By Gabriel Hetland

According to The New York Times, Venezuela is “a country that is in a state of total collapse,” with shuttered government offices, widespread hunger, and failing hospitals that resemble “hell on earth.” There is reportedly “often little traffic in Caracas simply because so few people, either for lack of money or work, are going out.” The Washington Post, which has repeatedly called for foreign intervention against Venezuela, describes the country using similar, at times identical, language of “collapse,” “catastrophe,” “complete disaster,” and “failed state.” A recent Post article describes a “McDonald’s, empty of customers because runaway inflation means a Happy Meal costs nearly a third of an average monthly wage.” NPRreports “Venezuela is Running Out of Beer Amid Severe Economic Crisis”. When Coca-Cola announced plans to halt production due to a lack of sugar,Forbes dubbed Venezuela “the Country With No Coke.” The Wall Street Journal reports on fears that people will “die of hunger.”

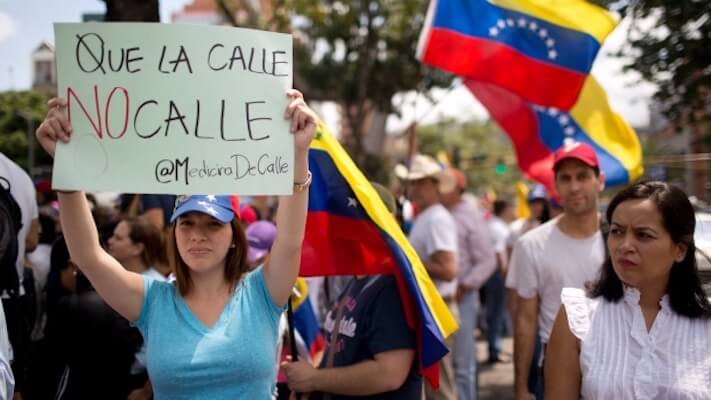

Is Venezuela descending into a nightmarish scenario, as these stories suggest? To answer this question I’ve spent the last three weeks talking to dozens of people—rich and poor, Chavista and opposition, urban and rural—across Venezuela. My investigation leaves little doubt that Venezuela is in the midst of a severe crisis, characterized by triple-digit inflation, scarcities of basic goods, widespread changes in food-consumption patterns, and mounting social and political discontent. Yet mainstream media have consistently misrepresented and significantly exaggerated the severity of the crisis. It’s real and should by no means be minimized, but Venezuela is not in a state of cataclysmic collapse.

Accounts suggesting otherwise are not only inaccurate but also dangerous, insofar as they prepare the ground for foreign intervention. This week the Permanent Council of the Organization of American States is holding an emergency meeting to consider OAS Secretary General Luis Almagro’s invocation of the Inter-American Democratic Charter against Venezuela. This action is taken against countries that have experienced an “unconstitutional alteration of the constitutional regime that seriously impairs the democratic order in a member state,” and can lead to a country’s suspension from the OAS. The Venezuelan government, which despite some foot-dragging has allowed steps toward holding a recall referendum against President Nicolás Maduro, vigorously rejects this charge, as do many OAS member states. It is worth noting that the OAS has not invoked the Democratic Charter against Brazil, which recently experienced what many OAS member states and prominent Latin American observers see as a coup.

In Caracas, the streets are crowded, the metro is working, and free public-health clinics are functioning normally.

APOCALYPSE NOW?

Within days of my arrival to Caracas a few weeks ago it became clear that while life in Venezuela is far from normal, and many are suffering from the crisis, mainstream media images of a country in utter disarray are clearly overstated. Far from being empty, Caracas’s streets and highways exhibit the same pattern of heavy car and foot traffic found in other large Latin American cities. The metro feels as crowded as ever. Restaurants in the affluent neighborhood of Las Mercedes are jam-packed and have been for weeks, according to friends who live in the neighborhood. The shelves of private supermarkets in Las Mercedes and other affluent neighborhoods are full, with plentiful chicken, cheese, and fresh produce. The Wendy’s down the block from the apartment I’m staying in has been full most times I’ve passed it, including on a rainy Sunday night when a steady stream of customers passed through. Beer has not disappeared (and will be available for at least the rest of this year). And I’ve even had multiple Coca-Cola sightings.

