By David Lorimer

May 24, 2018

Review of David Ray Griffin, Bush and Cheney: How They Ruined America and the World (Olive Branch Press, 2017, 398 pp.)

published in Paradigm Explorer: The Scientific & Medical Network (London, 2018/2)

This brilliant, meticulous and searing analysis is David Ray Griffin’s most powerful and important book about the hegemonic foreign policy ambitions of US neoconservatives and the way in which 9/11 was used to pursue these Machiavellian ends. This is a book that should have been written by a mainstream investigative journalist, but David has done their work for them, which they have signally failed to do by accepting the 9/11 Commission claims and labelling those who questioned these as ‘conspiracy theorists’, a term originally devised by the CIA to use against their opponents when the position of plausible deniability in undercover operations was under threat. The book is widely endorsed, for instance by Professor Daniel Sheehan, who remarks that it is ‘a clear and non-sensationalist presentation of the historical and scientific facts, by one of our generation’s most cogent thinkers. This book should convince any honest and objective person – with a political and scientific IQ above room temperature – that we have been systematically lied to about the events of 9/11 and the American invasions in the Middle East.’ Seasoned readers of this journal will recall that I have reviewed all of David’s books on 9/11 – here he summarises his case in the context of the foreign-policy background, with the first part devoted to this, and the second to a concise discussion of the shortcomings of official explanations of 9/11.

The failure to prevent 9/11 attack was in itself a massive intelligence disaster, and may partly be explained by some of the background elaborated in this book. The aftermath of 1989 and the fall of the Soviet Union left the US in a unipolar geopolitical position and without any clear enemy. The war on terror declared in the wake of 9/11 gave rise a new enemy and justified further increases in military expenditure on ‘security’ grounds. During the 1990s, neoconservative thinkers had urged the US to consolidate its status as an unchallenged superpower and, where deemed necessary in terms of its strategic interests, to act unilaterally to establish a Pax Americana. This injunction was reinforced by the doctrine of American exceptionalism, only recently reiterated by the incoming Secretary of State, Mike Pompeo, and also espoused by John Bolton, the newly appointed National Security Adviser. As a ‘benign’ power, the US has the right to intervene where it sees fit; other countries such as Russia may be equally unique, but they are not ‘exceptional’.

In 1997, William Kristol founded the Project for the New American Century (PNAC) with a call to shape this new century in a way favourable to American principles and interests. In September 2000, PNAC published a document called Rebuilding America’s Defences where they advocated the use of US military supremacy to establish an empire including the whole world – hence ‘the next president of the United States must increase military spending to preserve American geopolitical leadership.’ This aim should be understood in the Pentagon context of achieving Full Spectrum Dominance, a policy already developed in the 1990s. Chillingly, the document reflected that the process of transformation might be a slow one in the absence of ‘some catastrophic and catalysing event – like a new Pearl Harbour’ – 9/11 was this event and enabled a fast track of neoconservative policies, beginning with the attack on Afghanistan that had actually been planned many months previously, and the destructive consequences of which are spelt out in detail. It should be noted that Dick Cheney has been a leading figure in the neoconservative movement, and it would be more accurate to describe the Bush – Cheney administration as the Cheney – Bush administration, at least in the first term.

The chapter on military spending, pre-emptive war and regime change is an eye-opener. The idea of pre-emptive-preventive war came to be known as the Bush Doctrine, elaborated in a 2002 national security strategy document with the dangerous clause that America can in self-defence ‘act against such emerging threats before they are fully formed’ – I will come back to this below when discussing drones. Challenging regimes hostile to US interests meant overthrowing them and replacing them, and the 2002 list ominously included Iraq, Iran, Syria, Lebanon, Libya, Somalia and Sudan. The events of the last 15 years show how dangerous it is in terms of unintended consequences to sow a wind without reaping a whirlwind: the emergence of ISIS as a result of the invasion of Iraq is just one example.

This document was written by Philip Zelikow, who would later be named the executive director of the 9/11 commission.

The next chapter is a detailed analysis of the Iraq war and the propaganda campaign of lies required to justify it, both in the US and the UK. David refers to meetings by Sir Richard Dearlove, head of MI6, with members of the Bush administration and CIA director George Tenet. Dearlove remarked that ‘the intelligence and facts are being fixed around the policy’, which was also the case in the UK with the so-called dodgy dossier. Amazingly, a 2008 report by the Centre for Public Integrity enumerates as many as 935 false statements made by members of the Bush administration in the two years following 9/11. David itemises a few of these with reference to weapons of mass destruction as well as biological and chemical weapons. During this time, the Joint Chiefs of Staff produced a much more cautious assessment, which was set aside. In addition, (p. 61) CIA analysts felt pressured by Dick Cheney to make their assessments fit with the Bush administration’s policy objectives, which dictated the conclusions their analyses should yield. The consequences of the Iraq war are well-known and include an estimated 2.3 million Iraqi deaths, 4,500 American deaths and hundreds of thousands of serious injuries, including 320,000 brain injuries. As to the economic cost, this had reached $4 trillion by 2014, a devastating opportunity cost in terms of what the money might have been spent on. It should also be noted that the contract for rebuilding Iraqi infrastructure went to Halliburton, of which Dick Cheney is a major shareholder and former chief executive officer.

