By Herman Michiel and Klaus Dräger (*)

November 2020

When the European Commission finally realized that something serious was going on with corona, it launched, among other things, an initiative to support short-time work schemes, as Germany did as a reaction to the 2007/9 ‘financial crisis’. Similar measures were introduced in many EU countries at national level to cope with the economic and social effects of the pandemic.

On 2 April the EU launched SURE [i]. The idea was that member states could take out cheap loans to financially support temporary short-time work schemes. After all, many companies are much beyond of their former capacity (in some sectors they even lost up to 80 percent of their former business). Without government support, so goes their tale, they would have to shed many employees towards unemployment.

Maybe you say: loans do not really support governments, who can borrow anyway, and borrowing means higher public debt. The fact is, however, that the Commission (EC), as the executive body of the EU, can borrow more cheaply than many member states. Since the financial crisis, we know that this is even true within the euro-zone, where, for example, Greece has to pay much more for a government loan than Germany.

In financial jargon one speaks of the spread, the difference compared to Germany’s interest rates for government bonds. It would be different if those member states could borrow directly from the European Central Bank (ECB), which could charge the same low rate for everyone. But the EU treaties explicitly forbid such a thing. Governments therefore have to borrow from private banks and financial institutions, which charge a ‘risk premium’ that is all the higher the more difficult a country’s economic situation is. If the European Commission now presents its SURE initiative (and other similar loans in the context of the corona recovery policy) as a shining example of European ‘solidarity’, this is only a very partial correction to a fundamentally non-solidary construction based on market discipline.

Six months to respond to an emergency situation

Another consequence of the ban on ECB lending to member states is that cumbersome, time-consuming manoeuvres have to be performed now that the EU is (for the first time, and breaking its own rules) taking out loans to pass them on to member states. The ECB can make billions available to banks in a jiffy, as happens with ‘QE’ (quantitative easing). The SURE initiative, on the other hand, officially launched on 2 April, took until the end of October, i.e. more than half a year, to pass on the first ‘solidarity-based’ loans to Italy (10 billion), Spain (6 billion) and Poland (1 billion). So the ‘support in an emergency’ comes rather late.

Why is this? In order to borrow, the Commission first had to provide a ‘guarantee’. To this end, all 27 member states had to agree to guarantee a total amount of € 25 billion, in proportion to the national income of each member state. It was only on 22 September that the Commission was able to report that this operation had been completed, although only commitments, not payments, had to be made. With this guarantee in its pocket, the Commission was then able to borrow an amount four times higher (by a so-called leveraging operation). In order to do this, a syndicate of banks had to be called upon to issue bonds, an operation that took place via Barclays, BNP Paribas, Deutsche Bank, Nomura and UniCredit. For future loans (probably one more in 2020, the next in 2021), this procedure will have to be gone through again.

Selective interests from the EU’s member states

In a sense, for EU standards, the gathering of the commitments of the 27 member states was a ‘success’. Indeed, in countries where fulminating against the ‘debt union’ is part of the identity of a number of parties, political riots may arise around it. This cape was apparently taken. On 22 September, the Commission rejoiced that “the voluntary commitment of guarantees is an important expression of solidarity in the face of an unprecedented crisis”. When, a month later, a bank consortium, for an unknown fee, sold the ‘social bonds’ in no time and under impetuous enthusiasm from investors, it once again gave rise to enthusiastic statements from the Commission. After all, this enthusiasm proves the great confidence that the markets place in the creditworthiness of the EU…

In the meantime, the Commission published an overview of the loan amounts which could possibly be requested by various countries:

It will be noted that a whole series of countries (Germany, the Netherlands, Austria, Denmark, Finland, …) are missing. There is also a good reason for this: they borrow more cheaply on the market. According to the Financial Times (19 October), the Commission lent to approximately minus 0.24% [ii]. Belgium seems to be in an intermediate position, hoping to take some advantage of a ‘European’ loan.

All in all, if we look at the SURE programme globally, there is little reason to speak of a success of ‘Europe and its values of solidarity’. First and foremost, it concerns loans, which will be paid for by the national states and therefore largely by the working population. Secondly, as already mentioned, it is at most a correction to the self-imposed ban on direct loans by the ECB to the member states. Furthermore, one cannot speak of an emergency intervention when it takes more than six months to take a limited initiative in a dramatic context. After all, this is limited in any case: €100 billion, of which only €17 billion are disbursed now, while Europe is plunged into a second corona wave. One hundred billion is ultimately less than 1% of EU GDP.

So we shall see what really will happen. Perhaps the current governments of e.g. Italy, Spain and Portugal have become more desperate because of the second corona lockdown in their respective countries and are now willing to take up the SURE loans (which they did not not touch upon before). The situation in Italy is indeed very desperate. Maybe also other poorer countries will apply for these loans (e.g. Romania). However, the European Central Bank may act as a ‘counterweight’ to ‘light Keynesian spending’.

… enthusiasm among investors?

If the EU speaks of an enormous success to gather support from financial markets for its SURE loan programme – this is true. Bonds were only offered for €17 billion, but the overwhelming demand amounted to €233 billion… The call was outstripped 13 times, and this at a negative interest rate!

This points to one of the great contradictions of neoliberal capitalism, and of the EU in particular. Since the financial crisis broke out 12 years ago, it has never been overcome. Investments are lagging behind, companies and financial institutions are sitting on a phenomenal mountain of money. But they see too few profit opportunities and an uncertain future. The ECB tried to do something about this by pumping thousands of billions of QE money into the system [iii].

