Rob Lucas, NLR/Sidecar

January 30, 2026

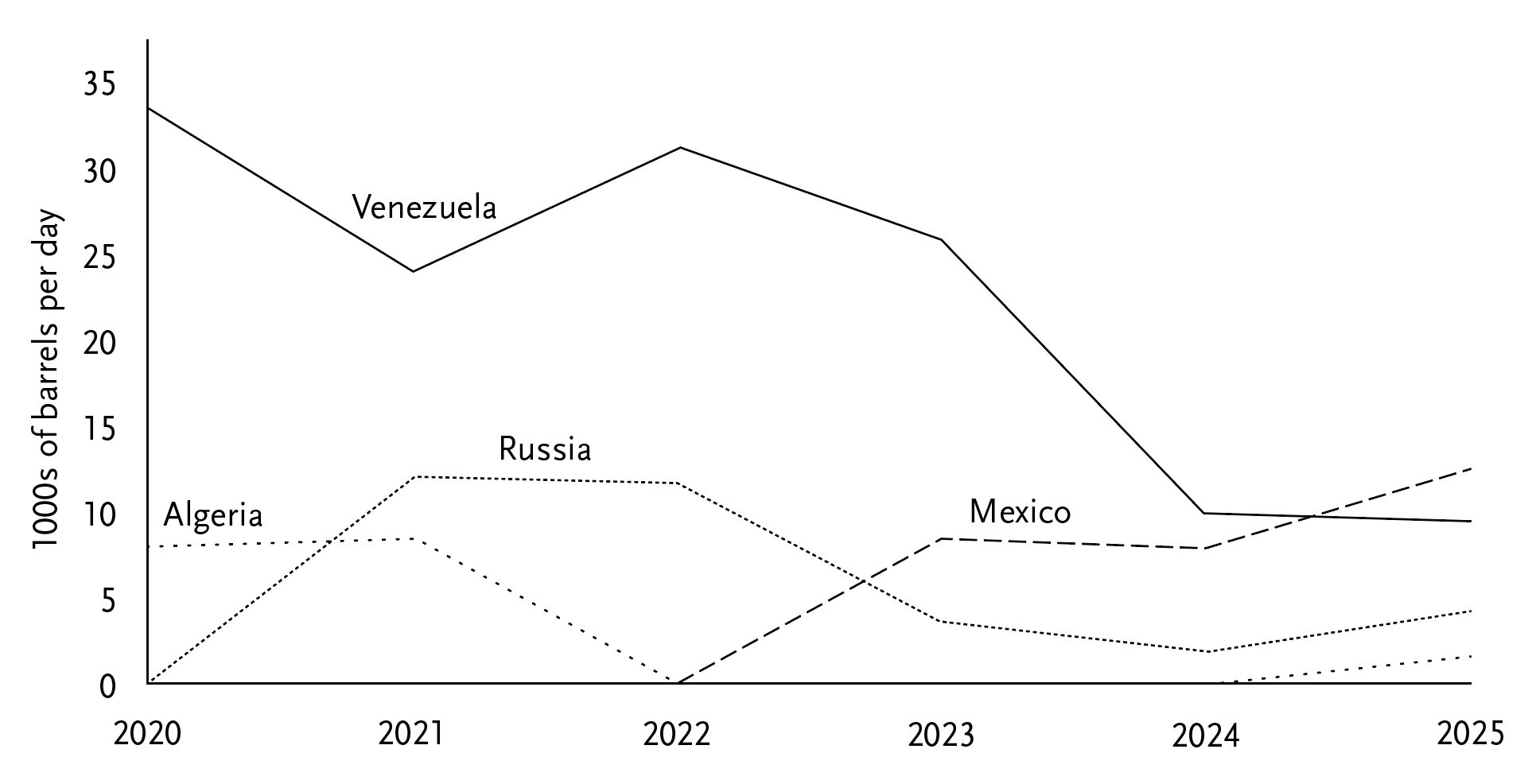

When I last visited Havana, in March 2025, it was in the midst of what was then the worst blackout in years. As the plane approached, the ground below was mostly dark – dotted only by light from the microsistemas which run even in moments of power failure. That Saturday night, the city’s bars were mostly closed, save those that could afford their own generators. By chance, my neighbour for the Atlantic crossing was a talkative engineer from an EU delegation proposing decentralized solar farms and batteries that, he claimed, could solve Cuba’s chronic power-supply problems for the next thirty years. But progress was slow – a matter of years, rather than a short-term fix for the power crisis – and he blamed the bureaucracy. In the meantime, the island-state was still limping along on Venezuelan oil supplies increasingly throttled by US sanctions, while turning to other sources: Mexico, Russia, Algeria; Turkish power barges anchored at Havana injected a little extra into the grid. Cuba has been plagued by blackouts since 2024, when imports of Venezuelan oil dropped precipitously, a problem exacerbated by ageing, largely Soviet-era technology. Limited electricity is rationed through scheduled shutdowns, while momentary excesses of demand are managed by ‘load shedding’ and partial blackouts. Nowhere escapes the power cuts entirely – at points the entire grid has gone down – but outside the capital it’s much worse.

Figure 1: Crude and Petroleum Exports to Cuba since 2020

After a period of relative optimism with the opening under Obama, and Havana’s initiation of a ‘reform’ programme, re-escalation of the blockade under Trump and Biden in a context of compounding disasters – Covid and the collapse of international tourism, global inflation, local macroeconomic disorder, shortages of basic goods, mass youth migration – have left the Cuban state at its weakest since the revolution. Even in the post-Soviet ‘Special Period’, when it also suffered power-supply problems