On the European Pillar of Social Rights

by Steffen Stierle

May 13, 2017

At the end of April the EU Commission unveiled its package on the social dimension of Europe to a great fanfare. President Juncker had already in advance declared the European Pillar of Social Rights to be a top priority, demanding a social triple-A for the EU and calling it possibly “the last chance to reconcile the EU again with its citizens”. After years of the troika–imposed social cuts, tax-funded bank bailouts and attacks by the ECJ on workers’ rights, one cannot help but wonder what this change of direction towards a social Europe is supposed to look like. So what is in this package?

The 20 Principles of the Social Pillar

Firstly there are the twenty principles of equal opportunities, working conditions and social protection. At first glance the list looks ambitious: women and men are to be entitled to equal and fair pay, parents are to have the right to suitable leaves of absence, workers will have the right to good health protection, appropriate social protection and later on, to adequate pensions, etc.

There is, therefore, much talk about rights. This suggests that EU citizens are to have entitlements which they, if it comes down to it, could claim. But a policy paper published on the Commission’s website is not yet European law. The principles are more like a set of non-binding recommendations to Member States or merely paying lip service.

It might be argued that the formulation of the principles is just the start and that they will then gradually have to be translated into acts of law. That is in part already happening, as set out in the following section. Yet the way the principles are formulated means that little would be achieved: wages, social protection, pensions and much more are to be appropriate, fair or at a high level – elastic terms which are subject to a wide degree of interpretation. The Commission draws up its draft legislation to all intents and purposes outside democratic control and generally subject to the strong influence of the commercial and financial lobbies. These for their part are likely to have a very different understanding of what constitutes appropriate or fair than the average EU citizen.

Directives on Parental Leave and Obligation to Provide Information

Beyond these relatively meaningless principles the Social Pillar contains a few initiatives for specific acts of law. Thus the Commission is preparing a directive on work-life balance which is in essence a renaming of the long-planned directive on parental leave. A couple of extra days off for new fathers should do it. But there’s not much more beyond that. Furthermore the Commission proposes a hearings with the social partners in order to revise the written statement initiative from 1991. This revision could give employees the right to receive a written list of the conditions of employment applying to them. While there is certainly nothing wrong in this, it does little to actually change poor working conditions.

To make it complete, there are vague announcements that the Commission will provide some guidance on how to interpret the working time directive from 2003 and for a social partner consultation regarding workers access to social protection. However, these points seem not to be intended to end up in binding law.

So beyond very few minor points, the translation of the principles into legal acts is left to the future without any concrete timetable being laid down. Viewed dispassionately the Commission with this package shows itself to be completely unable or unwilling to enforce genuine social rights for its citizens. Social and Europe apparently do not belong together, that is to say, for as long as Europe means the EU as it is today and the EU is defined by its institutions such as the Commission and the ECJ and the treaties on which its actions are based. What is meant by social in this context can be seen in a further document from the Social Pillar package, referred to as a reflection paper.

Reflection Paper on the Social Dimension of Europe

In this document the Commission sets out three scenarios which describe ways European integration could be shaped in the future and what that means in each case for its social dimension. None of the scenarios describes the way to a true social EU, that is to say an EU which protects people from the harshness of the market by creating and defending de-commodified areas, for example by providing important basic public services and an effective universal social insurance system.

More informative than the abstract scenarios are the comments on “today’s social realities” and the “drivers of change by 2025”. Here the Commission fosters a definition of the social which probably corresponds to only a very limited extent with the ideas of most citizens and which ultimately applies in one way or another in each of the scenarios.

Firstly, the choice of indicators to describe today’s realities is noteworthy. The Social Pillar also contains what is referred to as a social scoreboard which brings together the indicators that are to be used to assess social developments. The Commission’s analysis is that while “the crisis has had a marked effect on many Europeans who had to cope with flat or falling incomes” (which is a gross understatement of – in some cases – dramatic falls in income, as a closer look at the countries hit hard by the crisis would have shown), the situation as a whole in the global context remains good. Employment rates, it says, are rising, many new jobs have been created in the service sector, youth unemployment has fallen and things are looking better as far as gender equality is concerned.

