From California to Massachusetts, a grassroots revolt from the left is wresting control of the party away from the corporate establishment.

When Kimberly Ellis entered the contest for California Democratic Party (CDP) chair in 2015, she adopted a slogan from Shirley Chisholm’s groundbreaking 1972 presidential campaign, “Unbought and Unbossed.” Four years before becoming the first woman and the first African American to run for the Democratic presidential nomination, Chisholm had defied the Democratic machine “bosses” in Brooklyn to win a House seat.

For Ellis, the slogan was both a nod to Chisholm and a dig at the bossed and bought character of the Democratic Party. She and her opponent in the race, Eric Bauman, agreed on a range of progressive policies, like single-payer healthcare and a minimum wage of at least $15. The heart of their dispute was the influence of economic elites and the political establishment over the party. Ellis, the former head of an organization devoted to recruiting women to enter politics, has long advocated reducing the influence of lobbyists and corporate money, and broadening the base by building a network of organizers and activists.

“I believe the CDP should hire organizers, not build an institute,” she noted in a statement of her principles, taking a swipe at Bauman’s idea of building a think tank devoted to progressive ideas. In her pitch at the state convention, Ellis told delegates, “If we want people to fight for the Democratic Party, we have to give them a Democratic Party worth fighting for.”

Bauman is a longtime party insider—chair of the Los Angeles County Democratic Party since 2000, vice chair of the state party since 2009 and senior adviser to the speaker of the state Assembly, Anthony Rendon. He also runs a political consulting firm, VictoryLand Partners. This became a major issue in the race for state chair when it emerged that VictoryLand had received more than $100,000 from pharmaceutical companies that opposed a ballot measure designed to cap prescription drug prices in California. Bauman, in his defense, said, “I’m certainly not using my personal influence with anybody on this matter.”

Because it was a ballot measure, legislators weren’t directly complicit in its defeat, but the ties between Rendon, Bauman and VictoryLand looked bad. For Ellis supporters, the issue came to sum up the rot in the Democratic Party. At the convention’s general assembly on Saturday, May 20, they frequently interrupted and chanted over speakers. Ellis supporters formed a ring around the event hall, many of them clad in bright pink “Unbought Unbossed” T-shirts, chanting “Kim-ber-ly!” The retiring state chair, 84-year-old John Burton, eventually took the microphone and invited the protesters to “sit the fuck down, please” and show “some fucking courtesy.”

Later that day, when the votes were counted and word spread that Ellis had fallen short by 62 ballots, out of about 3,000 cast—a margin so close that the Ellis camp challenged the result, triggering a review still ongoing—it seemed to many of her supporters like a rerun of the same old, same old. Bernie vs. Hillary. Ellison vs. Perez. Close but not quite. For all the passion of the insurgents, the establishment still gripped the reins of power. One Ellis supporter at the convention, Wendy Ruiz, a delegate from South Los Angeles, expressed her frustration and disappointment with the disconnect between the party’s words and deeds. “At what point are you going to step up for us and do what you said that you would?” she asked.

