Hafez al-Ayoubi

OCT 23, 2025

An influx of Israeli settlers and investors into Cyprus has raised alarms among Cypriots and regional observers who see echoes of Haifa’s past in Larnaca’s present. Beneath the real estate surge lies a deeper Israeli project to reshape the Eastern Mediterranean order – one in which Cyprus is both gateway and outpost.

Last year, reports multiplied of Israelis purchasing land and property across the Republic of Cyprus, an EU member. Though the numbers remain modest, the pace of acquisitions has quickened. Some interpret this wave as a symptom of Israel’s fading self-image as “the safest place for Jews.”

Others see it as a byproduct of the shifting geopolitical architecture of the Eastern Mediterranean, in which Cyprus occupies a critical node of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s expanding maritime vision.

The new frontier

Cyprus, the Mediterranean’s third-largest island, has been divided since Turkiye’s 1974 invasion of the north, which established the unrecognized Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC). About 400,000 Turkish Cypriots inhabit that section under Ankara’s patronage, while the internationally recognized southern Greek Cypriot Republic – home to 1.3 million people – now finds its coastline increasingly dotted with Israeli-owned real estate.

Statistics alone obscure the larger pattern. According to the Cyprus Audit Authority, non-European buyers over the past five years have come primarily from Lebanon (16 percent), China (16 percent), Russia (14 percent), and Israel (10 percent).

Meanwhile, the Jewish community in Cyprus, around 4,000 families – roughly 15,000 people – has expanded from just a few hundred two decades ago. In 2003, there were between 300 and 400 people, rising to around 3,500 in 2018, a modest but symbolically potent growth spurred by three crises: COVID-19, Israel’s judicial reform turmoil, and the war on Gaza.

Yet, this migration wave reflects a broader reversal: a rising number of Israelis leaving the country. The Knesset Research and Information Center reported that some 145,900 people emigrated between 2020 and 2024 – a trend Yedioth Ahronoth linked to the aftermath of 7 October, warning of “strategic risks.”

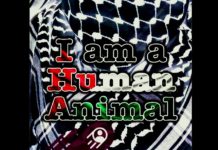

Theodosis Pipis, a researcher at the Center for International Strategic Studies and Analyses (KEDISA) in Athens, likens the reality of Larnaca today to the city of Haifa in the 1920s in an article titled ‘Israeli Expansion into EU via Cyprus.’ He says that “heavy investment in coastal cities such as Haifa led to the economic control of Palestine.” Pipis explains that Haifa was a sparsely populated port city similar to today’s Larnaca, but after the declaration of the State of Israel and the expulsion of Palestinians from their homes, Jewish settlers became the majority in Haifa:

“Historically, the case [of] Haifa could deed as a foreshadowing of what could happen to Cyprus should the economic investment ensue. A port city (akin to Larnaca), with low population density. By the time the Jewish settlers expelled Palestinians from their homes and proclaimed Palestine as the State of Israel, Jewish settlers had become the majority population in Haifa.”

Israel’s “backyard in Cyprus”

Beyond statistics lies a more troubling pattern. The formation of exclusive Israeli enclaves, particularly around Larnaca. Reports observe that “Locals are priced out. Infrastructure – synagogues, kosher supermarkets, private schools” are being built quickly, “The same settler-colonial template used in the West Bank now appears to be taking root in places like Pyla and Limassol.”

What is of particular concern is that “Many of these settlers are not disillusioned liberals but deeply Zionist and well-resourced.”

In June, spokesperson for the Progressive Party of Working People (AKEL), Stefanos Stefanou, said, “They are building Zionist schools, synagogues, gated enclaves … Israel is preparing a backyard in Cyprus, and this cannot but sound the alarm for us.”

The Hasidic Chabad movement, known locally as Chabad, established Cyprus’s first official Jewish worship site in 2005 near Larnaca – the island’s first in centuries. Today, it operates six synagogues – under the guidance of Chief Rabbi Ze’ev Raskin.

Historically, Cyprus figured in early Zionist colonization schemes. A US State Department report, ‘The Justice for Uncompensated Survivors Today (JUST) Act Report: Cyprus,’ records that “There were approximately 100 Jews in Cyprus in the early 20th century. After the rise of Nazism in 1933, hundreds of European Jews escaped to Cyprus, which was a British colony at the time.”

