By Benjamin Santer*

Nov 28, 2025

November 29 is an important day in the history of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. It’s also an important day in the history of climate science.

You’ve probably heard of the IPCC. It was founded in 1988 by the United Nations Environment Programme and the World Meteorological Organization to inform governments, policymakers, and the public about human-caused climate change. The IPCC’s main job is to assess the state of climate science every six to seven years. The thousands of climate scientists who contribute to IPCC assessments provide sound scientific information on which rational climate policies should be based. This information is critically important in the current bewildering moment, when influence peddlers and conspiracy theorists can spread alternative facts and disinformation around the world with the click of a button. With over 190 member countries, the IPCC is not the voice of just a handful of countries, but an authoritative representative for the global scientific community.

The IPCC’s assessment reports are written by scientists, mostly working pro bono. Assessments rely on subject matter experts from academia, research labs, and industry representatives. Writing an IPCC report is not something that’s done to get rich quick, achieve fame, or alter world systems of government. Participating in an IPCC assessment is an unpaid, multi-year commitment by individuals with precious and finite stores of time and energy.

In 2007, the IPCC shared the Nobel Peace Prize with Al Gore. Both were recognized “for their efforts to build up and disseminate greater knowledge about man-made climate change, and to lay the foundations for the measures that are needed to counteract such change.” I nearly drove off the road on my way to work when I heard the news on my car radio.

A mix of emotions welled up. Surprise. Elation. And relief. With the announcement that the IPCC had “created an ever-broader informed consensus about the connection between human activities and global warming,” an unseen weight was lifted. By 2007, I had already spent years of my life contributing to—and defending—the “consensus about the connection between human activities and global warming.” Now that consensus had been acknowledged by the Nobel Prize Committee.

My involvement with the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change started in 1990. I served as a contributing author to one chapter of the IPCC’s first assessment report: “Detection of Climate Change, and Attribution of Causes,” or “D&A” in climate scientist lingo. The task of the two lead authors and 35 contributing authors of the D&A chapter was to evaluate evidence from studies that had searched for human effects on Earth’s climate. What had these investigations found?

In 1990, we concluded that “The unequivocal detection of the enhanced greenhouse effect from observations is not likely for a decade or more.” Put differently, the jury was out on human culpability for climate change. In 1990, it was still too early to tell whether burning fossil fuels had significantly altered Earth’s climate.

But a mere five years later, in the IPCC’s 1995 Second Assessment Report, the scientific jury reached a very different verdict.

Over three days in November 1995, climate scientists and IPCC government delegates convened in the Palacio de Congresos in Madrid, Spain, a building adorned with a stunning Miró-inspired mosaic at the entrance—a poignant reminder that humans can create things of great beauty in the world.

The task of the scientists and delegates in Madrid was to approve the draft of the Summary for Policymakers (SPM) of the IPCC’s Second Assessment Report, and to accept the 11 underlying report chapters on which the SPM was based.

Late in the evening of November 29, after three days of tense and difficult discussions, all 177 government delegates present in Madrid—representing the interests of 96 countries—approved a historic 12-word finding. Their conclusion? “The balance of evidence suggests a discernible human influence on global climate.” While a small number of individual studies had previously reached similar conclusions, the claim of a “discernible human influence” on climate was a first for the international scientific community. A human-caused climate change signal had been identified. We could see the signal. It was there in data. Humans were no longer innocent bystanders in Earth’s climate system.

Those 12 words from Madrid are inextricably intertwined with my life, like the two strands of nucleotides that form the double helix structure of DNA. I was the convening lead author of the D&A chapter—chapter 8—in the 1995 IPCC report. It was our chapter that reached the “discernible human influence” conclusion.

I’ve been explaining how and why we reached that conclusion for the last three decades.

Today, in November 2025, it is important to commemorate the 30th anniversary of the Madrid IPCC meeting. It’s important to look back at what happened during those three days in the Palacio de Congresos; to make sense of that moment in time; to see Madrid as part of a trajectory—a bending of the arc of history towards ever-greater scientific understanding of the human effects on climate. And it’s important to reflect on what the late Stanford climatologist Steve Schneider referred to as the nightmare aftermath of Madrid. What happened in Madrid did not stay in Madrid. It changed the world.

Madrid was a confluence of powerful forces. There were the Saudis and Kuwaitis, with vested economic interests in the continued exploitation of fossil fuels. There were non-governmental actors with similar vested interests, organizations like the Global Climate Coalition, a misleadingly-named lobbying organization representing “the interests of the major producers and users of fossil fuels.” There were governments concerned about the impact of rising sea level on the very survival of their countries. There were the IPCC leaders, seeking to ensure that the 1995 report was an accurate reflection of the state of the science, and that all countries present in the Palacio de Congresos had their voices heard and respected. And there were the scientists, seeking to ensure that climate science was fairly represented in the 1995 report—that politics did not trump science; that the tail did not wag the dog.

