Relations Germano‑Sovietiques de 1933 a 1939, Paris 1954, pp.7‑42.

(19) According to E. H. Carr, The Bolshevik Revolution, p.324, an unpublished text by Reibnitz, written towards 1940, communicated to Carr by Gustav Hilger, reports that Reibnitz had negotiated with Radek and Kopp for the German free corps to advance through East Prussia up to the old German frontier when the Red Army entered Warsaw. According to the confessions of Krestinsky at the Third Moscow Trial von Seeckt was in contact with Kopp at that time in July 1920.

See also the letter to von Seeckt of Enver Pasha of August 26, 1920: “I have spoken to the really important personage, Trotsky. We have here a party which possesses real strength, and Trotsky, who is a member of it, wants an agreement with Germany. The party would be prepared to recognise the old 1914 frontier of Germany. In order to help the Russians, see could raise an army of volunteers or provoke an insurrection, perhaps in the Corridor or in an appropriate place.”

(20) Leon Trotsky, September 30, 1923, “Conversation with the American Senator King”, Izvestia, 30 September, 1923:

“We do not intervene in foreign civil wars, that is perfectly clear. We could only intervene by declaring war on Poland. But we do not want war. We do not hide our sympathy for the German working class in its heroic struggle for its liberation. To be more precise and frank, I would say: if we could give victory to the German revolution without risking entering a war, we would do our utmost. But we do not want war. War would damage the German revolution. Only the revolution which succeeds thanks to its own strength can survive, especially when a great country is concerned'”.

(21) It is difficult to accept on this point the explanation which Fernando Claudin gives in La Crise du Mouvement Communiste, Paris, 1972, p.189. He correctly mentions that the blindness of the Communist International to the rise of Hitler cannot be explained solely as the result of an accumulation of mistakes, as Dimitrov claimed at the 7th Congress, but Claudin draws the conclusion that we are dealing here with a profound sickness: “Atrophy of theoretical faculties, bureaucratisation of organisational faculties, sterilising monolithism, unconditional subordination to the manoeuvres of the Stalinist camarilla.”

These factors are far from being negligible, but we have to recognise that the “manoeuvres of the Stalinist camarilla” possess a logic which was not governed merely by the atrophy of their faculties, real though that was. Thomas Weingartner, Stalin and der Aufsteig Hitlers, Berlin 1970, thinks that considerations of foreign policy have an essential weight in this analysis.

(22) E. H. Carr, The Bolshevik Revolution, p.435.

(23) Walter Laquer, Russia and Germania, London, 1965, pp. 135 ‑ 6. We should add that it was at the Fifth Congress of the Communist International that the distinction which had been drawn at the Fourth Congress between fascism and bourgeois democracy became blurred. The theses of the Fifth Congress stated that “the more bourgeois society decomposes, above all the bourgeois parties and the Social Democracy especially, take on a more or less fascist character.” It was shortly after the Fifth Congress (June ‑ July, 1924 that Stalin deepened still further the formulae of Zinoviev about social‑democracy and fascism: “Objectively Social‑Democracy constitutes the moderate wing of fascism” (Stalin: Oeuvres, Vol. 6, pp.296‑299.We should note that Trotsky dates the theory of social‑fascism from 1928, while the first elements of it incontestably were earlier.

(24) Stalin, Oeuvres, Vol. 7, p.100.

(25) Beloff, The Foreign Policy of Soviet Russia: 1929 ‑ 1941, p.62.

(26) It was no doubt to cover this policy that Pravda published on July 2, 1931, a forgery intended to “prove” that Trotsky was an ally of Pilsudski and a defender of the Versailles Treaty against the U.S.S.R. and Germany. See Trotsky, Writings: 1937 ‑ 38, p.281ff, under the title “Moscow’s Diplomatic Plans and the Trials”.

(27) Ibid.

(28) Trotsky, interview with Georges Simenon, in Francis Lacassin and Gilbert Sigaux. Simenon, Paris, 1973, pp.309‑320.

(29) In Spring 1933, faced with the danger from Hitler, the French Government pressed on with the efforts which it had begun in 1932, in view of the reality that Germany was re‑arming, with the aim of an agreement with the U.S.S.R. The first object of this was to break the links which had united Germany and the Soviet Union since Rapallo. The longer‑term problem was to revive the old system of French defence, based on the Franco‑Russian alliance, in view of the fragility of Poland and the Little Entente. The U.S.S.R. was under threat in the Far East, and accepted a Franco‑Soviet Non‑Aggression Pact proposed by Herriot in 1932. The Russian concern was above all to cover the Western frontier so as not to be threatened with a war on two fronts.

(30) Pierre Broué, “Trotsky and the Bloc of the Oppositions”, Cahiers Leon Trotsky, No. 5, 1980, pp.5-38, and Pierre Broué, “Re‑Groupment Against Stalin in the U.S.S.R.”, in Trotsky, Paris, 1988, pp.700‑712.

(31) J. J. Joubert, “The Kirov Affair began in 1934”, in Cahiers Leon Trotsky, No. 20, December 1984, pp.79‑93.