There are other signs Venezuela is not “in a state of total collapse.” No one I’ve spoken to has positive things to say about public hospitals, which are seen as corrupt, understaffed, and lacking supplies, which hospital staff allegedly steal and resell. Yet, I’ve heard abundant praise for, and more measured critiques of, free public health clinics (Centro Diagnóstico Integral, or CDIs) and physical therapy centers (Salas de Rehabilitación Integral, or SRIs), which are open throughout Caracas and in cities in the interior. Several opposition supporters from Petare, one of the largest barrios in Latin America, told me of a CDI they go to “that provides a really great service.” I visited a sparkling-clean SRI in Carora, a city of 100,000 in the central-western state of Lara. The center (one of four in the city, all of which are open) treats 80 to 100 patients a day, and I was told all machines were in working order. Ramón Suárez, a backup Lara state assemblyperson for the ruling United Socialist Party of Venezuela (PSUV), has been receiving near-daily treatment at this SRI since suffering a hand injury in December. He told me, “Without the SRI I couldn’t have recovered,” explaining that treatment in private clinics costs 3,000-4,000 bolivares a visit. This would have consumed almost all of Suárez’s salary of 80,000 bolivares/month, which is almost triple the minimum wage (approximately 15,000 bolivares/month plus 18,000 bolivares in food tickets).

The Times’s assertion that “huge areas of the country have spent months with little” electricity is belied by the facts. In April the government took a series of measures to combat an electricity crisis, caused by Venezuela’sworst drought in 47 years, and extremely low electricity rates, which led Venezuela to have the region’s highest per capita electricity consumption. To restore water levels in the Guri dam, which supplies roughly 70 percent of Venezuela’s power, the Maduro administration closed select government offices for one, and then three, days a week; closed schools on Fridays; and rationed electricity in most the country outside Caracas. As of last week, government offices are again open five days a week, albeit on a reduced schedule (8 am-1 pm). Schools are again open on Fridays. Electricity rationing, which occurs for three hours a day on a rotating schedule in interior states (meaning electricity is and has been available for twenty-one hours a day in these areas), remains in effect during the week but no longer on weekends, and may soon end altogether. The government says these recent changes (which bring Venezuela back to a state of semi-normalcy when it comes to electricity) are possible because of the success of rationing, which, alongside recent rains, has allowed water levels in the Guri dam to return to near-normal levels.

“THE SITUATION IS HARD”

Venezuela is not “hell on earth,” but there is no denying that many Venezuelans are suffering right now, something top government officials have been far too reticent and slow in acknowledging. “The situation is hard, and it’s gotten worse over the last two years,” says Jesus Rojas, a teacher and father of two from the small town of Río Tocuyo (population 7,000) in Lara state. “It’s hitting families especially hard. It’s not easy to get food, and what you can get is at very high prices. You’ve seen the long lines [at stores selling price-controlled goods]. People do have purchasing power; they have money. The problem is that people are selling things at six or seven times the [regulated] price, and there’s no control from the state. That’s the thing that’s bothering people the most.”

Food and basic-good scarcities have grown significantly worse over the last year, in part due to inflation.

Food and basic-good scarcities have been a problem for some time, but have grown significantly worse over the last year, in part due to inflation, which sources close to the government say official figures put at roughly 370 percent over the last twelve months. Everyone I spoke to said it is extremely difficult, and often impossible, to obtain staples such as flour, milk, sugar, oil, and black beans. “The basic diet is not available,” says Atenea Jimenez, a co-founder of the national Red de Comuneros, a grassroots network linking communes throughout the country. Beef and chicken are available but at such high prices many people cannot afford them. “Beef costs 5,000 a kilo,” says Jimenez. “That’s 10,000 for two kilos. If your monthly salary is 20,000, that’s half your salary.” Jimenez and others say the food crisis “has changed what we talk about. Three years ago everyone was talking about this or that decision made by Chávez. Now people are talking about food. Our life is filled with this [search for food].” This makes organizing more difficult. Jimenez says there have been times “we couldn’t have meetings because everyone was busy trying to obtain food.”

