By Radhika Desai

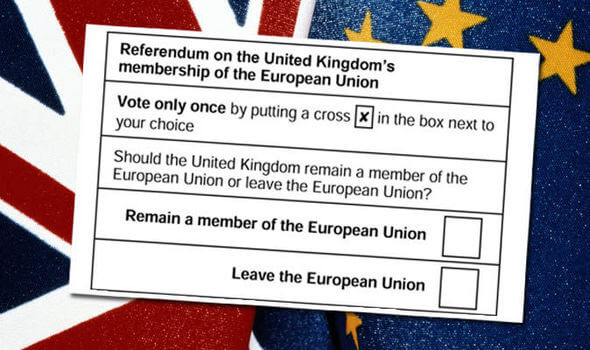

The Brexit vote was a momentous political earthquake and the seismic shifts that caused it have been long in the making. It has ruptured so many political structures — decades and even centuries old, national and international — so deeply it could be decades before its damage can be fully reckoned. The damage reveals the fragility of Britain’s, and the West’s, political and economic structures caused by three-and-a-half decades of neoliberalism and austerity.

The Bremainers’ entirely laudable cosmopolitanism and anti-racism were tragically mixed up with a blindness to how fast and how far formerly social-democratic Europe had become neoliberal. The Brexiteers staged the latest popular revolt against neoliberalism and austerity, as the Greeks and the inhabitants of Donbass did in 2014 and the supporters in the United States of Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders are doing today. Despite the entire political establishment and all its financial and media resources backing remain — with even Labour’s Euro-sceptic leader Jeremy Corbyn urging “remain and reform” — the English and Welsh electorates voted decisively for Brexit.

While Nigel Farage, the leader of the U.K. Independence Party and Tory Boris Johnson made racist appeals and there have been rising incidences of racist violence since the Brexit vote, most Brexiteers are not racist. They were rejecting the EU as the unelected enforcer of neoliberalism. The EU’s infamous democratic deficit is necessary to impose neoliberalism on social-democratically inclined populations. The largely right-wing leave campaign was aware of this, falsely claiming, for instance, that millions of pounds would be redirected from the EU into the National Health Service.

Brexit has revealed deep contradictions in both major parties. It was the decades-long fall in the Conservative party’s vote, most recently bleeding to the far-right UK Independence Party that led Prime Minister David Cameron to promise the ill-fated referendum so rashly, thinking nothing of dragging the entire country through a divisive and pointless referendum to solve an internal-party political problem. It has only become more acute: the Conservatives will now find it even more difficult to function as the party of property while retaining sufficient support to win elections.

Brexit has opened an equally fundamental divide in Labour. Socialist or social-democratic parties have typically been alliances between the manual working class and the professional and intellectual element, of what the Fabians, with quaint directness, called “brains and numbers.” Never easy — the social democrats split from Labour back in 1981 — this divide has been deepened by neoliberal inequality. The party’s “New Labour” professional elements dominate the parliamentary caucus while Jeremy Corbyn was elected leader with massive support from Labour’s union and working class base. This week, the parliamentary party attempted what former Scottish National Party leader, Alex Salmond, called a “disgusting coup” against Corbyn. If Corbyn wins the inevitably bitterly contested election, as he well might, Labour faces a deeper split.

Brexit has also disunited the Kingdom. Scots voted to remain. The SNP is promising another referendum on Scottish independence and leader Nicola Sturgeon was in Brussels to discuss Scotland’s continuing EU membership. Northern Ireland also voted to remain and Sinn Fein now wishes to open the question of Irish unification.

German Chancellor Angela Merkel and other EU leaders, aware of the dangerous example Brexit is setting, must now impose heavy penalties on Britain — though these will also hurt dominant EU interests — merely to prevent other countries from following suit. It remains to be seen whether they can impose these penalties and whether they will have the desired deterrent effect.

Internationally, Britain was the gateway into the EU for the U.S. and many other countries. Now, foreign companies that invest in Britain to access the EU markets will have to reconsider their strategies. The city of London, the financial sector that dominates the U.K.’s long deindustrializing economy, has suffered the greatest blow. It was led out of post-war doldrums by eurodollar business in the 1970s. Prime minister Margaret Thatcher’s first act in office was to lift capital controls and she followed it up with financial deregulation. Now London is Robin to New York’s Batman in the dollar-denominated international financial and monetary system, profiting from its vast asset inflations and torrential international capital flows that shored up demand for, and the value of, the U.S. dollar.

After they collapsed in 2008, however, international capital flows failed to recover and London became more reliant on Euro-denominated transactions. Its search for alternative business even led it to join China’s Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank over U.S. President Barack Obama’s loud and clear objections. Brexit not only threatens Euro-denominated business but also Chinese business: EU membership was part of the attractions of London for China.

Who knew when Cameron rashly promised to hold this referendum it would be a game-changer at so many political and geopolitical levels?

Radhika Desai is a political studies professor and the director of the Geopolitical Economy Research Group at the University of Manitoba.