16 August 2018

As the tenth anniversary of the onset of the 2008 global financial crisis approaches, the ongoing turmoil engulfing the Turkish lira sounds the warning bell that all the conditions that produced the crash remain.

In fact, the very measures undertaken by the governments and central banks of the major capitalist countries in response to the meltdown have exacerbated them. This has set the stage for the eruption of another financial disaster, potentially even more significant than that of a decade ago.

The injection of trillions of dollars into global financial markets and the accompanying ultra-low interest rate regime, which produced a bonanza for the very finance houses whose speculative activities set off the collapse, has built a new financial house of cards.

But to an extent hardly imaginable in 2008, all the world’s leading economies are locked in a perpetually escalating cycle of economic warfare. This global trade war is spearheaded by the Trump White House, which sees trade sanctions and tariffs, such as the onslaught it launched against Turkey, as an integral component of its drive to secure the United States’ geopolitical and economic interests at the expense of friend and foe alike.

The character of world economy has undergone a major transformation in the past decade in which economic growth, to the extent it that it occurs, is not driven by the development of production and new investments but by the flow of money from one source of speculative and parasitic activity to the next.

Accordingly, money has poured into so-called emerging markets, such as Turkey, where the prospect of higher rates of return and faster rates of growth resulting from the ability of governments and corporations to take out dollar-denominated and other foreign currency loans at very cheap rates has provided the opportunity for quick profits.

The size of this flood of money is indicated by figures compiled by the Institute of International Finance. According to its data, the combined indebtedness of 30 large emerging markets rose from 163 percent of gross domestic product at the end of 2011 to 211 percent in the first quarter of this year. In money terms that amounted to an increase of $40 trillion in the debts of emerging market economies.

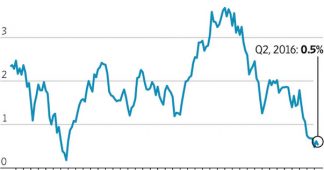

So long as interest rates and the value of the US dollar remained low, this process could continue. But the move by the US Federal Reserve to lift interest rates and end its program of “quantitative easing,” and the consequent upward movement of the dollar, means that the debt burden of dollar-denominated loans rapidly increases. This has produced a rush for the exits which has seen the value of the Turkish lira plunge by as much as 40 percent this year.

But the Turkish crisis is only the most vivid expression, so far, of a much more widespread development. The South African rand has fallen by as much as 10 percent, the Brazilian real has been under downward pressure all this year and this week the Indian rupee dropped to its lowest level in history against the US dollar. With the eruption of the Turkish crisis, Argentina, which in June sought emergency assistance from the International Monetary Fund to try to halt the plunge in the peso, lifted its central bank interest rate by 5 percentage points to 45 percent in order to try to stop the financial haemorrhaging.

The turmoil in emerging market economies bears a striking resemblance to the Asian financial crisis of 1997–98 when the collapse of the Thai baht set off a plunge in currencies across the region. Described by US President Bill Clinton as a mere “glitch” on the road to globalisation, the Asian crisis resulted in a deep recession across the region. It led in turn to a crisis of the Russian rouble which played a central role in the collapse of the US investment fund Long Term Capital Management, which was bailed out by the New York Federal Reserve amid fears that its failure would spark a crisis of the entire US financial system.

Likewise, all the ingredients for the spread of “contagion” from Turkey and other emerging markets are present in the current situation but at a more advanced level with major European banks having provided hundreds of billions of dollars in loans.

But while there are similarities with earlier crises, there are also major differences. These relate to the geo-political environment, which today is characterised above all by the disintegration of all the post-war arrangements and mechanisms whereby the major powers came together to seek to regulate and contain the economic contradictions of the system over which they preside.

Last June, the meeting of the G7 group of major powers broke up in acrimony over the tariff and trade war measures initiated by the US, despite the continuing pledges since 2008 to never again carry out the beggar-thy-neighbour policies that led to the Great Depression.

Less than three months later, the consequences of this breakdown can be clearly seen. It is highly significant that the immediate spark for the lira crisis was the decision by the Trump administration to double the steel tariffs imposed on Turkey in an effort to subordinate it to its foreign policy and military objectives in the Middle East. As has been widely noted, in previous crises the US, in collaboration with other major powers, would have intervened to try to calm the situation.

But this has gone by the board under the “America First” agenda of the US administration. The US would have known the consequences of its Turkey intervention for European banks that had heavily invested in the country. But as far as Washington was concerned this may well have been regarded as an additional benefit under conditions where Trump has characterised Europe as a “foe” so far as economic relations are concerned.

The rise of trade war is not confined to the US. With the breakdown of the mechanisms of post-war economic and financial regulation, every major power is looking to its own interests, leading to the escalation of economic warfare and ultimately to military conflict. The contradiction between the global economy and the division of the world into rival nation-states and great powers is assuming ever-more tangible forms.

Excerpt from an article at wsws.org