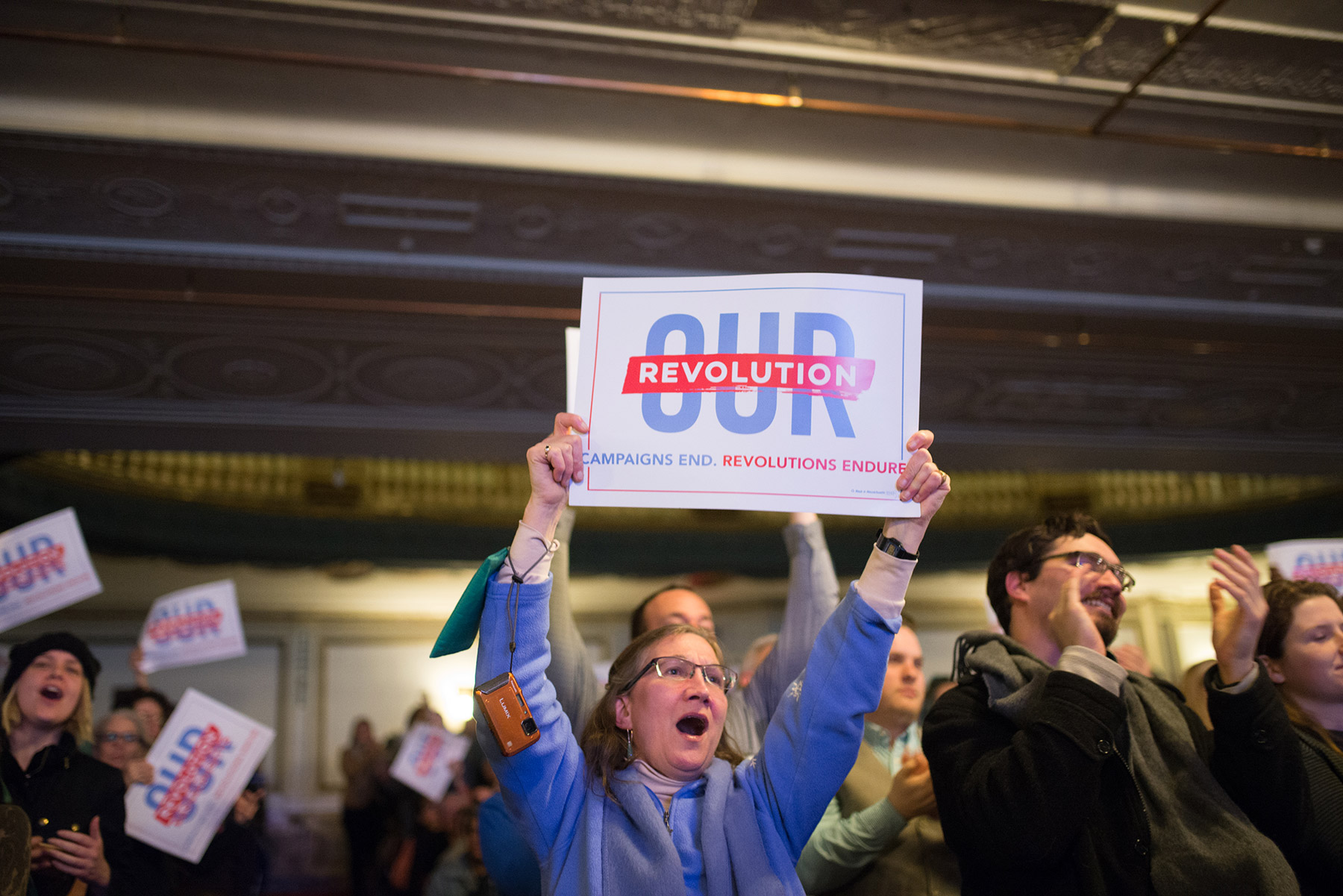

As Democrats gear up for the 2018 election cycle, that disconnect is fueling passionate efforts to transform the party. Whether this uprising by the party’s progressive wing is a false start or the start of a revolution, it is without doubt the most serious fissure in the party since its centrist and leftist wings came to blows over the Vietnam War in 1968—the year that Shirley Chisholm was elected to Congress as an anti-war Democrat.

The race between Bauman and Ellis was never supposed to be so close. Ellis came within striking distance only because, a year ago, progressives set their sights on changing the CDP leadership.

The plan took shape among Bernie Sanders delegates at the 2016 Democratic National Convention in Philadelphia. It gained momentum when the California Nurses Association (CNA)—a strong advocate for single-payer healthcare—got behind the Ellis nomination, along with the Consumer Attorneys of California and (late in the process) Our Revolution, the organization founded in September 2016 to carry forward Bernie Sanders’ “political revolution.” Victory became a possibility in January when progressives turned out in strong numbers for delegate elections across the state and won a majority of the races.

But elected delegates add up to only a third of the total. Two-thirds of delegates are appointed by party organizations, officials and politicians. That un-democratic imbalance sums up the heart of the dispute between Bauman and Ellis: whether party leaders or the party’s activist base will hold the power.

The answer has political implications that aren’t immediately obvious. For example, progressives in California have been pushing for years to give the party’s platform more power. That was a centerpiece of Ellis’ campaign. “If there’s no enforcement mechanism, then what good is the platform?” says Karen Bernal, who served as an adviser to the Ellis campaign and was elected chair of the Progressive Caucus at May’s convention. “If there’s actually no teeth behind it—if we can’t deny an endorsement over it—then, honestly, it’s meaningless.” The party leadership has consistently resisted any reforms that would make the platform more binding.

