Thomas Fazi

Feb 01, 2026

The UN is weaker and more delegitimised than ever, but it would be a mistake to blame the institution for the world’s problems: the UN simply mirrors our our fractured geopolitical reality

The United Nations is facing the deepest crisis in its eighty-year history. Its legitimacy has been eroding for years, attracting criticism from across the political spectrum. Critics of US and Western foreign policy denounce the organisation as powerless in the face of mass slaughter in Gaza and repeated unilateral US military actions carried out without Security Council authorisation. Liberal Atlanticists fault it for its inability to halt Russia’s invasion of Ukraine or bring the war to an end. Meanwhile, the MAGA movement portrays the UN as an instrument of a “globalist elite” bent on eroding national sovereignty.

Today, however, the organisation confronts a more direct challenge: an open assault from the country that has long been its principal architect, sponsor and largest financial contributor — the United States. Donald Trump, a long-standing critic of the UN, has moved from rhetoric to action. Since returning to power, his administration has slashed voluntary contributions to UN agencies and withheld mandatory payments to both the regular and peacekeeping budgets. According to UN officials, the US currently owes billions of dollars in assessed contributions, prompting the Secretary-General to warn that the organisation faces the risk of “imminent financial collapse”.

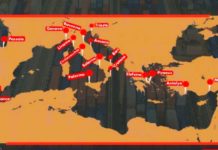

The pressure is set to intensify. Trump’s proposed 2026 budget would drastically reduce or eliminate funding for several UN bodies, including the regular budget and peacekeeping operations. At the same time, he has launched a parallel initiative — the so-called “Board of Peace” — explicitly framed as an alternative to the existing multilateral system and chaired by Trump himself. So far, only a limited number of countries, largely US-aligned governments in the Middle East, Central Asia and Latin America, have signalled participation. Notably, Western countries have declined or hesitated, while major powers such as China, Russia and India have refrained from formal commitment.

For these reasons, the initiative is unlikely to displace the UN in the near term, as it is rightly perceived as little more than a tool for projecting US power — and legitimising Trump’s cowboyish foreign policy. The UN system will thus probably endure, but in a weakened and increasingly contested form. This erosion of authority, however, cannot be attributed solely to institutional failure. The UN — like any international organisation — ultimately mirrors the global distribution of power.

This has always been the case. Despite the language of universal legality, international law has often been largely a myth, enforced selectively when it aligned with the interests of dominant powers and ignored when it did not. The 2003 US invasion of Iraq is a textbook example of this asymmetry. But it couldn’t otherwise: international law lacks an independent enforcement mechanism; there is no global police force capable of compelling compliance. Its force has therefore always been less coercive than normative — grounded more in legitimacy and shared expectations than anything else.

What distinguishes the current moment is not merely the persistence of power politics but the diminishing effort to cloak it in legal or moral justification. Previous US administrations at least sought the appearance of multilateral legitimacy; today, that veneer is gone. The UN has limited means to counter such unilateralism. Yet concluding that the organisation — or international law itself — is therefore obsolete would be a leap. Even without hard enforcement, international norms exert real influence. States, including powerful ones, remain dependent on alliances, trade and diplomatic recognition. Disregarding widely accepted norms carries reputational and political costs, as the global backlash against Israel and Trump illustrates.

A system in which states retain at least a normative incentive to respect shared rules is preferable to one governed openly by raw force. At the same time, it is unrealistic to expect the UN alone to resolve the world’s crises. The fate of conflicts in the Middle East, Ukraine or any other region is ultimately shaped by the broader balance of power rather than by resolutions passed in New York.

Meaningful change therefore depends less on institutional reform than on geopolitical accommodation among major powers. Should they succeed in forging a new equilibrium — a kind of updated global Westphalian understanding — the UN could regain relevance. If they fail, its capacity to prevent escalation will remain limited. In this sense, the organisation reflects the fractures and alignments of the international system itself.

But we should be clear about who the outlier is. On a wide range of issues, the global majority frequently votes with remarkable consensus, leaving the US and its closest Western allies isolated. Far from being detached from reality, the UN often mirrors it — a “world minus one”, as some have put it, or perhaps more precisely, a world minus the West.

What is clear is that a more balanced, cooperative and genuinely multipolar framework is urgently needed. The hope is that that this systemic reconfiguration can occur through negotiated accommodation rather than the mass conflict that catalysed the UN’s formation.

.

We remind our readers that publication of articles on our site does not mean that we agree with what is written. Our policy is to publish anything which we consider of interest, so as to assist our readers in forming their opinions. Sometimes we even publish articles with which we totally disagree, since we believe it is important for our readers to be informed on as wide a spectrum of views as possible.