and constraints on the food supply led to outbreaks of previously unknown diseases, the island managed to sustain a growing population; now it is facing demographic collapse. Misfortune upon misfortune, in 2025 an international resurgence of mosquito-borne diseases, chikungunya and dengue, hit a country experiencing medical shortages, as Hurricane Melissa left a trail of destruction in its east. Meanwhile, a menacing US deployment – the largest in the region since the end of the Cold War – was gathering in the Caribbean, summarily executing so-called ‘narcoterrorists’ off the Venezuelan coast. The absurdity of Trump administration claims about the ‘Cartel de los Soles’ as it ramped up pressure on Maduro reinforced a sense that the real goals were unspoken; was Cuba the true target?

Tight relations between the Venezuelan and Cuban states began to form early in the first Chávez presidency, on the basis of shared political convictions and friendship between Chávez and Castro – who, I am told, used to call each other regularly in the early hours to debate world politics and literature. In 2000, the Convenio Integral de Cooperación between the two countries established arrangements according to which Cuba would send medical and technical staff in exchange for oil; treatment by Cuban doctors became an everyday experience in Venezuela. An attempted military coup in 2002, recall vote in 2004 and lost constitutional referendum in 2007 successively drove Chávez to call on Cuban support to reinforce his rule through restructurings of the military and intelligence services. This is the origin of the Cuban bodyguard presence that would be slaughtered in the 3 January kidnap of Maduro. In the fevered imaginings of the Miami right, these arrangements became the basis of a tail-wags-the-dog thesis, according to which the island-nation was the real ruler of a country many times its size in population, land area and wealth. Washington’s overthrow of chavismo could thus implicitly be reconceived as an act of national liberation from Cuban domination.