The father of modern Zionism, Theodor Herzl, himself once promoted the “Cyprus option” as leverage in negotiations for Palestine. During the Third Zionist Congress in 1899, delegate David Tricht argued that “Cyprus is the most suitable location – unattractive to Europeans, yet close to the Land of Israel.”

Invitations were issued especially during the Third Zionist Congress in 1899. Tricht said:

“Jews shouldn’t seek refuge in lands favorable for European settlement, as they would encounter resistance in every such country. They also won’t be able to efficiently settle in tropical regions. Given these conditions, Cyprus is the most suitable location for Jewish settlement. While the island isn’t a magnet for European settlers, its climate is suitable for Europeans, and notably, it is in close proximity to Israel, serving as a gateway to it.”

About two months later, Herzl wrote:

“Given that the Ottoman government shows no inclination to reach an agreement with us, some want to turn to this island, which is under British control and which we could enter at any time. Until the next congress, I still have control over the situation. But if no results are in hand by then, our plans will sink, like water on the island of Cyprus.”

In 1902, Herzl submitted written evidence to the British Parliamentary Committee on Alien Immigration and circulated a pamphlet outlining how Jewish migration to England and the US could be eased by promoting colonization projects, including one in Cyprus.

In the same year, he also discussed settlement proposals with British Colonial Secretary Joseph Chamberlain, mentioning the island as a possible location for Jewish colonization, and that “The Muslims will move away, the Greeks will gladly sell their land at a good price and migrate to Athens or Crete.”

A safe haven or strategic outpost?

The “historic Jewish presence” in Cyprus remained marginal until the early 21st century, but recent events have catalyzed a dramatic shift. The June war with Iran and escalating regional tensions last summer accelerated Israeli purchases, particularly in coastal cities.

At the height of the conflict, a Cypriot real estate platform reported that “Israelis have been actively contacting their brokers, expressing concern and impatience about the resumption of air service. Many of them say outright: ‘We want to go home,’ meaning Cyprus.”

The platform added that “Many Israeli citizens view Cyprus as a safe and stable alternative, convenient for both temporary residence and long-term investment. For many of them, Cyprus has become a ‘second home.’”

Israeli experts, meanwhile, say additionally, “some Israelis are looking for the option to spread their finances and risks.”

Nevertheless, Cypriot politicians warn of opaque ownership networks. Loopholes allow companies to evade restrictions limiting non-EU nationals to two properties.

Takis Hadjigeorgiou, a former member of the European Parliament’s foreign affairs committee, recounts that a year ago, the issue of ownership of non-Europeans, especially Israelis, was raised before the “top state official responsible for land and property issues in Cyprus.”

“Yes, I’ve heard that too,” the official said, adding, “But didn’t we used to say it was the Lebanese buying us out?”

The Greek Herald has since echoed fears of “demographic engineering” and warned that if such “changes continue unchecked, they may lead to the irreversible loss of its ancient Hellenic identity.”

“A wave of companies and individuals of Jewish/Israeli origin are systematically purchasing properties throughout EU-Cyprus – including the Turkish-occupied north – raising public concerns about the implications of such a practice.”

Whatever the motives of Israeli migrants, they are entering a land marked by trauma and fierce nationalism. Cypriots, though welcoming tourists, remain haunted by their own partition. Many sympathize with Gaza and resent the use of British military bases for Israel’s wars. Beneath polite coexistence, suspicion simmers.

The Mediterranean Arc

Chief Rabbi Raskin, head of the Rabbinical Court of Cyprus since 2003, has described Cyprus as Israel’s “backdoor.” According to Yonatan Brander of the Oslo Peace Research Institute (PRIO), who authored the 2022 paper ‘A Strategic Friendship: Israeli Perceptions of the Israel–Cyprus Relationships,’ Israeli policymakers view ties with Nicosia as “the cornerstone of a regional order that it is interested in shaping and preserving.”

