By Ron Dudai

Aug 22, 2025

As Gazans document mass killing and starvation in real time, the response of much of Israeli society is: “It’s all fake — and they deserve it.”

A decade ago, in the final days of the weekly joint Palestinian–Jewish protests against Israel’s construction of the separation wall in the West Bank village of Al-Ma’asara, one of our pre-demonstration rituals was a speech by Mahmoud, a local community leader. Phone in hand, he would declare: “We will not have another Nakba, because now we have this. We have a smartphone. We have Facebook. They will try to drive us away again, but everyone will see it and stop it. In ’48 we had no smartphones, no Facebook. Now it will not happen.”

He repeated this mantra every Friday — to the activists beside him, to the soldiers facing us, and to himself. At the time, it felt reassuring. But he was wrong.

Israel’s ongoing genocidal campaign in Gaza may be the most thoroughly documented atrocity in recent history, measured both by the sheer volume of evidence and the speed of its circulation. Smartphones and social media — which were still a world away during the genocides in Bosnia and Rwanda — allow events to be captured instantly, from countless angles, and shared globally in real time, with traditional media still playing a not-insignificant supporting role.

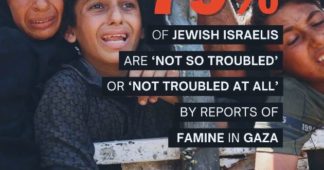

And yet, faced with an unending flood of photos and videos of dead civilians, starving children, and entire neighborhoods reduced to rubble, much of the Israeli public — and a significant portion of Israel’s supporters abroad — responds in one of two ways: either it is all fake, or else the Gazans deserved it. Often, paradoxically, it is both at once: “There are no dead children in Gaza, and it’s good that we killed them.”

A new era of denial

Atrocity denial is a global phenomenon, but Israeli society has turned it into something of an art. It is no coincidence that one of the most important academic works on the subject, “States of Denial” (2001) by the sociologist Stanley Cohen, was inspired by his experiences as a human rights activist in Israel during the First Intifada in the late 1980s.

Drawing on those experiences, Cohen describes a repertoire of denial employed by both states and societies: “it did not happen” (we didn’t torture anyone); “what happened is something else” (this wasn’t torture, but “moderate physical pressure”); “there was no alternative” (the “ticking bomb” made torture a necessary evil).

In Israel, this logic is rooted in the “purity of arms” myth (the belief that Israel acts only out of self defense) and the age-old “shooting and crying” mentality (the notion that Israelis may commit violence but remain uniquely moral because they grieve over it afterward). But as abhorrent as this mindset may be, it nonetheless rests on two important assumptions: that atrocities like torture, the killing of civilians, and forced displacement are essentially wrong, and thus require justification or concealment; and that the documentation and exposure of the truth has value — even if only as an obstacle to be evaded.

For all its repulsion, the hypocrisy inherent in the “purity of arms” myth has its uses: it leaves room, however narrow, for correction. Once the gap between rhetoric and reality is exposed, it can provoke embarrassment and even generate pressure for change. In such a world, images captured on a phone and shared instantly carry genuine weight.

But this is not the world we live in today. In Israel, the instinct to dismiss any documentation from Gaza as “fake” has been absorbed into mainstream discourse, from the highest echelons of political power down to anonymous commenters on news sites. This reflex is rooted in a conspiratorial mindset imported from right-wing circles in the United States, much like President Donald Trump’s “deep state” rhetoric that has become a favorite of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and his supporters.

One of the chief evangelists of this style of denial is fringe right-wing media figure Alex Jones. In 2012, the longtime Trump ally claimed that the Sandy Hook Elementary school shooting, in which 20 students and six adults were murdered, was staged. Despite overwhelming evidence, Jones insisted that all footage of the massacre — grieving parents, even the bodies of the victims — was faked, all part of a Democratic conspiracy to undermine Americans’ right to bear arms.

This type of discourse began seeping into Israeli society even before October 7, first online and later in formal arenas. As the war has dragged on, it has become a widespread, often reflexive response: A video of Palestinian parents cradling the body of an infant? “Actors holding a doll.” Photos of civilians shot by Israeli soldiers? “AI-generated, manipulated, or taken somewhere else.” And so on, ad infinitum.

This rhetoric has often been paired with the term “Pallywood” — a portmanteau of “Palestinian Hollywood.” Imported from U.S. right-wing circles in the early 2000s, it suggests that images of Palestinian suffering are not real at all, but part of an elaborate movie industry: a vast conspiracy in which Palestinians, human rights organizations, and the international media collaborate to fabricate atrocities.

In an earlier era of atrocity denial, the claims of staging were at least elaborate. Many still recall the case of Muhammad Al-Durrah, the 12-year-old boy killed in Gaza in September 2000, whose death became a symbol of the Second Intifada. Israelis and their supporters invested enormous effort to try to discredit the footage: hundreds of hours of analysis, reports, and even documentaries, parsing shooting angles, ballistics, and forensic details to argue the entire event had been staged.

Today, denial requires no such labor. The intricate conspiracy theories of the past have given way to a cruder form of denialism that scholars call conspiracism — the reflexive dismissal of any evidence that contradicts one’s interests as fabricated. Documentation is simply dismissed with a single word: “Fake.”