Since early in his political career, Marco Rubio has burnished his anti-communist credentials for the Miami scene, presenting his parents as refugees from Castro’s Cuba even though they became US residents three years before the revolution. Already during the first Trump Administration – a context receptive to Latin America hawks – he played a role in shaping aggressive policies towards Caracas and Havana. It was thus expected that further pressure on both would result from his installation as Secretary of State. Since the post-9/11 targeting of Al Qaeda financing, the US has honed its tools of economic warfare, enlisting Treasury and Commerce departments to wreak havoc on the economies of designated opponents – North Korea, Iran, Russia, Venezuela – by shutting them out of global financial markets, dollar-clearing mechanisms, the SWIFT payments system, or simply by making it too risky for banks to deal with them. Typical results are inflation, currency depreciation and shortages. These have become weapons of choice in a period when direct military interventions have lost their lustre, given the disaster-zone left by the invasion of Iraq and the humiliation of losing to the Taliban.

The stated aim of US Cuba sanctions since the early 1960s has been to delegitimize the government by inflicting economic misery on the population; that the hoped-for upheaval is yet to happen two thirds of a century later has prompted little strategic reflection. This arrangement has persisted for so long, apparently, that the voluminous recent sanctions literature struggles to find anything much to say about it; US Cuba policy has been so persistently punitive since the revolution it can seem reasonable to wonder whether there is anything else they can do. Yet Cuba sanctions have changed during the new era of economic warfare, starting with the targeting of the tourism industry in 2003, and continuing with the Trump-Biden reimposition of Title III of the Helms-Burton Act, which aims to deter foreign investment through legal threats. With an interest in geoeconomic ‘chokepoints’ gaining prominence in US foreign policy – and a ‘hemispheric turn’ on the horizon – Cuban dependence on Venezuelan oil offered an obvious focus, and the prospect of killing two birds with one stone. If Cuba has maintained a significant degree of international support, the unloved remnant of official chavismo – reigning undemocratically over a society mired in corruption and its own serial economic crises – was a target that few would mourn internationally, except Cuba.

From 2017 the first Trump Administration ramped up sanctions on Venezuela. But as with Russia, the economic war here has not been a simple matter of old-fashioned blockade – regardless of the recent spectacle of tankers nabbed at sea – for the longstanding imbrication of Venezuelan and US oil sectors persisted in reduced form even under Chávez, while Chevron gained a special dispensation from the Treasury Department to keep operating in Venezuela through the sanctions – an arrangement they were finally instructed to wrap up only in Spring 2025. Due to such complications, US measures have threatened to backfire at points: in one comical misstep, the Russian state, via Rosneft, came close to inheriting an important bit of oil infrastructure in the US through the capsizing of Venezuelan firm PdVSA, of which Rosneft owned a large share, sending Treasury officials scrambling to slam the door.

