Growth and the euro after Brexit: neo-liberal colonialism for the eurozone

by Alexander Ulrich & Steffen Stierle

In the summer of 2015, five EU presidents – the Presidents of the EU Commission, the European Council, the Eurogroup, the European Central Bank and the EU Parliament – presented a report entitled Completing Europe’s Economic and Monetary Union. In the report they outline a sweeping reform agenda in the areas of economic, financial and fiscal policy. Some of this has already been set in motion. Its full implementation, however, has been thwarted, both by the German Government’s reluctance to give up power and by fear of the referendums which would have been unavoidable in view of the need to amend the treaties.

On 20 September 2016, the Jacques Delors Institute in Berlin/ Notre Europe and the Bertelsmann Foundation presented a report entitled Growth and the Euro after Brexit. Back in February 2016, Norbert Häring, economics correspondent of the Handelsblatt newspaper, was already writing, “Now that the five presidents’ de-democratisation project has foundered, presumably on Berlin’s insistence on its position of power in Europe, a new group of exports will now be appointed to draft a blueprint for political and fiscal union. Needless to say, it will not operate as a convention of European people’s representatives or the like but will do its work in the shadowy world of ‘pro-European’ foundations and think-tanks.” (here in German)

On the content of the report

Pressed into service once again as the main legitimising factor for another drive towards deeper union is the glorious 60-year history of European integration, which must be continued. Since this rather emotionally focused line of argument is wearing thin after years of the Troika’s impoverishment policy, another element has been added to it, namely fear of the next crisis. This, according to the report, is inevitable, the only question being when it will hit. The time that has been bought should be used to implement fundamental reforms; the report proposes that these should comprise three building blocks – a first-aid kit, a convergence and growth package and the establishment of a true economic and monetary union.

First aid for the eurozone

The core of the first building block is the development of the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) into an ESM+. This upgraded mechanism is to have at its disposal a 200-billion-euro rapid-response facility, which it can use as it sees fit. Until now, every rescue loan and every associated Troika programme has had to be approved separately by the Member States. In Germany and some other countries, parliamentary approval is even required. This would no longer be the case in future. The ESM would be given a blank cheque and, free from any democratic scrutiny, would be able to force more and more austerity programmes on countries in crisis.

The report also deals with banking union as part of this first building block. The emphasis is on common deposit insurance and on the idea of refinancing banks directly in future through the ESM. The idea that taxpayers should no longer be required to bail out banks is evidently just as unappealing to the Delors Institute and the Bertelsmann Foundation as it is to ECB President Mario Draghi and to the Italian Government, which is currently seeking a solution to the imminent banking crisis. On the contrary, taxpayers in the EU are supposed to step into the breach together whenever a major bank has gambled away its assets and is in trouble.

Lastly, the first-aid kit involves stricter interpretation of rules, such as those of the Stability Pact. More penalties, allegedly, are needed. Those with excessive debts would have to make more penalty payments in future, which would further increase their indebtedness and further diminish their prospects of economic recovery.

Convergence and growth policy

The logic underlying the second building block is that of combining structural reforms with investments – a logic of give and take on which the five presidents’ report was also based. As far as structural reforms are concerned, importance is attached to prioritising the reforms with the greatest impact. This primarily means more deregulation of the market in services and of the labour market. Nothing new here.

On the other hand, the private and public investment gap is acknowledged. One of the ways in which it is to be closed is through more incentives for cross-border investment. To this end, firms are to receive better incentives to invest abroad. How this is supposed to be done is not explained. The line of argument, however, is highly reminiscent of the controversial investors’ rights to sue governments that are set to be established through the TTIP and CETA.

At the same time, international flows of capital are to be facilitated. This is essentially to be achieved by pursuing the Capital Markets Union proposed by the five presidents, a union based on harmonised financial (de-)regulation and in particular on securitisations, in other words on the very instrument in which the great crisis had its roots in the United States in 2007.

To mobilise private investments, moreover, public treasuries are to fund the high-risk parts of projects. The motto seems to be ‘privatise profits and nationalise risks’.

Risk and sovereignty sharing

The third building block is designed for the long term and relates to the question of finality. The first two blocks are regarded as stages on the way. According to the report, both risks and sovereignty are to be shared in the long term.

The nucleus of this vision is the development of ESM+ into a European Monetary Fund (EMF). This fund would be allocated a flexible budget amounting to about 10% of the total eurozone GDP and be used to organise successive transfers of sovereignty from the national to the EU level. This is how it works: In the future, countries with unsustainable debt ratios would be able to issue more bonds exclusively through the EMF. In return, however, they would have to accept more stringent reform requirements and grant the EMF an absolute right to veto the national budget. The final word on a country’s political agenda would no longer rest with its national parliament but with a new, very powerful EU institution.