Bernal says the progressive coalition that fought to elect Ellis and push through such reforms understood the stakes. “We’re the largest state Democratic Party,” she says. “We knew that the rest of the country would be watching.”

But if one takeaway of the struggle for the CDP is that the Democratic establishment narrowly won yet again, another is that “the resistance” won’t be limited to fighting the GOP—and it won’t be content to play defense.

“There’s a difference in the kind of resistance we’re talking about, and the kind of resistance you often see promoted as ‘the resistance’ by groups such as MoveOn.org or Indivisible,” Bernal says. “Their main thing is to resist Trump. But I’m not really sure they understand what that means. For the Berners who’ve gone into the party, they’re very clear about the agenda, which is an anti-corporate, anti-neoliberal agenda. Here in California, we know what resistance means to us. It doesn’t mean saving the ACA. It means replacing it with single payer.”

At the convention, when the CDP establishment tried to paper over intra-party tensions by talking about “the resistance” to Donald Trump, Ellis supporters weren’t buying it. “You know what I want to resist?” said RoseAnn DeMoro, executive director of the CNA, to a group of Ellis supporters on the eve of the convention. “Corporate Democrats.” The line drew huge cheers.

CNA was vocal in its support of both single-payer healthcare and Ellis. DeMoro warned in a speech to the general session that if Democrats “dismiss progressive values and reinforce the status quo, don’t assume that activists in California and around this country are going to stay with the Democratic Party.”

If the movement to elect Ellis had its origins among Sanders’ DNC delegates, Ellis’ crossover appeal shattered any simple Bernie vs. Hillary assumptions. Chants of “Bernie!” became a rallying cry among Ellis supporters—many of whom had war stories about volunteering for his campaign—but Ellis herself had, in fact, endorsed Clinton. What bonded her supporters, more than their enthusiasm for Sanders or Clinton, was a fierce passion for reforming the Democratic Party. For this wing of the resistance, countering the influence of big money in politics is fundamental. Democrats don’t get a pass because they pay lip service to progressive values.

“The corporate interests have been able to buy the politics of this country and therefore buy the government,” says Jim Hightower, a board member of Our Revolution and part of the leadership of Our Revolution Texas. “The single most important thing to me about the Bernie campaign was that he put the lie to the Democratic claim that we cannot unilaterally disarm; we have to raise the big money in order to deal with the Republicans. Well, Bernie raised something like $130 million from small donors, and the average donation was $27.”