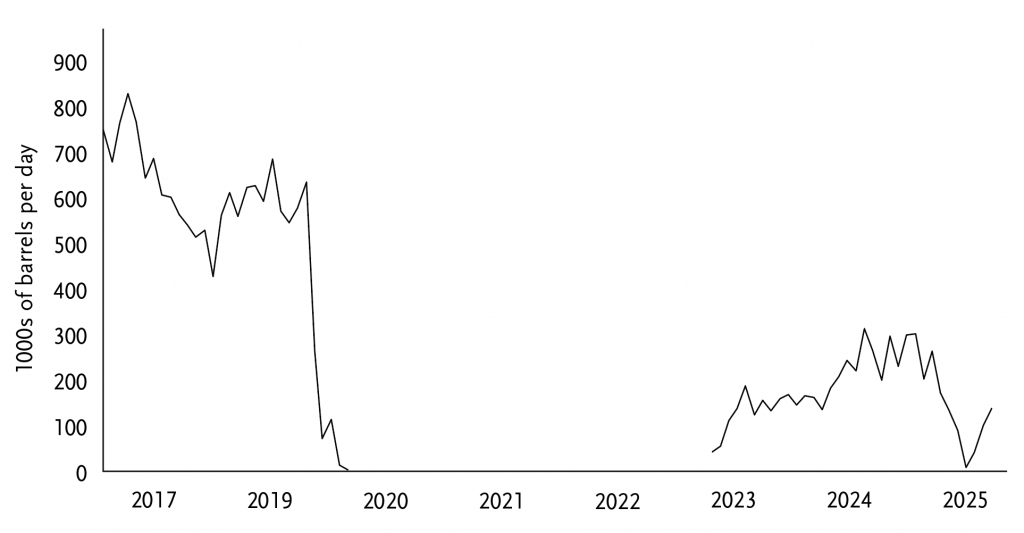

After a 2020–2022 pause, US imports of Venezuelan crude resumed in 2023 – well before the recent military intervention – at a rate that was orders of magnitude above what Venezuela was sending to Cuba (compare Figure 2, below, and Figure 1, above). Rather than simply targeting production, sanctions were – as with Russia – applied to shipping, creating a distinction that the US itself has policed between licit and illicit tankers. There is no question about which side of this line shipments to Cuba fell: part of the campaign of naval pressure on Maduro involved the December seizure of a Cuba-bound shipment, in a year when the US itself had already accepted vastly more Venezuelan crude. US sanctions officials do not generally trouble themselves much with reflections on the coherence of the legalistic and moral discourses that accompany their acts of economic warfare.

Figure 2: US Imports of Venezuelan Crude since 2017

In 2025, Mexico displaced Venezuela as Cuba’s main supplier, likely offering some oil at a discount or for free, though at levels well below what Caracas had been sending previously. Now even this is in doubt, with Mexico suspending shipments – a decision that Sheinbaum has claimed was ‘sovereign’, although the threatening US posture towards Mexico at a moment when the US-Mexico-Canada free trade agreement is up for review is relevant context. As this article went to press, the Trump administration had just declared that it would impose tariffs on any country providing oil, on the patently ridiculous basis that Cuba had taken ‘extraordinary actions that harm and threaten’ the US; and that it ‘supports terrorism and destabilizes the region through migration and violence’.

The noose is tightening, but Cuba does have some domestic crude supply and refining capacity, which makes up a non-negligible share of what it consumes – 41% in 2023, even before the collapse in Venezuelan supplies; apparently enough to support the creaking thermoelectric plants that form the backbone of the Cuban grid. It also has natural gas, which accounted for 12.6% of electricity generation and 23.6% of domestic energy production in 2023; combined, these fossil fuels alone amount to a slim majority of energy production from ‘sovereign’ sources. Cuba may thus have some capacity to resist even a total fuel embargo, but this will be challenging nonetheless: it should not be downplayed that in the same year the majority of Cuba’s oil supply – which accounts for 84% of its total energy use – came from Venezuela.

Might renewables come to the rescue? ‘Much as they would like to, they can’t take the sun away’, said one official I queried in 2025. China has recently been financing solar projects throughout the country, and it is imaginable that the situation could be transformed relatively quickly: in 2023 total electricity generated amounted to 54,304 MWh per day, of which just 457.5 MWh, 0.8%, came from solar, but solar capacity is now apparently 3250 MWh per day – a 610% increase in just a couple of years. While still a fairly small part of what is needed (about 6% of the 2023 total), this figure is forecast to triple, at minimum, by 2030, putting solar at around 18% of the total. The combined share of renewables in the energy mix had already risen significantly, to 5.2% by 2021. While not yet an energy revolution, there are thus signs here that a relatively rapid transition may be possible, with solar increasingly filling the gap left by non-sovereign sources of energy. It may be that the current energy crisis thus represents a pivotal juncture in US-Cuba relations, between the chokepoint of Venezuelan oil-dependence and a green alternative to it.

The question is whether the Cuban state has the capacity to hold out long enough to reach new strategic terrain. As well as Trump’s widely-reported 11 January demand that Cuba ‘make a deal, BEFORE IT IS TOO LATE’, and despite maintaining the usual menacing tone, he has indicated a certain ambivalence about US prospects here – perhaps informed by some intelligence assessment:

I don’t think you can have much more pressure, other than going in and blasting the hell out of the place. Look, they are—their whole lifeblood, their whole life was Venezuela. [. . .] I think that Cuba is hanging by a thread. [. . .] Look, Cuba got all of its money for protecting. They were like a protector. They’re tough, strong people. They’re great people. Marco has a little Cuban blood in him. [. . .] I think that Cuba is really in a lot of trouble. But you know, people have been saying that for many years, in all fairness, about Cuba. Cuba has been in trouble for the last 25 years. And you know, they haven’t quite gone down, but I think they’re pretty close of their own volition.