Space does not permit a detailed discussion of all the global chaos brought about by US interventions in the Middle East on the basis that it could solve all of its problems by means of military power. Chaotic collapse was regarded as a form of ‘creative destruction’ providing a basis for destabilising a regime and eventually removing the incumbent, especially in this geopolitically significant area for oil and gas (p. 109). David discusses Libya, showing how the same kinds of lies were used to bring about regime change there, then he moves on to Syria, where the intractable disaster is ongoing, as we all know. In addition to military factors, it may also be a case that a form of weather warfare was used (this is not suggested in the book) to help create the drought as a key destabilising factor; in either event, whether deliberate or due to climate change, the drought was significant. In Syria, out of the pre-war population of 22 million, 11% have been killed or injured, 5 million have fled the country and a further 8 million are internally displaced. In addition, as we know, this chaos also led to the refugee crisis that precipitated the Brexit vote.

David devotes a separate chapter to drone warfare, posing and responding to a number of key questions: are drone killings acceptable? Are they de facto assassination? Do drone strikes rarely kill civilians? Are drone strikes used only when capture is impossible? Are drone strikes used only for imminent threats? Do drone strikes help defeat terrorism? Don’t drones at least keep American warriors safe? There is no good case to be made for drone warfare extrajudicial killing in the name of ‘self-defence’; sometimes ‘signature strikes’ were employed and continued on a large scale during the Obama administration. The justification is tortuous to say the least where ‘an imminent threat of violent attack does not require the US to have clear evidence that a specific attack on US persons will take place in the immediate future’ (p. 146). This is a ‘more flexible’ understanding of imminence which ‘defines the term in a way that excludes its only actual meaning’ (!).

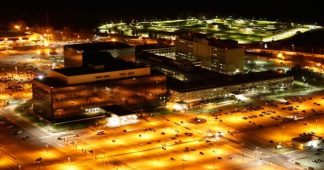

The chapter on shredding the Constitution makes depressing reading where ‘unaccountable executive power has replaced due process and the checks and balances established by the US constitution’, first embodied in the Patriot Act. David systematically shows how various amendments to the Constitution have been violated: the first on freedom of speech and assembly, the fourth on security against unreasonable searches and seizures, and the fifth relating to deprivation of life, liberty or property without due process of law. In addition, torture violates the Constitution, and the overall result has been an undoing of democracy in the name of security – an Orwellian outcome.

After chapters on potential nuclear and ecological holocaust (the latter the subject of one of David’s previous books – Unprecedented), he moves on to a summary analysis of the events of 9/11 and its aftermath. Here he condenses the findings of his previous books to show how numerous miracles, defined as violations of the laws of nature, were necessary in order to sustain the 9/11 Commission’s official explanation. He shows how the choice of Philip Zelikow as Executive Director of this supposedly impartial and independent commission was in fact an insider selection leading to a foregone structure and conclusion and tight control on individual commissioners. As early as March 2003, prior to the first meeting of the commission, Zelikow had prepared a detailed outline including chapter headings, subheadings and sub sub-headings. The pre-ordained task was to explain how the building had been brought down by fire and the impact of the airliners.

So far as the Twin Towers are concerned, their core consisted of 287 steel columns, and steel does not begin to melt until 2,770°F, while fires caused by kerosene can only rise to around 1,700°F. The Twin Towers collapsed at virtually free fall speed, as did WTC 7, which was not hit by an aeroplane, a fact that was not even mentioned by the 9/11 Commission.

The official reports on WTC 7 and the Twin Towers were provided by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), which was an agency of the Bush-Cheney administration. Its reports are more political than scientific as it is a fact of physics that a steel frame building can only come down essentially in freefall if all the core columns are severed simultaneously by explosives – in the case of Building 7, the roofline remained virtually horizontal throughout the sudden collapse. Readers can consult comparative videos for themselves showing an example of controlled demolition compared with the destruction of Building 7. In addition, massive sections of steel columns and beams were horizontally ejected from the Twin Towers up to 650 feet, which is quite inconsistent with the vertical effects of gravitational collapse. David summarises six miracles required by the official explanation that, in the view of a former NIST employee, ‘reached a predetermined conclusion by ignoring, dismissing and denying the evidence.’ In other words, the official account – and all the more so in the case of Building 7 with 82 steel columns – is a lie.

In his conclusion and after further short chapters on the Pentagon attack and Mohamed Atta, David lists 15 miracles required by the official 9/11 commission explanation. He asks why mainstream media have not properly examined the evidence, and one significant factor already mentioned is the fear of being labelled a ‘conspiracy theorist’, implying credulity, gullibility and irrationality. In the case of David Ray Griffin, nothing could be further from the truth: his analysis is thorough and forensic. He explains how the CIA invented this conspiracy theory tactic in 1964 in the wake of the Warren Report into the Kennedy assassination. It has become a powerful and intimidating rhetorical device, especially for journalists who pride themselves on their scepticism and objectivity.

Rather than follow the a priori argument that no government could be evil or competent enough to cover up 9/11, David urges people to look at the empirical evidence – and if you, the reader, are feeling similarly uncomfortable, I encourage you to read this book and his other ones for yourself and to understand the logic of false flag operations that can be attributed to opponents by means of a suitable propaganda campaign. So far as 9/11 is concerned, there is a large body of informed and expert professional opinion across various disciplines that has studied the evidence and concluded that the official account is false – see also the 9/11 Consensus Panel, the results of which was soon be published in 9/11 Unmasked: A Six-Year Investigation by an International Review Panel. This book is a highly significant contribution to exposing the Big Lie of 9/11 and the neoconservative foreign policy background, and is as such a passionate plea for mainstream media exposure to put a stop to further Machiavellian ambitions for full spectrum dominance of the world.