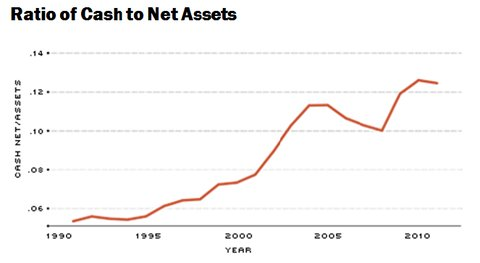

Despite all these central bank ‘incentives’, companies and investors were building up even larger ‘piggy & shadow bank operations’. Instead of investing, they were engaging in further financialization such as share repurchases, financial investments, fat payouts to shareholders – and most notably, hoarding cash. Never before has the equity of German companies been so large, writes Thomas Fricke in Wenn Unternehmer zu viel Geld haben . According to Fricke, ‘corporate liquid assets’ in Germany rose from some 6 per cent of GDP at the time of German ‘reunification’ (1990) to some 15 per cent in 2013. The same trend could be oberserved world wide – also in the U.S., Japan etc. – from the 1990ies onwards.

The increasing amount of cash in the assets of American non-financial firms, 1990-2012. Source: Federal Reserve of St. Louis Compustat Data, 2012.

Thus one arrives at the absurd situation that now central bank and government money is lent at negative interest rates, that thousands of billions are made available to companies and banks – but these are still hesitant to invest (in particular towards the social and environmental transitions, which are desperately needed). So the ‘market engine’ does not work, and the ECB does not even manage to reach its target of close to 2% inflation. Instead, the EU economy is very close to a deflationary spiral, with all its negative consequences.

The benefits of SURE: compassionate neo-liberalism at work

SURE is presented as a social program that allows employees to keep their jobs in spite of the corona crisis. That investors also benefit from it, some will present as a win-win operation. However, the upshot is this: ‘tax payers’ (that is the ‘state’) bail out the corporates and provide the monies to them to keep workers financially somehow afloat.

The hope is: when a recovery should set in, corporations can rely on a qualified workforce that helps them to again boost their business opportunities. This may be also good for the work force – at least they do not immediately become unemployed (as in former times, such as the 1920ies/30ies). But the hardships (of income loss etc.) are imposed on the workforce – whereas the big corporations nearly get any state support which they demand.

So, if one looks at the broader picture, it is again – as was the case during the financial crisis – national governments that have to jump into the breach when the profit prospects of the private sector are threatened. Since national government debts and deficits have not yet recovered at all from the financial crisis, a disaster scenario is being built up here for many decades to come.

Shortfalls in national finances are always paid for by the working class, whether by wage restraint, higher taxes or reduced social security benefits. And this applies not only to the SURE program, but to all corona repair measures taken by the national and European authorities. Taking on more public debt, making wells to fill them, will take revenge on the working class.

Alternatives?

Monetary financing seems a better idea: the ECB makes loans available to the member states with zero interest rate and a term of, for example, 1,000 years, which means that they do not have to be repaid. Sovereign debts do not increase. This is the idea behind the ‘perpetual bonds’ or the so-called ‘consols’ that were previously discussed [iv].

Of course this cannot be reconciled with the European treaties, but we are also not looking for a sustainable solution within these treaties, because it cannot be found there. But there is another objection. It is true that public debt does not increase, but once again a public instrument (the monetary power) is used to save the profit prospects of the private sector. This is reprehensible, not only from the point of view of social justice, but also from the point of view of economic efficiency.Why?

After all, apart from more sovereign debt and monetary financing, there is a third possibility: get the money where it is via taxes. This is, of course, more socially just, and it also addresses the concerns expressed now even by the IMF and the World Bank, namely the worldwide formidable inequality, the still growing gap between rich and poor. But as said, such an approach is also economically more efficient.

The aforementioned Thomas Fricke attributes the ‘hoardiness’ of capital owners to tax reforms, among other things, which make such practices more attractive. The logical consequence is that a heavy tax on the hoarded money of the financial actors will bring that money back into circulation. It will inevitably be invested rather than hoarded. Part of the investment may go to the labour force, a reduction in working hours without loss of wages, an increase in wages, which, unlike speculative investments, will return to the economic circuit in the shortest possible time, and in the long run cause some inflation (which the ECB is so feverishly and vainly looking for). Another part can ensure sustainable development, for example by investing in a fossil-free production apparatus.

The fiscal approach, as opposed to the monetary one, also has the advantage of being able to ensure redistribution. This also meets the objection that not all companies are equal, that some survive with difficulty and others do not know what to do with their money. An appropriate fiscal policy can do a lot about this. It would run counter to the neo-liberal thinking of the EU, but it hasn’t been said often enough: exceptional problems require exceptional measures.

So there are indeed alternatives to the EU’s market-oriented policy. However, there is no alternative to an intense, protracted, internationalist struggle to push through alternatives.

(*) Klaus Dräger was a longtime political adviser for the left-wing group in the European Parliament (GUE/NGL) on employment and social affairs. Herman Michiel is an editor of the Dutch-Flemish website Ander Europa.

[i] SURE: temporary Support to mitigate Unemployment Risks in an Emergency

[ii] A negative interest means that the financial markets are willing to pay a premium to get ‘safe’ bonds in their possession. This kind of upside-down world we are gradually getting used to, and it points to the fundamental crisis of the capitalist economy.

[iii] This is not a literary exaggeration. By the end of 2018, the ECB’s QE program (quantitative easing) had provided cheap money to the tune of €2600 billion, and a new program was launched in 2019.

[iv] See for example When European leaders speak of offering grants…