Diminished as it is, it is worth recalling some specifics about Cuba that may cast doubt on prospects for an easy US victory.

It goes without saying that in any straightforward military confrontation, the US would possess absolutely overwhelming destructive capacities; it could very easily ‘blast the hell out of the place’. But the US has a poor track record when it comes to actually winning even small wars – something that may even be related to its reliance on technological superiority. What’s more, its population is generally well to the left of the Miami lobby when it comes to Cuba policy: a clear majority supported the Obama-era opening and the ending of sanctions. Cuba, for its part, has a small and decrepit – mostly Soviet-era – arsenal, with some more recent Russian supplies. On a global level though, its military spending is relatively high: 4.2% of GDP in 2020, on the CIA’s last published estimate (though it is worth noting that the GDP share here may be partly the result of prioritizing military spending in a context of shrunken total output). According to Global Firepower’s 2025 report, its defence budget was $4.5 billion – a ranking of 54 out of 145 countries: quite substantial for a poor country with a population of less than 10 million.

Cuba has a history of punching above its weight: the only country of its size with a record of successful foreign military campaigns – undertaken on its own initiative and at the invitation of the national-independence movements in Angola, Guinea-Bissau and Mozambique – not to mention surprising intelligence achievements against the US. Cuba has, of course, been preparing for US invasion more or less since the revolution. Its armed forces have an estimated 50,000 active members and are tightly integrated into civilian Communist Party rule, while a large part of the population is nominally available for call-up. They have a high level of legitimacy among the Cuban population, having been kept out of internal repression, and control the most profitable parts of the economy – tourism, finance, construction, real estate etc. And except for the US base at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba has the island advantage of naturally defensible borders.

While any direct confrontation would clearly be a David and Goliath affair, a straightforward ‘boots on the ground’ approach could thus be costly and unpopular for the US – often deciding factors in war-winning capability. Trump’s appeal to the Cubans to come over ‘of their own volition’ and ‘make a deal’ is thus probably the most realistic path to a US victory. Whether parts of the military, bureaucracy or government might be amenable to such entreaties – as seems to have been the case in Venezuela – is inherently harder to gauge; such things are opaque by nature. The fact that the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias control key parts of the economy in a context of partial liberalization and general crisis perhaps brings with it a risk of corruption. The widespread experience of families split between Cuba and Florida, with the inevitable wealth comparison, may supply a subjective lure for individuals throughout the Cuban state and armed forces.

But one should not underestimate the strength of Cuban nationalism. The nation-state here is something practically sui generis: the delayed product not of elite creole initiatives, as was typically the case in the Americas, but of the tipping over of a conventional independence struggle into a social war for the liberation of slaves, in a late holdout of the Atlantic plantation economy. This gave the Cuban project a social aspect long before Castro, and it was essentially this that was repressed when the US invaded in 1898 – under the guise of supporting the independence of the Cuban people – to stake its claim to Spain’s last colonies and grab much of the local economy. It is for this reason that what Fernando Martínez Heredia termed Cuba’s first and second ‘republics’ proved ultimately unstable: under US domination, they struggled to establish settlements of a sort that could resolve the lingering social demands. While geopolitical pressures have long driven Cuba towards the status of a US protectorate, its social forces – in full cognizance of this – have supplied an important brake. This was the case even under Batista – a moment famously symbolized in The Godfather, Part II, when the mob carves up a cake representing the island.