The food crisis affects all sectors of the population, but not in the same way. If the packed restaurants and cafes of Las Mercedes are any indication, the very rich are eating better than they ever have. This is likely because of their access to US dollars, which trade for roughly 1,000 bolivares/dollar at the black or “parallel” rate—a hundred times more than the lower of two official exchange rates (10 Bs/dollar), and roughly double a higher exchange rate, which the government has allowed to rise since February, from 200 to 600 Bs/dollar. For middle-class Venezuelans, the food crisis has limited their ability to choose what they eat. According to Ramón Suárez, “People are eating but they’re not eating what they want.” Carlos Gonzalo González, a middle-class radio host from Carora, says, “We can’t find the variety of salads we used to get. We’re eating less meat, because it’s expensive. And we’re eating more carbohydrates, which isn’t healthy.”

The full shelves of a private grocery store in Las Mercedes, a middle-upper class neighborhood of Caracas, June 3.(Gabriel Hetland)

Workers and the poor are the hardest hit. Jesus Rojas says, “There are lines [to buy price-controlled goods] up to a kilometer long, and you don’t know if you’ll get anything if you’re at the end of the line. Some people are eating only once a day or not at all. It’s happened to me,” says Rojas, who estimates that this has affected “twenty or thirty percent” of Río Tocuyo’s residents. In the last year, Rojas has lost 7 kilos. Many others say they and their loved ones have also lost weight recently. Atenea Jimenez says, “A majority of people in the barrios and [her rural hometown in Aragua] are eating just twice a day.” Residents of Petare say the same thing. In addition to an overall reduction in caloric intake, less-affluent sectors of the populationare suffering from marked reductions in protein consumption. Jimenez says, “The situation with meat is dramatic.”

Venezuelans are not experiencing mass starvation, though a small but growing number of families are in critical situations of chronic hunger. Lalo Paez, the director of the Office of Citizenship Participation in Torres municipality, where Carora is based, says five of the 503 families living in his hometown of Los Arangues (20 minutes outside Carora), “are in a critical situation.” Paez recounts seeing “people gnawing on sugar cane” because they have nothing else to eat. He estimates that half the town’s population eats just twice a day. A teenager from Los Arangues told me five of the roughly 50 students in his high school class regularly complain to the teacher about being hungry. Paez links residents’ suffering to scarce employment and little water, which inhibits gardening.

Sicarigua, a town just down the road from Los Arangues, is faring much better. Workers from Hacienda Sicarigua, one of Torres municipality’s largest haciendas, which produces sugarcane and cattle, say, “We’re eating well.” This is due to three factors not present in Los Arangues: regular income for most town residents; a daily allocation of two glasses of milk “for everyone who works on the hacienda”; and access to water from a nearby river, which has allowed local families to cultivate vegetable gardens.

As with food, there are scarcities of many medicines, particularly for more specialized conditions.

Besides food, a key source of anxiety for many Venezuelans is access to medicine. As with food, there are scarcities of many medicines, particularly for more specialized conditions, such as cancer, diabetes, and high blood pressure. These scarcities are due to the country’s lack of sufficient dollars to purchase imports (a problem related to the government’s inability to effectively tackle the currency exchange issue, as well as the plunge in the price of oil over the last two years), and to bachaquerismo, the practice of buying price-controlled food, medicine, and basic goods and reselling on the black market at rates ten to fifty times higher than official prices.

Most people I spoke with were worried about obtaining medicine, but said that they are their families had been able to get access to the medicines they need. Often this takes place through extended family networks spanning the country, and sometimes the globe. Families who can afford to do so rely on bachaqueros as well. Not everyone, however, can find what they need. Rojas says, “It’s very difficult to get medicine for specialized conditions like high blood pressure and diabetes.” For months, Rojas has vainly searched for medicine for his sister’s epilepsy: “I’ve gone everywhere—here [Carora], Barquisimeto, Caracas, Maturín—and I can’t get the medicine.” He added, “My mother is 83 and has high blood pressure, and I can’t get the medicine she needs.”