Two trajectories now define Israeli policy on the island. First, Netanyahu envisions Cyprus as part of a new geopolitical bloc binding Israel to Europe and the Mediterranean energy network. Nicosia’s willingness to host reconstruction discussions for Gaza underscores its emerging diplomatic role. Cyprus provides geographic depth, an air–sea corridor, and an EU voice friendly to Tel Aviv’s ambitions.

Second, Israel’s deepening economic and institutional entrenchment risks transforming Cyprus into a subordinate dependency rather than an equal partner. Ankara has already grown wary, viewing this entente as a second Israeli frontier along its periphery, complementing its indirect border in Syria.

A study by Tel Aviv University’s Moshe Dayan Center on the 12-Day Israel–Iran war’s impact on the alliance between Israel, Greece, and Cyprus, namely the “Mediterranean Arc” – a strategic corridor connecting the Atlantic to the Indian Ocean through the Mediterranean, Red Sea, and Arabian Sea. The alliance, it says, “anchors Israel’s new maritime sphere of influence and deepens the rift with Turkey.”

Since the 2010s, cooperation between Israel and Cyprus has become a geopolitical constant. Nicosia’s participation in EastMed gas exploration, bolstered by support from Washington, Riyadh, and Abu Dhabi, has aligned it against Ankara. Reports last year indicated that Israel delivered three shipments of Barak MX air defense systems to Cyprus – a development that Turkish media warned could destabilize the region.

Concerns deepened after the Cyprus Mail reported that “The government’s failure to deny reports about the presence of Israeli security personnel at the perimeter of the Larnaca Airport fence and in the air traffic control-tower … suggested the reports were correct and that the Republic had surrendered the security of its main airport to the security forces of another state.”

Intelligence, bases, and warnings

Multiple regional sources claim that Israel now relies on Cyprus for intelligence and operational logistics in the Levant. Cooperation reportedly includes the transfer of surveillance technology, the export of spyware through Cypriot fronts, and the establishment of “joint intelligence channels for targeting Iran and the Axis of Resistance,” according to Iranian academics. These networks, they argue, enable Israel to “use Cyprus as a staging ground for simulating potential future conflicts with Hezbollah and Iran, disrupting the Axis of Resistance’s logistical routes, and targeting Iranian vessels near the island.”

This is exactly what the late secretary-general Hassan Nasrallah warned last June, addressing the Cypriot government. He said that “Opening Cypriot airports and bases to the Israeli enemy to target Lebanon would mean that the Cypriot government is part of the war, and the resistance will deal with it as part of the war.”

Two months later, one former senior Israeli ambassador to Cyprus told the Media Line that these warm relations “[have] not come at the expense of our other friends in the region,” adding that “We believe Israel should be integrated into the region, and Cyprus can play a bridging role in this because we have equally good relations with everybody. In our mind, developing this relationship with Israel does not mean we have to sacrifice other relationships.”

Netanyahu has personally cultivated this transformation. During his September 2023 visit to Nicosia, he declared that the two nations “have a wonderful friendship,” claiming that “western civilization is the result of basically Greek culture and Judaism fused together.” Barely a month later, Israel’s devastating war on Gaza commenced following Operation Al-Aqsa Flood.

The new Haifa

The island hosted Netanyahu’s “historic” 2012 visit – the first of its kind – following reciprocal presidential exchanges in 2011.

At the time, Haaretz noted that Cypriot observers “say the key to the improving relations lies in those common interests – among them, what is referred to as “the division of the sea and its treasures” between the two countries (Lebanon is a hidden partner in this ) – and in the belief that Israel’s good relations with Washington will magically rub off on the island.

Today, a parallel development unfolds in Lebanon, where the Council of Ministers is discussing a maritime border deal with Cyprus, amid warnings it could cost Lebanon around 5,000 square kilometers of maritime rights, reflecting US pressure to align East Mediterranean gas interests with Israeli priorities.

The question now, for Cypriots and the wider region, is whether these shared interests bring prosperity or peril. As new settlers plant their flags and ideology on an island long scarred by division, Cyprus risks becoming another Haifa.

.

We remind our readers that publication of articles on our site does not mean that we agree with what is written. Our policy is to publish anything which we consider of interest, so as to assist our readers in forming their opinions. Sometimes we even publish articles with which we totally disagree, since we believe it is important for our readers to be informed on as wide a spectrum of views as possible