Yet the analysis fails to mention rapidly declining pensions and social benefits in crisis-stricken countries, the unbelievably high level at which youth unemployment stood before falling slightly, the massive rise in homelessness, the many private bankruptcies and the sometimes precarious access to vital health services etc., to say nothing of the question of remuneration and the quality of the jobs created in recent years.

The particular selection of indicators therefore glosses over the real situation. Yet even the Commission cannot avoid determining that since 2010 “there has been an increase of 1.7 million people at risk of poverty”. Considering the fact that poverty in the EU is measured in relation to a country’s average income, which plummeted dramatically in many EU Member States during the crisis, this figure is likely to significantly understate the reality in the crisis-stricken EU.

The EU Commission’s New Social Idea

On the basis of this rather laid-back description of the situation, the paper addresses the social challenges of the future and possible solutions, taking 2025 as the reference date. In its social scenario the Commission effectively develops a neoliberal definition of the social. This on the one hand follows the long tradition of shifting the discourse in a neoliberal direction, and on the other hand distances itself significantly from traditional ideas of the social, at the same time preparing the ground to enable this definition to play an important role in future day-to-day politics.

There is much talk at the beginning of the challenges of an ageing society. The scale of demographic change, however, is greatly exaggerated, while at the same time increases in productivity and the rising employment rate (which had been strongly highlighted before) and the accompanying improvement in the performance of pension systems are downplayed. The only solution offered is an adjustment of the pension age. An increase in pension age – a de facto pension cut (particularly in times of high unemployment and an ageing workforce) – which are generally understood to signify falling social standards, are turned into the opposite.

There is also discussion of shortages of labour, which given the extraordinarily high levels of unemployment which still persist, flies in the face of reality. The solution offered: more migration into the labour markets. Work mobility is to be increased so that it is easier for jobs and workers to find each other. A study of what is already happening in practice reveals where this ends up: skilled workers from regions beset by crisis migrate to economically stronger regions to find work. This means that the weak regions lack the skilled workers needed to revive the economy while in stronger regions competition for higher skilled jobs and hence pressure on wages increases. Along the way close social relations and family structures providing solidarity are destroyed, to be replaced by loose urban networks.