People waiting in line outside government-run Bicentenario supermarket in Carora, June 4. (Gabriel Hetland)

Over the last few weeks the discontent generated by chronic scarcities has boiled over into acts of looting. On several occasions, people I was speaking to received texts during the conversation alerting them to nearby instances of looting. The first time this occurred was on June 7 in Carora, while I was talking to Myriam Gimenez, a grassroots activist who continues to support Chavismo. Gimenez blamed the looting on the opposition, showing me texts purportedly providing evidence that this was part of a destabilization plot. Gimenez also said, “This is the first time this has occurred here.” On another occasion, several Petare residents I was meeting with received texts suggesting there were “disturbances” occurring at the Palo Verde metro station in Petare. Within a few minutes, one of the women managed to speak to someone in the Palo Verde metro station who said the rumors were false and all was calm there.

The government has lost significant support, but this has not translated into greater support for the opposition.

These examples highlight the growing, generalized sense of anxiety felt by Venezuelans throughout the country. But my firsthand experiences, and daily perusal of Venezuelan newspapers, provide no support for the idea that Venezuela has descended into chaos. Looting is happening, but in a sporadic rather than generalized manner. Yet people are certainly ready to believe looting is occurring, and are not shocked by news of it.

NI UNO, NI OTRO

Everyone I spoke to, regardless of their political beliefs, agrees that the government has lost significant support since the December 6, 2015, legislative elections, which the opposition won handily. There is also widespread agreement that this has not translated into greater support for the opposition. Four opposition activists (two ex-Chavistas) from Maca, a community in Petare, told me “Chavismo has declined 100 percent” in Petare. I asked if this had led to greater support for the opposition. They vehemently shook their heads and replied, “People have not been joining the opposition.” One commented, “People don’t want to hear anything about politics.” Another added, “They’re tired of all the politicking. They just want to eat.” I asked them about criticisms that the opposition has not offered any concrete solutions to the problems facing Venezuela, instead focusing solely on the recall referendum. They nodded vigorously saying, “It’s true. No one is offering any solutions.”

I heard similar sentiments elsewhere. For example, a taxi driver in Carora said he used to support the government but could no longer do so because it has not been able to provide solutions to the crisis. Yet he also criticized the opposition, saying, “We know what they brought [in the past] and it wasn’t good.” I asked him whom he supports. He replied, “Ni uno, ni otro,” neither of the two options.

None of the Chavista activists I spoke to, most of whom I’ve known for years, expressed any support for the opposition. All, however, expressed significant criticisms of Maduro and the government. Jesus Rojas, who has supported the government since Chávez’s 1998 election, said, “Many people don’t believe in Maduro anymore. While we still have hope in the process, we don’t see a short-, medium-, or long-term solution. There’s uncertainty.” Switching to English he added, “There’s no light at the end of the tunnel. We’re fucked.” Despite this, Rojas says he continues to the support Chavismo and the PSUV and will never vote for the opposition. “If I voted for Chávez and against the fourth republic governments [preceding Chávez] that brought us neoliberalism and bad times, it doesn’t make sense to go back to the bad government of the fourth republic.”

“The leadership doesn’t know the anguish and anxiety that people are living with now.”

Atenea Jimenez, the commune leader, is terrified of the opposition, whom she says “will bring fascism and neoliberalism.” She recalls the 2002 coup against Chávez, when she says lists of Chavista activists, allegedly targeted for assassination, circulated. Other Chavistas told me they saw their own names on such lists. (As Gregory Wilpert has reported, there was “a witch hunt for pro-Chávez officials” and community media leaders during the April 2002 coup.) Jimenez continues to support the government but is extremely critical, saying, “The leadership doesn’t know the anguish and anxiety that people are living with now. The leadership acts like we’re still in the same situation we were in three years ago. The majority of people are questioning [the government] and the management of the economy. But when [Chavistas] critique [the government], they are called counter-revolutionaries and pushed aside. The government and the party should allow for a critical current to develop internally [within the PSUV]. If not, the situation will bring the right [to power].” She adds, “The guarimbas [the violent opposition protests of February 2014] didn’t bring down the government, but hunger could.”