Such tensions could only ultimately be resolved through a revolution and the consolidation of a peculiar kind of state – internationalist, social, popular – distinct from those typical of its region. The archetypal state-form here is so extroverted and socially divided as to be barely ‘national’ at all: coup-prone, with a small, rich elite controlling large parts of the economy and tending towards alignment with foreign extractive interests; riddled with crime and corruption; only fleetingly democratic if at all. This is a configuration that Cuba largely exited through the revolution, which – despite its leaden, authoritarian-bureaucratic aspects – has maintained an unusual demotic aspect and fitful capacity for mass participation over decades. Cuban identity is a complex thing, given its diasporic spread and the contradiction embodied in the Straits of Florida, but insofar as it is still identified with a territory and a vivid experience of domineering treatment from its northern neighbour, it can easily take on a militant form. Identification with the mambise guerilla; invocation of the machete-charge; rehearsal of ‘patria o muerte’ cries – often performed at the top levels of state, these are not without their residual popular bases. And even in the depths of demoralization after years of crisis and the fading of the revolutionary generation, external threats will be liable to blow oxygen on those embers.

Charles Tilly’s famous claim that ‘war made the state’ has a certain plausibility here. The revolutionary government had to remake the internal repressive apparatuses and external military forces more or less from scratch, under imminent threat of US invasion, and they could do so with a compelling national story – the epic of independence, from Martí to Castro. Under intense pressure, structures were formed to enforce discipline against the conjoined threats of internal counter-revolution and external intervention. It is unsurprising that this would issue in a partially military-authoritarian state: it is worth recalling that France and Britain formed such states in their revolutionary moments – not to mention, of course, the broader experience of communist revolutions in the 20th century. Aspects of Cuba’s state model – monolithism; suspicion of critical currents; cultural intolerance – were later imported from a by-then conservative Soviet Union, but it also preserved an independence and capacity to act differently which were artefacts of its own anti-colonial moment; one cannot simply graft on another state model wholesale without material bases. Indeed, if there has been a significant external influence on the formation of the Cuban state, it is the persistent pressure to which it has been subjected by the US. This has surely heightened tendencies towards authoritarian consolidation, and hampered prospects for full democratic participation, while US acceptance of migrants has had the perverse effect of providing a safety-valve for disaffected parts of the population even as it saps Cuba demographically.

By comparison, despite the long history of coups and corruption prior to Chávez, and a popular-democratic constitution under his rule, the Venezuelan state never underwent the same kind of revolutionary remaking. Despite Chávez’s enlistment of Cuban support in restructuring parts of the military and intelligence services, the chavista transformations were of more limited scope. It is likely that this has made for more openings for US intelligence people to gain toeholds or find potential traitors with whom to negotiate. It is hard to imagine this being equally true of Cuba. No doubt the spooks have been studying the terrain carefully to see where they might work their magic, but the mechanisms set up precisely to prevent such a thing may still have some life left in them. The example recently made of Alejandro Gil Fernández, Economy Minister until his downfall in 2024 – convicted of espionage along with corruption, embezzlement, bribery, tax evasion and money laundering – may be a sign of that, although the potpourri of allegations and the opacity of the process suggest that one should not take the official line at face value. Rumours have circulated about cases of high-level corruption and co-optation by foreign intelligence, but it is hard to know what to credit. The greatest danger is here. Revolutionary states do not persist unchanged over time, and their mutations are often linked to the loss of their founders. As the revolutionary cohort passes, Cuba is in uncharted waters. Will its old antagonist finally find suitable collaborators, or will its latest aggressions rally new generations?

Read on: Ernesto Teuma, ‘A New Left in Cuba’, NLR 150.

.

We remind our readers that publication of articles on our site does not mean that we agree with what is written. Our policy is to publish anything which we consider of interest, so as to assist our readers in forming their opinions. Sometimes we even publish articles with which we totally disagree, since we believe it is important for our readers to be informed on as wide a spectrum of views as possible.