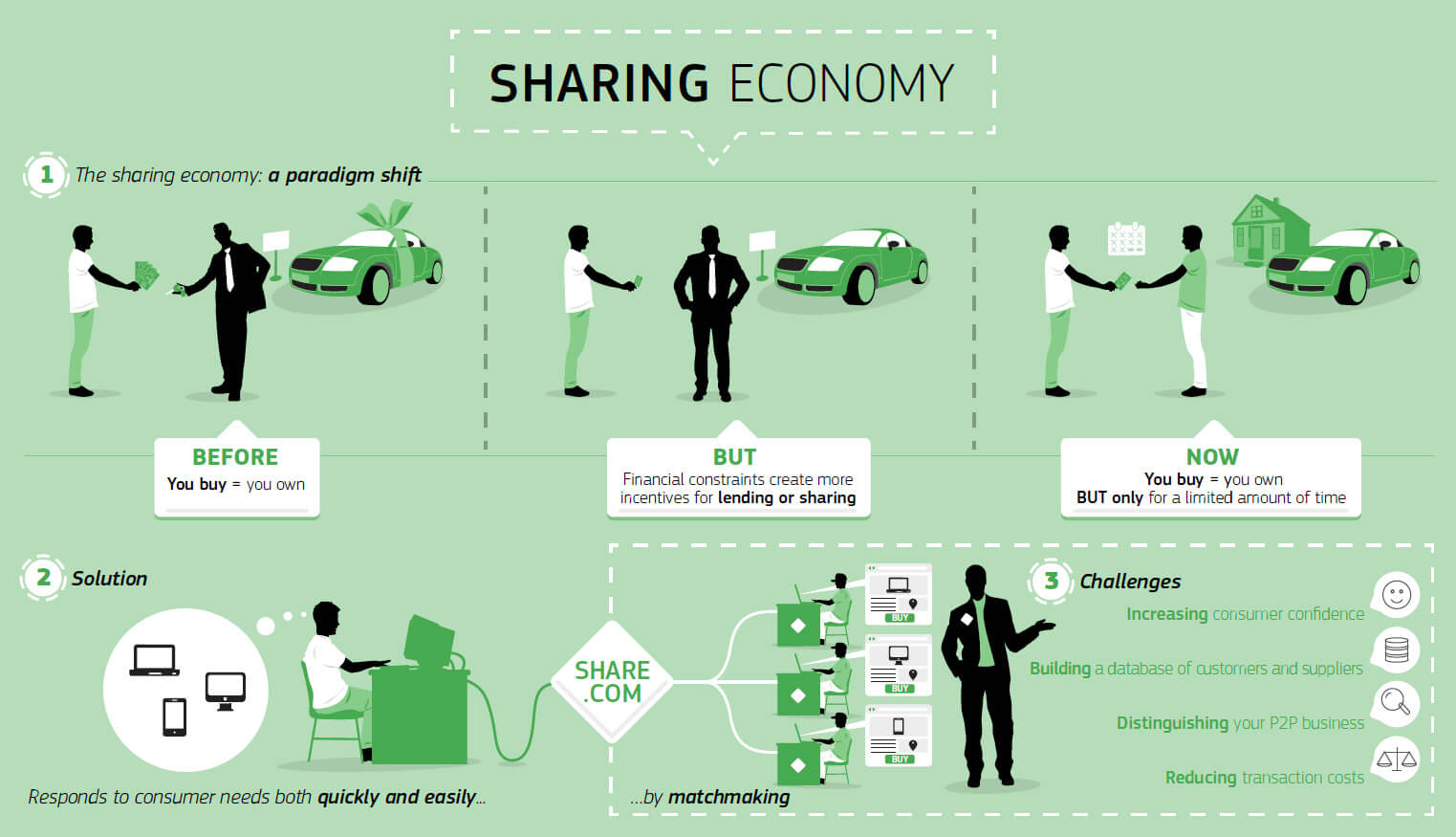

The Commission goes on to state that: “In the space of a generation or two, the average European worker may have gone from having a job for life to having up to ten jobs in a career”. But even today a job for life is more the exception than the rule. What the Commission describes is the rapid increase in the number of fixed-term jobs, temporary jobs, project-related appointments, mini jobs etc. Instead of seeking to put the brakes on this development towards increasingly atypical, insecure unemployment through better protection against dismissal, limits on temporary work and other political measures, it praises this “trend towards the flexibility of workers” and the “opportunities for people to work as free-lancers and combine several jobs at the same time”.

The social answers the Commission offers are aimed at preparing the EU citizens better for this permanent uncertainty, for example by modernizing education systems. Giving people certainty to plan their lives disappears from the agenda of social policies. It is taken for granted that EU citizens will submit to the flexible needs of the economy. Social Europe is designed not to protect people but to help them become more flexible and hence better equipped to subordinate themselves under market requirements.

Seen in this context the lament about falling birth rates is also noteworthy. These are rightly seen as a problem. It is also right to say that further progress in terms of gender equality and better childcare services could help. But such measures fail to tackle the crux of the problem, namely the extreme economic insecurity experienced by many families. It is obvious and confirmed by several studies that many people are deterred from having children because they are afraid of falling into poverty, dragging their children down with them. To increase birth rates, what is needed is not more flexibility but rather secure working conditions and seamless social protection systems. Such approaches, however, play no part in the Commission’s reflections. Increased work mobility is also unlikely to be helpful in this respect.

There are many other examples in the reflection paper which could be listed here, but the overall picture is the same: as social Europe the Commission constructs a problem and a solution in which social cutbacks are declared social policy. There is no endeavour to protect people from the rigours of the market. What they can expect at best is to be better prepared for a life as a commodity on the labour market.

The approach ultimately is to shape the idea of social Europe in such a way that it can be incorporated without problem into the neoliberal Europe. Yet what is neoliberal cannot be social. Neoliberalism subjugates people to the markets and the powerful players. Social policy deserves its name only if it aims to protect people from the markets which dominate them, that is to say when it is anti-neoliberal.

Martin Höpner is right when he argues in a Makroskop article (in German) that the consequence to be drawn is to better protect social policy at national level from attacks at EU level and to put greater effort into finding other, more flexible forms of international cooperation. He is also right to call for a de-ideologisation of the discourse about social Europe. The Commission’s package clearly shows that – as long as Europe is synonymous with the present-day EU – a social Europe is wishful thinking; it shows that nothing is achieved that deserves to be called social.