Myriam Gimenez is also critical of the government and the PSUV. She says, “My critique is that the party is trying to substitute itself for popular power. The communal councils cannot be an appendix of the party, they have to be the community.” Despite this critique, Gimenez says that charges the government and PSUV always act in a politically discriminatory manner are exaggerated. This allegation has frequently been made regarding a recent government initiative to distribute price-controlled food through Local Provision and Production Committees, or CLAPs. Gimenez has participated in distributing CLAP food bags in Carora and says, “I can say with full security that there is not political discrimination here.” I ask how she can be so certain. She replies, “I’ve participated in this, and the last food distribution I was part of gave bags to the communal council in La Greda, which is run by Adecos [supporters of the opposition Acción Democrática]. And I saw that they gave the correct number of bags of food to the communal council.”

When I asked Gimenez why she continues to support the government, she replied, “Because it’s not a lie that 3 million senior-age Venezuelans are receiving a pension that’s worth minimum wage. When Chávez got to power, not even 300,000 seniors received a pension, and the pension wasn’t even a fifth of the minimum wage. It’s not a lie that schools opened to all children with a meal every day.… It’s not a lie that they opened more opportunities for studying at the university level. And it’s not a lie that education at all levels is free, totally free. Oh, but this education has errors, we don’t doubt it. It’s part of a [process in] construction.… It’s not a lie that healthcare, with all the problems we have right now with the dollar, and the import of medicines…that they’ve provided a space for healthcare in all of our communities. It’s not a lie that our citizens with disabilities, who were rendered totally invisible before, they didn’t have machines to treat their disabilities, now we have physical therapy centers, and today [people with disabilities] are prioritized in terms of jobs, and for many things. It’s not a lie, and I’ve lived it, that people in our rural zones lived in straw houses with mud roofs…and now there are real houses in our rural zones, and not just in our rural zones, but in the urban zones, the million and some houses that have been constructed are a reality.… There’s still much to do, but this is a reality…. And it’s not a lie that in any street corner you go to, people will talk to you about politics, about what’s happening, about the international situation, if they participated or not, if the communal council stole the money or didn’t steal the money. There’s a political participation that can’t be hidden.”

GLIMMERS OF HOPE

Like rice, shampoo, black beans, and many other products, it is not easy to find hope in Venezuela these days. Yet there are sparks throughout the country. Confronted with the increasing challenges of obtaining food, many Venezuelans are taking matters into their own hands, and backyards. When I arrived at her house in Carora, Myriam Gimenez asked, “Has Victor [her husband] shown you the garden?” When I said no, she led me to her backyard and proudly showed me various crops, including black beans, peppermint, and medicinal oregano, which she and Victor planted since my last visit in December. Pointing to cornstalks in her next-door neighbor’s yard, Gimenez said, “Everyone on the block is planting now.” Gimenez also says that bartering has become increasingly common as a way for people to get what they need.

Myriam Gimenez in her backyard garden in Carora.(Gabriel Hetland)

Atenea Jimenez is involved with “a network of communal production and consumption” of food and basic goods. Sub-networks link 100 communes in states throughout the country, including Yaracuy, Trujillo, Mérida, Lara, and multiple states in the greater Caracas area. Jimenez belongs to a network connecting seven communes, comprising 2,100 families. “We have our own trucks and we bring fresh produce to the city. We sell everything at low prices to consumers. For instance, we sell tomatoes for 400 bolivares/kg, a third the price elsewhere. And we bring certain products that we produce in the city, such as shampoo and disinfectant, to the countrywide, where they’re hard to find.” Jimenez says, “There’s a permanent distribution of food. It’s all planned. We use a community census to distribute foods that people ask for.” The system is not perfect. “We’ve lost some food” due to inaccurate estimates of how much demand there would be in certain areas, says Jimenez. She adds, “There’s minimal corruption because it’s all done collectively. We write everything down, and then report what’s being done.”