Post-truth, post shame

Take, for example, the undeniable evidence of mass starvation in Gaza. The logic is painfully simple: a population kept under siege, and whose entire means of self-sufficiency has been destroyed, will inevitably starve. Yet in Israel, from anonymous commenters online to the highest levels of government, the reflexive response remains the same: “It’s all fake.”

Netanyahu has spoken of the “perception of a humanitarian crisis,” supposedly created by “staged or well-manipulated photos” distributed by Hamas. Foreign Minister Gideon Sa’ar dismissed images of emaciated children as “virtual reality,” citing as proof the presence of “well-fed” adults beside them. The army claimed Hamas was recycling images of Yemeni children or fabricating AI-generated fakes. Ynet journalist Itamar Eichner, otherwise sharply critical of the government, echoed the same sentiment: “They [Palestinians] understand that photos of starved children are a soft spot. The photos are likely staged, and the children could be sick with other diseases.”

This pattern of denial surfaces even in academic discourse. A recent report from the Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies at Bar-Ilan University, “Debunking the Genocide Allegations: A Reexamination of the Israel-Hamas War (2023-2025),” included a section titled “Fake Sources and Others Generated by AI.”

Although documented proof of atrocities has always been met with evasions and denials, the situation today is wholly different. In the “post-truth” era, a combination of heightened suspicion of AI manipulation, the erosion of trust in institutional media, and the collapse of democratic gatekeepers has made the instinct to cry “fake” at anything unwelcome far more widespread and powerful than ever before.

Meanwhile, the reprehensible refusal by the vast majority of the Israeli media to show what is actually happening in Gaza means that when images do manage to slip through, the public response is often little more than a collective shrug of dismissal. Yet almost every time, that shrug is accompanied by “they deserved it,” as denial and justification intertwine in what may seem like a paradox but actually reflects two sides of the same coin.

As Heritage Minister Amichai Eliyahu recently declared: “There is no famine in Gaza, and when they show you pictures of starving children, look closely — you’ll always see a fat one next to them, eating just fine. This is a staged campaign.” In the very same interview, he added: “There is no nation that feeds its enemies. Have we lost our minds? The day they return the hostages — there will be no hunger there. The day they kill the Hamas terrorists — there will be no hunger.”

After two decades of siege, during which we Israelis tried to push Gaza and its 2 million Palestinian residents out of sight and mind, the massacre of October 7 brutally forced back into view what we had sought to forget. Perhaps it was then that the two responses — “fake” and “they deserved it” — fully converged. The first serves the national self-image (“our children are not committing atrocities”) and the demands of hasbara, buying time on the international stage. The second is a raw, visceral reaction to the pain and humiliation of being struck by those long cast as inferior. Together, they fuse into a reaction that overrides any appeal to morality, requires no pause, and demands no apology.

And herein lies the second challenge to the belief that smartphones and social networks can stop atrocities. The struggle for human rights has long assumed that documenting abuses would “shame” perpetrators into changing their behavior. But what happens when perpetrators no longer feel shame, and openly disregard moral censure and even the very idea of truth? In that case, documentation and distribution, however rapid or widespread, lose their power.

Indeed, as human rights reports and international court petitions over the past two years have shown, Israeli military, political, and cultural leaders now admit openly — and of their own accord — what in other circumstances human rights groups would have labored painstakingly to prove.

After decades of denying the Nakba, even banning the term itself, Israeli lawmakers now proudly declare that Israel is carrying out a second Nakba in Gaza. Where once B’Tselem volunteers had to painstakingly film atrocities in the West Bank, only to be met with one excuse or another, such as that the incidents were “taken out of context,” today Israeli soldiers themselves record violations of human rights and upload them to social media without hesitation.

What we are witnessing is the collapse of the traditional cycle of exposure, denial, and confirmation. In such a reality, what use are smartphones and social media?

Cracks in the wall

While the benefit of documenting atrocities is much lesser than we had hoped for in the past, it is still significant. As I write this, it seems as if the reflexive “fake” and “they deserved it” responses are finally hitting solid barriers.

Faced with the vast and relentless evidence of starvation in Gaza, the cries of “fake” are becoming more and more frenzied and desperate. The vicious allegation, endlessly repeated in Israeli discourse, that a Gazan child suffering from a pre-existing illness somehow absolves Israel of responsibility for starving them to death has, apparently, failed to halt the growing acknowledgment in Israel of Palestinian suffering, and of its fundamental injustice.

The twists and turns now common in Israeli arguments — that there is indeed starvation in Gaza but Hamas is to blame; that it is an unintended consequence of war; or that the world is hypocritical for not treating starvation in Yemen the same way — all return us to the repertoire of denials Stanley Cohen described. Yet they also suggest something else: the hesitant reappearance of embarrassment, and perhaps even shame, among at least some segments of the Israeli population.

We remind our readers that publication of articles on our site does not mean that we agree with what is written. Our policy is to publish anything which we consider of interest, so as to assist our readers in forming their opinions. Sometimes we even publish articles with which we totally disagree, since we believe it is important for our readers to be informed on as wide a spectrum of views as possible.