The boss of this institution would definitively be one of the most powerful people in the EU: A Euro Finance Minister, who would head the EMF and chair the related negotiations as well as being an EU Commissioner and heading an Ecofin Council with increased powers. Maybe even Mario Draghi could become jealous. With this job, one can torpedo hole national budget plans and force deficit countries in one austerity program after the other.

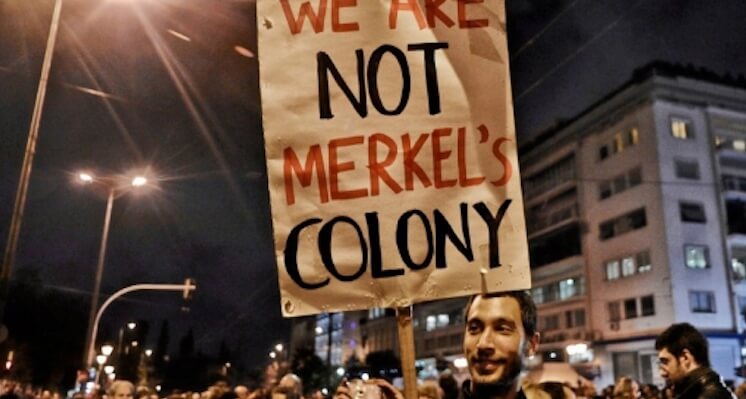

In addition, it is proposed that “the focus should no longer lie on managing crises, but on preventing them”. Sounds good. The reforms that are outlined as a means to this end, however, are tantamount to a radicalisation of the existing Troikapolicy of recession and impoverishment which public debts have been used to enforce. All those who have previously hesitated to refer to EU crisis-management policy as colonialist can shed their inhibitions:

“It would allow Member States to temporarily transfer debt that exceeds 60 percent of GDP once, and once only, to a European fund. Redemption, however, comes at a price: Member States are required to maintain a primary surplus over the redemption period of up to 30 years.”

To put it in a nutshell, being broke once brings 30 years of austerity. Democracy would be largely suspended for the duration of that period. Any alternative to the neo-liberal policy of cutbacks would be inadmissible.

Concluding assessment

The original report produced by the five presidents was an attempt by the EU elite to map out a neo-liberal route to deeper union that could represent a compromise among the governments and especially between those of France and Germany. The report under examination here pursues this quest for compromise but radicalises both sides of the equation. On the one hand, it goes a long way to satisfy the French desire for risk-sharing, in that taxpayers of all euro countries would be jointly liable for the failure of individual banks. On the other hand, it seeks massive long-term transfers of fiscal sovereignty to the eurozone without proposing the establishment of any significant democratic oversight.

Germany’s power as the largest creditor state would increase considerably in the long run, as would that of major supranational financial institutions. National parliaments and the European Parliament face the threat of another giant step towards insignificance.

It is noticeable that the report stresses time and again that this, that or the other will not require an amendment of the EU treaties. Quite obviously, this is partly an attempt to remedy a major weakness in the five presidents’ strategy, namely the need for amendments to the treaties, which would have had to be ratified in all Member States, in some cases by referendum. This requirement has hitherto been a source of reassurance. The Greek oxi of July 2015, the Dutch nee to the Association Agreement with Ukraine and the Brexit vote show that the populations of Europe can be relied on to resist further socially unjust and undemocratic projects for deeper European Union. Now the Europeanist think-tanks are evidently working hard to find ways of bypassing these populations. They appear to be content with their progress so far, as reflected in this report.

While the report generally considers it prudent to lend democratic legitimacy to the whole structure, it does not contain any indications as to the form that this legitimisation might take. There are references in places to a primary reliance on interparliamentary bodies such as the conference established by Article 13 of the Fiscal Compact, in other words on weak and malfunctioning interparliamentary talking shops with no decision-making powers, created for the sole purpose of feigning democratic legitimacy without giving any real political influence to the people’s elected representatives.

It remains to be seen how much impact this report will have in practice. Here we turn again to Norbert Häring, who wrote, “There has already been a think-tank of this kind, which was led at that time by the Jacques Delors Institute in Paris, the parent body of the Berlin institute. […] In 2012 that working party produced the report called Completing the Euro, and it is no coincidence that its report reads like the first draft of the later four presidents’ report on the future development of monetary union and of the even later five presidents’ report. Much of their content has already been implemented with modifications. It is clear to see that it was the experts who mapped out the path taken by the euro area.” The paper, then, should not be underestimated just because it was not published by an EU institution or a similar official body.

We can be sure that many of the proposals will soon be cropping up in the official agenda of the European Union. German minister of finance, Wolfgang Schäuble kicked already off this process in early October, when he proposed to transfer the competition of budget surveillance to the ESM. Taking the word of Bertelsmann/Delors he clarified, that this would not require changes in the EU treaties, but only modification of the ESM treaty.