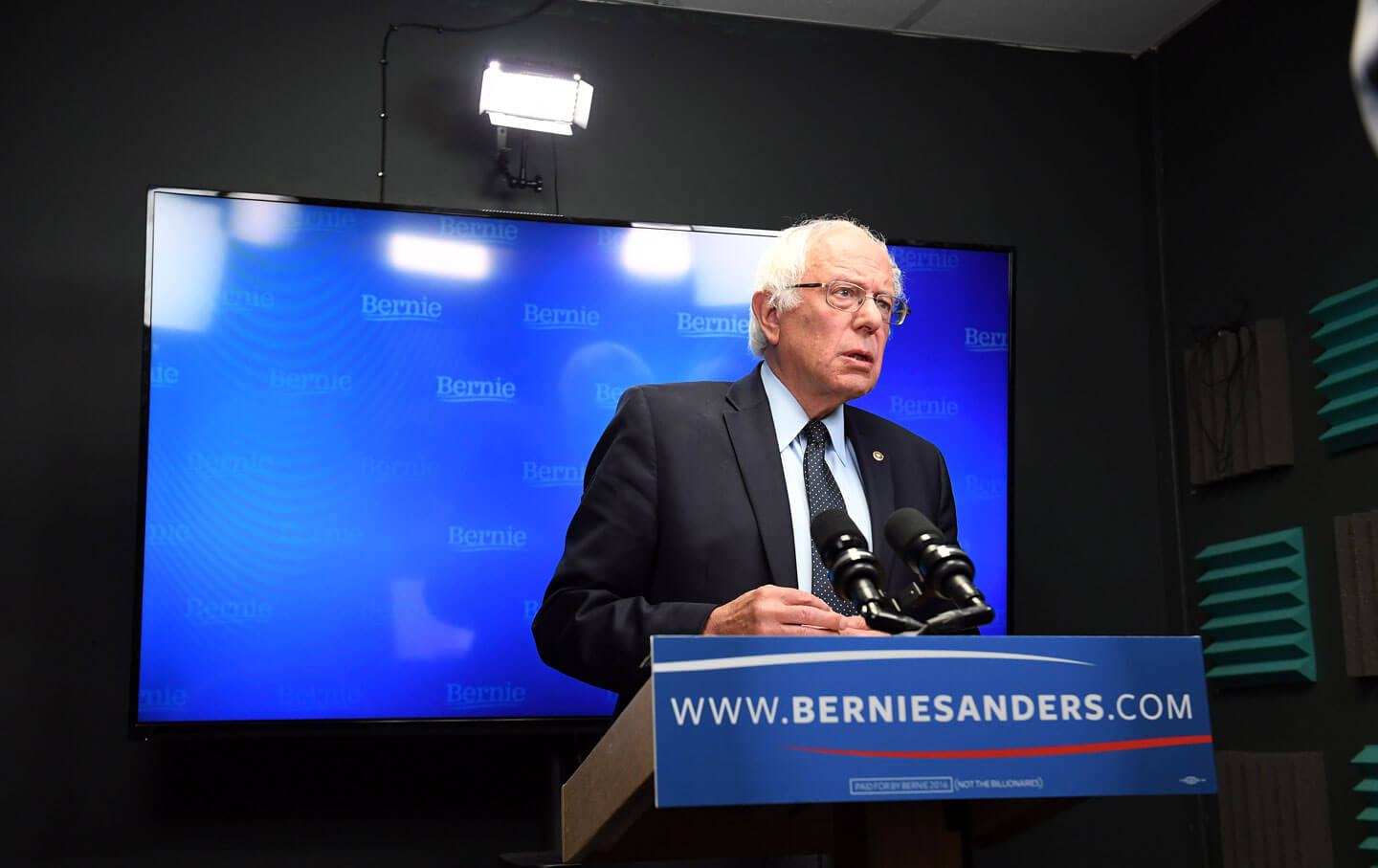

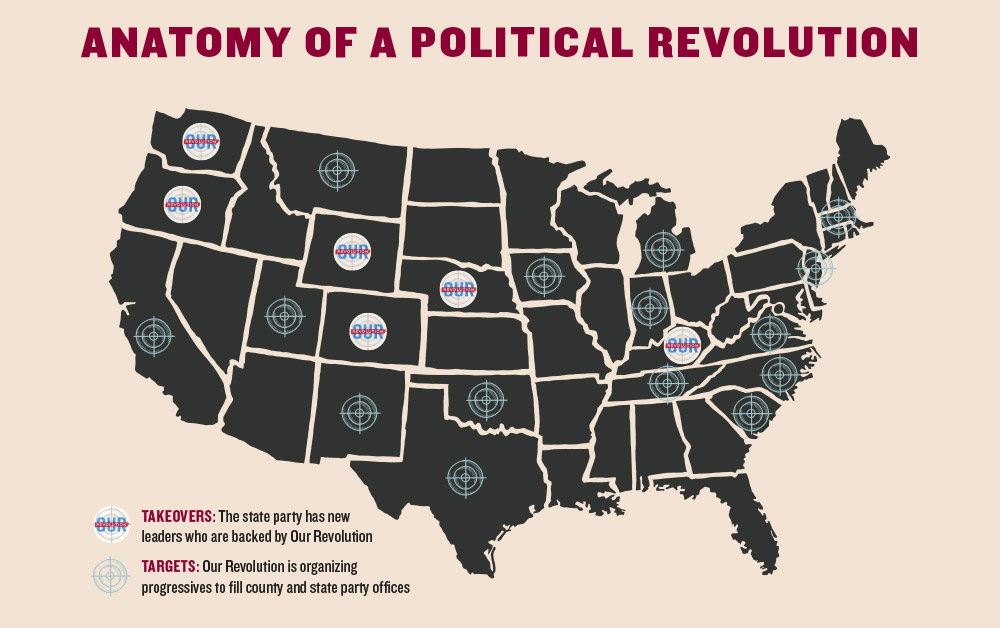

Pushing the Democratic Party to the left is a longstanding goal of progressives, of course. What distinguishes this moment is the momentum created by a combination of loathing for Trump and enthusiasm for Sanders’ call for political revolution. A wide range of progressive groups are involved on the local level, but Our Revolution has emerged as the nationwide coordinator. Within the past year, progressives associated with Sanders or Our Revolution have become party chairs in Colorado, Nebraska, Washington and Wyoming.