In addition to grassroots efforts to build a new, communal system of production and distribution of food and basic goods, there are also grassroots efforts to “rescue Chávez’s legacy” and forge an alternative way of doing politics that stands in contrast to the corruption and bureaucracy of the government. This movement, referred to by some as “critical Chavismo,” has taken on several expressions. According to Jimenez, there are two networks of critical Chavismo, made up of leftist parties and social-movement organizations that support the government in a critical way, and are careful to maintain their autonomy. One network, known as the Frente Patriótico Hugo Chávez (Hugo Chávez Patriotic Front), brings together “the PPT [Fatherland for All, a left party], the Corriente Revolucionaria Bolívar y Zamora, a radical current within the PSUV, and a number of smaller movements.” The Red de Comuneros is part of a second network, “which doesn’t have a name yet, and includes the PCV [Communist Party], workers movements, some unions, including Polar, a fraction of the CANTV union, and the Alexis Vive collective [a grassroots movement based in 23 de Enero parish in Caracas and active in other states, including Lara].” Jimenez says, “Our slogan is: Neither Bureaucracy, nor a Pact with the Bourgeoisie.” This movement is trying to push the government “to really go with the people, and not just say that they are.”

There are grassroots efforts to “rescue Chávez’s legacy” and forge an alternative way of doing politics.

The most high-profile recent action of the “critical Chavismo” movement—which Jimenez tells me “is very diverse” and represents many distinct lines of thought—was a march against bureaucracy and corruption in April in Caracas, which attracted 1,500 people. Johnny Murphy, who is active with the Alexis Vive collective in Carora and Barquisimeto, attended the march and says the organizers were pleased by the turnout. “We only expected 1,000,” he said. I asked Atenea Jimenez if the march elicited a response from the government. She said, “The response of the government was total silence, as though it hadn’t happened. No one called us afterward.” This is in contrast to the government’s aggressive actions against Marea Socialista, a Trotskyist formation that split with the PSUV in the December 2015 elections and unsuccessfully sought to run its own candidates in the election, but was blocked by the National Electoral Council. Marea Socialista has been fiercely criticized by the government, which recently raided the group’s headquarters. Jimenez says that while she has not worked closely with the group, “I don’t view Marea Socialista as the enemy. They’re part of critical Chavismo.”

Grassroots struggles are necessary but will not be enough to end Venezuela’s deep crisis. Economic policy changes are sorely needed. In the long term, Venezuela must make a serious effort to address its chronic dependence on oil, which makes the country so vulnerable to fluctuations in the global economy. In the short term, the government must address the currency crisis. In contrast to The New York Times’s recent assertion that “the Maduro regime has been unwilling to even contemplate” needed economic reforms, the government has been engaged in recent discussionswith a team of economists from UNASUR, the Union of South American Nations, about a macroeconomic plan to help stabilize the economy and trigger economic growth while protecting vulnerable low-income sectors,” according to an adviser involved in the talks. The core of the plan would be a free float of the bolivar, which would eliminate the current system of three separate currency exchange rates, the two official rates and the parallel rate. Advocates of the plan believe that this will provide greater economic stability and, crucially, eliminate one of the main sources of corruption, the syphoning off of preferential dollars by corrupt businesses, often in cahoots with state officials. The UNASUR plan also calls for creating a universal “socialist card” that would allow citizens to buy goods, the prices of which would no longer be directly regulated, at reduced rates. The hope is that this would protect the poor while minimizing opportunities for corruption. Maduro has not yet agreed to this plan, but those with inside knowledge say they are “cautiously optimistic” about the government’s commitment. Whether it will be enough to get Venezuela out of its severe crisis is an open question.

To have any shot of doing so, the government will need to calm citizens’ nerves, and assure them that it has the ability to provide for their needs. The current domestic and international climate of fear-mongering, with escalating calls for foreign intervention and exaggerated predictions of Venezuela’s imminent demise, is far from propitious. Instead of encouraging imperial interventions that will only make change more difficult, the international community, including foreign journalists, should be working hard to provide accurate information about the dire, but not apocalyptic, situation confronting Venezuela.

GABRIEL HETLAND is assistant professor of Latin American, Caribbean, and US Latino Studies at University at Albany, SUNY. His writings on Venezuelan politics, participatory democracy, capitalism, labor, and social movements have appeared in Qualitative Sociology, Work, Employment and Society, Latin American Perspectives, Jacobin, The Nation, NACLA, and elsewhere.