The Madrid meeting was an extraordinary event. The conflict between science and forces antithetical to science, what I call “forces of unreason,” played out openly on a world stage. The forces of unreason did not want to improve the clarity of the science in the 1995 IPCC report. They did not want to understand the evidence for human fingerprints on climate. They wanted to destroy the credibility of the evidence. The forces of unreason wanted to hold the party line of the fossil fuel industry. The party line stipulated that the science was too uncertain. The party line held that computer models of the climate system were unreliable. The party line claimed that the main characters in the unfolding play of climate change were non-human actors like the Sun, volcanoes, and large natural oscillations in Earth’s atmosphere and oceans.

The Madrid meeting involved a steep personal learning curve. It was my first meeting with IPCC government delegates. I soon realized that not everyone in the Palacios de Congresos shared the same aspirational goal of accurately assessing the state of climate science. And I soon realized the critical importance of language. Language could be used to distill the essence of complex science into 12 words. It could also be used to cloud and obscure rather than to distill: to sow doubt in the minds of the jury.

Let me give you a little smörgåsbord of the criticisms that chapter 8 received during and after the Madrid IPCC meeting. I was told that there was “no scientific basis for chapter 8” and that it should be removed from the 1995 IPCC report. I was told that scientific uncertainty precludes us from making assessments of the credibility of D&A studies, and that our use of words like “preliminary”—as in “preliminary evidence”—meant that evidence from new studies shouldn’t be discussed. After all, if findings are “preliminary,” they could be overturned tomorrow. I was told that chapter 8 was solely based on the opinions of one or two scientists. And I was told that if scientists had not yet (back in 1995) reliably quantified the size of human influences on climate, those influences must be trivially small.

The scientists in the room did not remain silent in the face of such specious criticism. We responded. We explained in any field of science, there are things known with high confidence and things that are uncertain. Uncertainty in one component of the science does not mean that everything is uncertain. We noted that there is, and always will be, some irreducible uncertainty in our quantitative understanding of natural and human influences on climate. Such uncertainty is not ignored. It is an integral part of climate science.

November 29, 1995, was the final day of the Madrid meeting. Hours of the plenary discussion focused on the 12-word distillation of the D&A findings in the summary for policymakers. In the October draft report sent to all Madrid participants before the meeting, the bottom-line finding of chapter 8 was this: “Taken together, these results point towards a human influence on climate.” After exhaustive consideration of all the D&A evidence in Madrid, the final text was not fundamentally different: “The balance of evidence suggests a discernible human influence on global climate.”

The differences between the two statements came down to a few key words: “the balance of evidence,” “suggests,” and “discernible.”

Each of these was its own battlefield. Should “balance of evidence” be “weight of evidence” or “preponderance of evidence,” all of which could have different implications if IPCC findings were used to assess liability for climate change in a court of law? Was the verb “suggests” too weak? Should “suggests” be replaced by “indicates” or “demonstrates”? And what was the most appropriate qualifier for the human influence on climate? Was it “measurable” or “detectable”? “Appreciable,” “significant,” or “identifiable”? How would each of these proposed words translate into different languages?

Part of the difficulty in Madrid was in figuring out how to synthesize the findings from dozens of different D&A studies. Each study used different models, data, and statistical methods, and couched its D&A findings in different ways. What was the best way to compare this collection of disparate individual studies? Could we come up with an accurate, scientifically-defensible statement about the overall likelihood that a human-caused climate signal had been identified?

In the end, I believe that the cautious 12-word exit statement from Madrid accurately captured the scientific understanding available in 1995. Some Madrid participants felt that the science warranted a stronger conclusion. Some felt that the science warranted a weaker conclusion. But as a delegate from the Netherlands noted in the plenary session in the wee hours on the last day of discussions: “I would like to point out that we are not here to make strong or weak statements, but we should try to reflect the state of the science. And I believe the authors (of chapter 8) have been successful in doing this.”

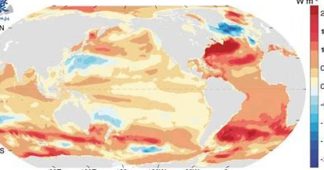

Thirty years after Madrid, the “discernible human influence” finding seems unexceptional. The science of climate change detection and attribution moved on. It strengthened. Every IPCC assessment after 1995 upped the level of confidence in the identification of human-caused climate change signals (see Fig. 1). In 2021, in the IPCC’s sixth and most recent assessment report, the D&A chapter concluded that: “It is unequivocal that human influence has warmed the atmosphere, ocean, and land.”

