By Mark Weisbrot

It is clear that the executive branch of the U.S. government favors the coup underway in Brazil, even though they have been careful to avoid any explicit endorsement of it. Exhibit A was the meeting between Tom Shannon, the 3rd ranking U.S. State Department official and the one who is almost certainly in charge of handling this situation, with Senator Aloysio Nunes, one of the leaders of the impeachment in the Brazilian Senate, on April 20. By holding this meeting just three days after the Brazilian lower house voted to impeach President Dilma Rousseff, Shannon was sending a signal to governments and diplomats throughout the region and the world that Washington is more than ok with the impeachment. Nunes returned the favor this week by leading an effort (he is chair of the Brazilian Senate Foreign Relations Committee) to suspend Venezuela from Mercosur, the South American trade bloc.

There is a lot at stake here for the major U.S. foreign policy institutions, which include the 17 intelligence agencies, State Department, Pentagon, White House National Security Council, and foreign policy committees of the Senate and House. An enormous geopolitical shift took place over the past 15 years, in which the Latin American left went from governing zero countries to a majority of the region. For various historical reasons, the left in Latin America tends to favor national independence and international solidarity, and is therefore less willing to go along with U.S. foreign policy. I remember the first time I saw Lula Da Silva. It was in Porto Alegre, Brazil, in 2002. He was speaking to a crowd at the World Social Forum, and standing under a huge banner that said “Say No to Imperialist War in Iraq.”

Lula is a good diplomat, and he maintained a good personal relationship with George W. Bush during their overlapping presidencies. But he changed the foreign policy of Brazil, and contributed to the regional development of an independent foreign policy. In 2005 at Mar del Plata, Argentina, the left governments buried the U.S.-sponsored “Free Trade Area of the Americas,” thus putting an end to the American dream of a hemispheric commercial agreement based on rules designed in Washington. Brazil under the Workers’ Party also strongly backed Venezuela against U.S. attempts to isolate, destabilize, and even topple its government. Lula’s first foreign trip after his re-election in 2006 was to Venezuela, where he supported President Hugo Chávez in his own re-election campaign. The Workers’ Party(PT) government also supported regional efforts to overturn the U.S.-backed military coup in Honduras, and successfully opposed the expansion of U.S. access to military bases in Colombia in 2009. And many in the U.S. foreign policy establishment (including then Secretary of State Hillary Clinton) did not appreciate the Brazilian government’s role in helping to arrange a nuclear fuel swap arrangement to settle the dispute with Iran in 2010, despite the fact that it was actually done at Washington’s suggestion.

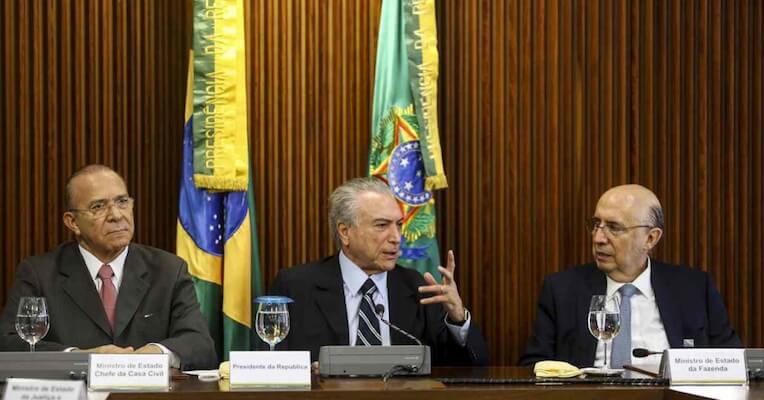

Washington’s Cold War never ended in Latin America, and now they see their opportunity for “rollback.” Brazil is a big prize, as is evidenced by the new foreign minister in the interim government. He is José Serra, who ran unsuccessfully for president against first Lula (2002) and Dilma (2010), and is expected to use his current position — if this government survives — as a springboard for a third shot at the presidency.

In his 2010 presidential campaign, Serra went to unusual lengths to demonstrate his loyalty to Washington. He accused the Bolivian government of Evo Morales of being an accomplice to drug traffickers and attacked Lula’s government for its attempts to resolve the nuclear standoff with Iran. He also criticized them for joining the rest of the region in refusing to recognize the post-coup Honduran government, and campaigned against Venezuela as well.

This is the kind of guy that Washington wants, very badly, in charge of Brazil’s foreign policy. Although corporations are obviously a big player in U.S. foreign policy, and they literally do much of the writing of commercial agreements like NAFTA and the TPP, the number one guiding principle in Washington’s foreign policy apparatus is not short-term profit but power. The biggest decision-makers, all the way up to the White House, care first and foremost about getting other countries to line up with U.S. foreign policy. They did not support the consolidation of the Honduran military coup because Honduran President Mel Zelaya raised the minimum wage, but because he headed a vulnerable left government that was part of the same broad alliance that included Brazil under the PT. These governments all supported each other, and they changed the norms of the region so that even non-left governments like Colombia under Juan Manuel Santos mostly went along with the others.

That is what Washington wants to change right now, and there is much excitement in This Town about the prospects for “a new regional order,” which is really the old regional order of the 20th century. It won’t succeed — even by their own measures of success — any more than George W. Bush succeeded in his vision of reshaping the Middle East by invading Iraq. But they could help facilitate a lot of damage trying.