There was no contest for the chair at the Michigan Democratic convention in February, but about 5,000 people showed up—an unusually high turnout, fueled in large part by the organizing work of Sanders-inspired groups such as Michigan for Revolution. Progressives won caucus races and seats on the state central committee. As one member of Michigan for Revolution told the Detroit News, “Right now it’s a party that’s dominated by elite stakeholders and donors, and that’s not the way it should be.”

“It’s a big structural fight that we’re in,” says Hightower. “We’ve got to have our own political organization with the fundraising capacity to take on the moneyed interests and the plutocractic interests. And that possibility is what excites people.”

Progressive reformers are focusing on both policy and process. On policy, single-payer healthcare and a $15 minimum wage are key rallying points. On process, the reformers are pushing for a devolution of power away from party bureaucracies—and toward the base—by increasing the percentage of the leadership that is elected rather than appointed. They also want to diminish the power of special interests through rigorous disclosure requirements on campaign contributions and through bans on donations from corporate PACs to state parties. The objective? Make the parties more responsive to the needs of people rather than corporations, and hold politicians accountable to the party platforms, which tend to be to the left of the policies many Democrats campaign on.

“If you’re taking that corporate check,” says Hightower, “you’re not pushing a $15 minimum wage; you’re not pushing Medicare for all; you’re not pushing free higher education. You’re going along with the corporate agenda.”

Our Revolution Texas is in the process of creating the infrastructure to challenge the established state party. It has divided the state into 11 regions, and the regional chapters will recruit and train candidates to run in local, state and congressional elections next year. Our Revolution Texas is also encouraging progressives to become precinct chairs in their local Democratic Party chapters. The party is so hollowed out in the state that taking it over is mainly a matter of showing up.

“In probably half of the precincts in Texas, there’s no precinct chair,” Hightower says. “So we’re going to fill as many of those as we can.” The precinct chairs elect the county chairs, who in turn choose the state party chair.

In January, Our Revolution Texas became the national organization’s first state affiliate. Hightower says it’s filling a vacuum in the state left by the Democratic Party’s reliance on corporate donors and top-down party decision making. “Democrats gave up on door-to-door and precinct-to-precinct organizing,” he says. “And we surrendered our populist voice.”

In Texas, the corrosive influence of corporate money on the Democratic Party is especially clear in its relationship to oil and gas interests. Henry Cuellar, who represents a U.S. House district in the oil-rich southern part of the state, took in upwards of $165,000 from that industry in the 2015-16 election cycle—more than any other Democratic member of Congress. The League of Conservation Voters gave Cuellar a score of 26 out of 100 for his environmental voting record in the 2015-16 cycle.

Hightower cites fracking as an example of a progressive issue that could revitalize the party and help it win in rural areas the GOP has come to dominate. The digging of fracking wells creates only temporary jobs, sometimes filled by non-locals, he says, and, “We’re left with the noise, the pollution, the methane, the illnesses, the destruction of the roads, the total usurpation of the water.” If Democrats took it on as an issue, then “people would say, ‘All right. There’s somebody standing up.’ ”

In the 2014 congressional election, Texas had the third-lowest voter turnout in the nation: just 28 percent of eligible voters. “It’s not that Democrats turned right-wing,” Hightower says. “They quit voting. If they hear candidates and political organizations talking about the things they care about, they’ll respond.”

If the weakness of the Democratic Party in Texas and across much of the West makes the state chapters ripe for a takeover, it’s a different story in the East, especially the Northeast, where the party is strong and has a reputation for being relatively progressive. As in California, though, there is an entrenched establishment that resists reform.“It’s very clearly an insiders’ club, and there are all sorts of hoops to jump through,” says Matt Miller, an activist based in Somerville, Mass., and a member of Our Revolution Massachusetts, which—along with Progressive Democrats of America, Progressive Massachusetts and other groups—set its sights on injecting a strong progressive presence into the Massachusetts Democratic Party convention on June 3 (read an update here).