Some are skeptical of the IPCC and of anything associated with “internationalism” or the United Nations. But findings of human fingerprints on climate are not unique to the IPCC. For example, a home-grown 2025 review of climate science conducted by the U.S. National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine affirmed the IPCC’s D&A findings, noting that: “Improved observations confirm unequivocally that greenhouse gas emissions are warming Earth’s surface and changing Earth’s climate.”

Many factors contributed to the increased scientific confidence in anthropogenic signal identification in the 30 years from 1995 to 2025. There were improved climate models—and more of them. There were improved and longer observational climate records. There was better understanding of the human and natural factors that affect Earth’s climate. Climate model results became available for community-wide analysis, leading to more comprehensive model evaluation, and ultimately, to even better models. Model evaluation was also made easier through the development of infrastructure for efficient sharing of large datasets across the scientific community. Model Intercomparison Projects (MIPs) allowed scientists to explore whether anthropogenic signal detection was robust to uncertainties in current climate models, and to put error bars on projections of future climate change.

Progress was also enabled by the development of statistical ‘fingerprint’ methods for disentangling human and natural influences on climate. These methods were not in widespread usage in 1995. After Madrid, fingerprint methods were applied not only to traditional staples of D&A studies, like surface and atmospheric temperature, but also to rainfall, clouds, humidity, salinity, ocean heat content, atmospheric circulation patterns, Arctic sea ice extent, and dozens of other independently monitored variables. Fingerprinting revealed that anthropogenic climate signals were not only “unequivocal,” they were also ubiquitous. Human fingerprints were all over Earth’s climate system.

But in its time, the 1995 Madrid IPCC meeting resulted in an extraordinary claim—that a human-caused climate change signal had been identified. That claim was subjected to extraordinary scrutiny. The tires were kicked. Again and again and again. The drivers of the car were kicked. But the 1995 vintage IPCC car remained roadworthy.

There are now new cars and new drivers of the IPCC assessment process. The 1995 “discernible human influence” claim has withstood the test of time. It remains rock-solid.

Time gives one perspective. As I look back on the three decades since Madrid, I feel conflicting emotions. Sadness is one of those emotions. Despite significant scientific advances in identifying human-caused climate change signals, the forces of unreason I encountered in Madrid have not gone away. In the United States, these forces are ascendant. They control many of the levers of power. There is now a staggering disconnect between the on-the-ground reality of anthropogenic climate change and the ignorant dismissal of this reality as a “con job” by the president of the United States. This willful ignorance is already leading to suffering and loss of life. Leaders with the prime directive of keeping their citizens safe from harm are failing at this most basic of responsibilities.

Another emotion is anger. After Madrid, my life was upended. The forces of unreason did not like the “discernible human influence” finding. It was bad for business. So they engaged in a scorched-earth strategy. I was investigated by Congress. There were calls for my dismissal with prejudice from my position at Lawrence Livermore National Lab. I was falsely accused of “scientific cleansing” of chapter 8 of the 1995 IPCC report, and of “political tampering” with the report. I spent years setting the record straight. My marriage failed. Those post-Madrid years were difficult for me and for my son, as the plays KYOTO and Smoking Guns have explained.

Some of that anger is still there. Participating in the 1995 IPCC report had personal cost. But the anger is tempered by another emotion: gratitude. I’m profoundly grateful that I had the opportunity, back in 1995, to work on science that matters to all of us. To work on writing those 12 simple but powerful words. To collaborate with brilliant women and men on the task of trying to understand Earth’s climate system, and our role in it. I’m profoundly grateful that I’ve had the opportunity to use my voice. To speak science to power. To defend scientific understanding. To advocate for continued efforts to measure, monitor, and model changes in climate.

“Flow” won the Oscar for best animated feature in 2025. It portrays a cat, dogs, a capybara, a lemur, and a secretary bird in a drowned world, trying to survive an apocalyptic flood in the same boat. Survival requires overcoming their differences. As the Latvian director of “Flow,” Gints Zilbalodis, noted in his Oscar acceptance speech, “We are all in the same boat and must overcome our differences to find ways to work together.” In 2025, thirty years after learning that human actions are flooding our own world, those sentiments ring true.

*Ben Santer is a Professor in the School of Environmental Sciences at the University of East Anglia. He is a member of the U.S. National Academy of Sciences, a John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Fellow, and a contributor to all six scientific assessment reports of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

.

We remind our readers that publication of articles on our site does not mean that we agree with what is written. Our policy is to publish anything which we consider of interest, so as to assist our readers in forming their opinions. Sometimes we even publish articles with which we totally disagree, since we believe it is important for our readers to be informed on as wide a spectrum of views as possible.