Subject essay: Lewis Siegelbaum

The Bolshevik seizure of power in Petrograd in October 1917 was celebrated for over seventy years by the Soviet government as a sacred act that laid the foundation for a new political order which would transform “backward” Russia (and after 1923 the Soviet Union) into an advanced socialist society. Officially known as the October Revolution (or simply “October”), it was regarded by the Bolsheviks’ enemies — and continued to be interpreted by many western historians — as a conspiratorial coup that deprived Russia of the opportunity to establish a democratic polity.

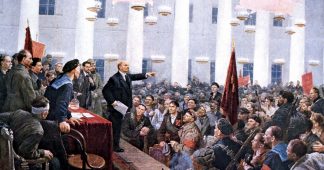

“The Bolsheviks, having obtained a majority in the Soviets of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies in both capitals, can and must take state power into their own hands … The majority of the people are on our side.” Thus did Lenin, still in Finland as a fugitive from arrest on charges leveled in the aftermath of the July Days, cajole his party’s Central Committee in September. Lenin’s assessment of the shifting balance of forces was acute. So was his sense of urgency. The leftward swing in popular sentiment after the Kornilov Affair was strengthening the Bolsheviks, but also the more radical elements of the SR and Menshevik parties committed to the establishment of an all-socialist coalition government. While most Bolsheviks also favored such an arrangement and looked forward to the Second All-Russia Congress of Soviets as the vehicle for delivering it, Lenin was adamant that only an insurrection could deal a decisive blow to the Provisional Government and the threat of counter-revolution. On October 10, having returned to Petrograd, he obtained, by a vote of 10-2, a resolution of the Central Committee in favor of making an armed uprising the order of the day.

It was a measure of the Provisional Government’s over-confidence and isolation that even after the two Bolshevik dissenters, Grigorii Zinoviev and Lev Kamenev, went public with their dissent, it did not take any decisive measures. In the meantime, the Bolsheviks managed to fashion the Military Revolutionary Committee (MRC) of the Petrograd Soviet into a command center for carrying out the insurrection. Kerenskii’s ill-conceived decision to shut down the Bolsheviks’ printing press, an action that evoked the specter of counter-revolution, turned out to be the impetus for the uprising. On October 24, Red Guards and soldiers under the MRC’s command, began to occupy key points in the city. By the following day, the assembled delegates to the soviet congress were informed that the Bolsheviks had taken power in the name of the soviets, and that they should proceed to form a Workers’ and Peasants’ Government. Within minutes, the battleship Aurora was bombarding (with blank shells) the Winter Palace, where most of the Provisional Government’s ministers waited in anxious expectation, and the Palace was stormed by Red Guards. As the Menshevik and SR delegates stormed out of the soviet congress in protest, Trotsky, the congress’ president, told them to join “the rubbish heap of history.”