Just getting basic information “about when caucuses are held and what you have to do to be elected” was a struggle, Miller says. Nevertheless, he and other progressives persisted.

For months, they carried out a methodical plan. First, get progressives to show up at the caucus meetings—held in February, March and April—to elect progressive convention delegates. They succeeded in electing about 700 of 4,529 total delegates. Second, organize strong turnout at a series of platform committee hearings in April and May. The resultant draft platform, released in late May, contained many of their demands, including single-payer healthcare, a $15 minimum wage and paid family leave.

The final step is to get delegates to attend the convention, where, with 200 signatures on a petition, they can force a vote on an amendment to the platform—to prohibit gerrymandering, for example, or to implement ranked-choice voting. In early May, more than 150 of the 700 Our Revolution delegates attended a special training session to make a game plan. In addition to pushing the party’s platform further left, they will call for the democratic election of superdelegates to the Democratic National Convention—currently selected by the DNC and approved by the state party chair—along with the restriction or elimination of donations from corporate PACs.

In Massachusetts, as in California, there is a sense that corporate money and top-down control have warped the party’s priorities and created a disconnect between ideals and actions.

“The party is at a real fork in the road,” says Rand Wilson, a labor organizer for SEIU Local 888 and a member of both Our Revolution Massachusetts and Labor for Our Revolution. “We have to choose between building a party for the working class or for the 1%. The lines are being pretty starkly drawn.”

At the 2016 Democratic National Convention, Wilson says, he attended a breakfast for the Massachusetts delegation that, unbeknownst to him, was sponsored by a charter school organization. Charters were a divisive issue in the state at the time. The state Senate, controlled by Democrats, had recently passed a bill designed to lift the cap on the number of charter schools. It eventually became a ballot measure and was defeated by Massachusetts voters that November. Support for the charter school expansion came from corporations and the financial industry, while teachers unions fiercely opposed it.

“I jumped up and said, ‘Charter schools suck!’ and I walked out,” Wilson says. “I left there going, ‘Wow, there’s really something wrong with a party that would invite and accept funding for a breakfast from the charter school people.’ It was emblematic of a Democratic Party that is clearly for sale.”

Like many progressives, Wilson has a skeptical stance toward the Democratic Party. He was a lifelong Independent until he registered as a Democrat in 2015, primarily because he wanted to go to the national convention and support Sanders.

“The party structure and democratizing it—that’s all noble, but I wonder if it would be better to just shift the actual power,” says Matt Miller, who worked on a Democratic primary race in 2015. “We knocked out a crappy Democrat and replaced him with a former Occupy guy. So I wonder if that’s not a better strategy. But I’m going to try this for as long as it makes sense.”

For many progressives, rather than racking up immediate wins, experimenting with the nature of “the resistance”—figuring out what works over the long run, where to invest resources, and how to relate to and transform the Democratic Party—seems to be what this moment is about.

For her part, Karen Bernal’s experience with the California Democratic State Convention left her feeling “not optimistic” about reforming the CDP, yet more hopeful about the progressive movement generally.

“We’re going from a mentality of protest to learning what it means to seize political power,” she says. “The new people who have come in—they’re getting a boot camp. And that is the lesson. No matter what happens with the Democratic Party, we’re going to have people who are much more savvy about how to resist politically.”

That isn’t to say the fight for the CDP is a lost cause. As with “the resistance” broadly, the path ahead is uncertain. For many in California, the recent loss felt more like the beginning of a journey than its end.

“This is a womb, not a tomb,” says Rochelle Pardue-Okimoto, a nurse and convention delegate who supported Kimberly Ellis. “It’s the rebirth of the Democratic Party. We just have to keep pushing. We all felt bloodied and bruised by this battle, but we can’t give up. We’re changing things.”

Winona Dimeo-Ediger contributed reporting from California.

This piece has been updated to correct the chronology of events at the conference. Ellis supporters ringed the event hall on Saturday, not Friday.

Theo Anderson an In These Times staff writer, has contributed to the magazine since 2010 and is currently a Schumann Center writing fellow. He has a Ph.D. in modern U.S. history from Yale and is working on a book about the intellectual and religious origins of conservatism and progressivism.