A new study says we’ve vastly underestimated the amount of heat trapped by Earth’s oceans due to global warming.

by Sarah Emerson

Nov 1 2018

On November 14, 2018 this paper’s authors announced key errors to the two week-old study that made claims about the amount of heat that Earth’s oceans have absorbed.

The errors stem from “incorrectly treating systematic errors in the O2 measurements and the use of a constant land O2:C exchange ratio of 1.1,” co-author Ralph Keeling said in an update from Scripps Institution of Oceanography, which is affiliated with the study. More simply, the team’s findings are too uncertain to conclusively support their statement that Earth’s oceans have absorbed 60 percent more heat than previously thought. Keeling claims the errors “do not invalidate the study’s methodology or the new insights into ocean biogeochemistry on which it is based.”

The journal Nature told the Washington Post on Tuesday that it is currently investigating the errors, and has not yet issued an update.

British scientist Nicholas Lewis was one of the first to dispute the findings, and wrote in a November 6 blog post that “a quick review of the first page of the paper was sufficient to raise doubts as to the accuracy of its results.”

Several climate scientists told the Washington Post they were glad the errors were caught early on, and that analysis of ocean warming is a tricky subject.

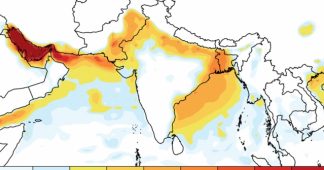

The world’s oceans have absorbed far more heat than we realized, shortening our timeline to stop the causes of global warming, and foreboding some of the worst case scenarios put forth by climate experts, according to new findings.

A novel study by researchers from Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California San Diego and Princeton University, published on Wednesday in Nature, implies that officials have underestimated the amount of heat retained by Earth’s oceans.

Between 1991 and 2016, oceans warmed an average 60 percent more than estimates by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) originally calculated, the study claims. That amount equalled 13 zettajoules, or eight times the world’s annual energy consumption.

The authors compared their results to the IPCC’s major 2014 report on climate change, which found that oceans consume more than 90 percent of excess heat accumulated by greenhouse gases.

“We thought that we got away with not a lot of warming in both the ocean and the atmosphere for the amount of carbon dioxide that we emitted,” the study’s lead author Laure Resplandy, a biogeochemical oceanographer at Princeton University, told the Washington Post on Wednesday.

“But we were wrong,” Resplandy said. “The planet warmed more than we thought. It was hidden from us just because we didn’t sample it right. But it was there. It was in the ocean already.”

A separate IPCC report published in October warned of catastrophic consequences—food shortages, worsening poverty, and the destruction of island nations by rising seas—as soon as 2040 if greenhouse gas emissions persist at their current rate, representing an atmospheric warming threshold of 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels.

The IPCC estimates that emissions must drop 20 percent by 2030, and hit net zero by 2075, to prevent warming from exceeding 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels. (The Paris Agreement aims to limit warming to the 1.5 degrees Celsius benchmark, and well below 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels, as the difference between the two could be disastrous for some regions.)

But the Nature report claims that emissions must be reduced 25 percent beneath the IPCC’s estimates to avoid the 2 degrees Celsius benchmark. Basically, global warming has begun to outpace the (comparatively) less extreme predictions for Earth’s future.

“If you look at [the IPCC’s 1.5 degrees Celsius estimate], there are big challenges ahead to keep those targets, and our study suggests it’s even harder because we close the window for those lower pathways,” Resplandy told BBC on Thursday.

The study is the first to have used a novel technique to measure the ocean’s heat content.

As the ocean warms, it releases oxygen and carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. The researchers relied on data from the Scripps Institution of Oceanography: measurements of oxygen and carbon dioxide in the air, collected from stations around the world since 1991.

With that information, “we can calculate how much warming we need to explain that change in gases,” Resplandy told BBC.

Scientists have historically measured the ocean’s temperature with thermometers. In 2007, the Argo program, an international collaboration meant to standardize ocean observation, was established, comprised of nearly 3,800 submersible robots called “Argo floats” that bob up and down, transmitting climate data via satellite.

Before 2007, “less than 1 percent of the ocean below the upper few hundred meters was being monitored routinely,” according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. And while the Argo program isn’t perfect, prone to gaps in coverage, it’s errors are averaged out, experts told the Los Angeles Times on Wednesday.

Some scientists not involved with the study are skeptical of its implications.

“Their estimates overlap with previous estimates, but it’s aligned with some of the higher estimates,” David Nicholson, an associate scientist at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, told the New York Times on Wednesday. “It’s not like completely changing our understanding of what the ocean might be taking up—it’s a new type of measurement that’s weighing in toward the higher end of that.”

“It’s an intriguing new clue, but it’s certainly not the case that this study alone suggests that we have been systematically under-representing the oceanic warming,” Pelle Robbins, a research specialist at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, told the Los Angeles Times.

Still, these findings could be used to hone current estimates about ocean warming and climate change. And while the Nature study is unique, “Other groups are measuring changes in atmospheric [oxygen] and [carbon dioxide], which would put them in a position to weigh in,” the study’s co-author Ralph Keeling, a climate scientist at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, told Motherboard.

“But none started as early as the Scripps program,” Keeling added. “So these groups cannot address the trends over such a long time frame. Still, I would expect other groups will start casting their results in the same terms, which is an important test.”

Warming oceans account for a long list of climate change effects, such as coral bleaching, widespread species decline, extreme weather events, and glacier melt.

More than one year has passed since President Trump announced that he would withdraw the United States from the Paris Agreement.

This story has been updated to include a comment from Ralph Keeling, co-author of the new study and a climate scientist at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography.